Learning Objectives

- Explain why Congress amended the U.S. Constitution to reduce the period of time between presidential elections and inaugurations

The Interregnum

After the landslide election, the country—and Hoover—had to endure the interregnum, the difficult four months between the election and President Roosevelt’s inauguration in March 1933. During this period, Hoover became what pundits called a “lame duck,” retaining his office for a short time while losing any remaining mandate to govern. Unsurprisingly, Congress did not pass a single significant piece of legislation during this period. However, Hoover spent much of the time trying to get Roosevelt to commit publicly to a legislative agenda of Hoover’s choosing. Roosevelt remained gracious but refused to begin his administration as the incumbent’s advisor without legal authority to change policy. Unwilling to tie himself to Hoover’s legacy of failed policies, Roosevelt kept quiet when Hoover supported the passage of a national sales tax.

Meanwhile, the country suffered from Hoover’s inability to drive a legislative agenda through Congress further. It was the worst winter since the beginning of the Great Depression, and the banking sector again suffered another round of panic. While Roosevelt kept his distance from the final tremors of the Hoover administration, the country continued to suffer in wait. In response to the challenges of this time, the U.S. Constitution was subsequently amended to reduce the period from election to inauguration to the now-commonplace two months.

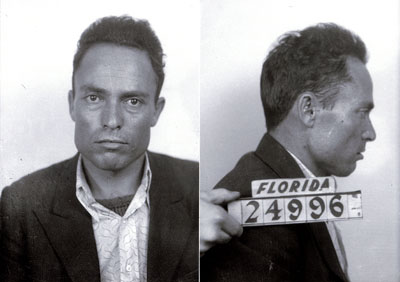

The Assassination Attempt

Roosevelt’s ideas almost did not come to fruition, thanks to a would-be assassin’s bullet. On February 15, 1933, after delivering a speech from his open car in Miami’s Bayfront Park, local Italian bricklayer Giuseppe Zangara emerged from a crowd of well-wishers to fire six shots from his revolver. Although Roosevelt emerged from the assassination attempt unscathed, Zangara wounded five individuals that day, including Chicago Mayor Tony Cermak, who attended the speech in the hopes of resolving any long-standing differences with the president-elect. Roosevelt and his driver immediately rushed Cermak to the hospital, where he died three days later. Roosevelt’s calm and collected response to the event reassured many Americans of his ability to lead the nation through the challenges they faced. All that awaited was Roosevelt’s inauguration before his ideas would unfold to the expectant public.

Roosevelt’s Plan for the Economy

So what was Roosevelt’s plan? Before he took office, it seems likely that he was not entirely sure. Certain elements were known: He believed in positive government action to solve the Depression; he believed in federal relief, public works, social security, and unemployment insurance; he wanted to restore public confidence in banks; he wanted stronger government regulation of the economy; he wanted to help farmers directly. But how to take action on these beliefs was more in question. A month before his inauguration, he said to his advisors, “Let’s concentrate upon one thing: Save the people and the nation, and if we have to change our minds twice every day to accomplish that end, we should do it.”

“Let’s concentrate upon one thing: Save the people and the nation, and if we have to change our minds twice every day to accomplish that end, we should do it.”

The “Brains Trust”

Unlike Hoover, who professed an ideology of “American individualism,” an adherence that rendered him largely incapable of widespread action, Roosevelt remained pragmatic and open-minded to possible solutions. To assist in formulating various relief and recovery programs, Roosevelt turned to a group of men who had previously orchestrated his election campaign and victory. Collectively known as the “Brains Trust” (a phrase coined by a New York Times reporter to describe the multiple “brains” on Roosevelt’s advisory team), the group most notably included Rexford Tugwell, Raymond Moley, and Adolph Berle. Moley, credited with bringing the group into existence, was a government professor who advocated for a new national tax policy to help the nation recover from its economic woes. Tugwell, who eventually focused his energy on the country’s agricultural problems, saw an increased role for the federal government in setting wages and prices across the economy. Berle was a mediating influence, who often advised against a centrally controlled economy, but did see the role that the federal government could play in mediating the stark cycles of prosperity and depression that, if left unchecked, could result in the very situation in which the country presently found itself.

Together, these men and others advised Roosevelt through the earliest days of the New Deal and helped craft effective legislative programs for congressional review and approval.

Try It

Inauguration Day: A New Beginning

March 4, 1933, dawned gray and rainy. Roosevelt rode in an open car with outgoing president Hoover, facing the public, as he made his way to the U.S. Capitol. Hoover’s mood was somber, still personally angry over his defeat in the general election the previous November; he refused to crack a smile during the ride among the crowd, despite Roosevelt’s urging to the contrary. At the ceremony, Roosevelt rose with the aid of leg braces equipped under his specially tailored trousers and placed his hand on a Dutch family Bible as he took his solemn oath.

Figure 2. Roosevelt’s inauguration was indeed a day of new beginnings for the country. The sun breaking through the clouds as he was sworn in became a metaphor for the hope people felt at his presidency.

Bathed in the sunlight, Roosevelt delivered one of the most famous and oft-quoted inaugural addresses in history. He encouraged Americans to work with him to solve the nation’s problems and not to be paralyzed by fear into inaction. Borrowing a wartime analogy provided by Moley, who served as his speechwriter, Roosevelt called upon all Americans to assemble and fight an essential battle against the forces of economic depression. He famously stated, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” and “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”[1] Upon hearing his inaugural address, one observer in the crowd later commented, “Any man who can talk like that in times like these is worth every ounce of support a true American has.” To borrow the famous song title of the day, “happy days were here again.” Foregoing the traditional inaugural parties, the new president immediately returned to the White House to begin his work to save the nation.

Try It

Watch It

On March 4, 1933, in his first inaugural address, Roosevelt famously declared, “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

Review Questions

- What was the purpose of Roosevelt’s “Brains Trust?”

Show Answer

- Compare and contrast Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt’s approaches to fixing the American economy. How did their approaches affect their popularity with the American people and their effectiveness in office?

Show Answer

Glossary

Brains Trust: an unofficial advisory cabinet to President Franklin Roosevelt, gathered initially while he was governor of New York to present possible solutions to the nations’ problems; among its prominent members were Rexford Tugwell, Raymond Moley, and Adolph Berle

interregnum: the period between the election and the inauguration of a new president; when economic conditions worsened significantly during the four-month lag between Roosevelt’s win and his move into the Oval Office, Congress amended the Constitution to limit this period to two months

lame duck: This term refers to an incumbent who has been voted out of office, but must stay in power until the inauguration of their successor. The phrase alludes to the political powerlessness the incumbent has. (Because of the ableist connotations of “lame duck,” the term is not in common usage today.)

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Kaitlyn Connell for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- The Great Depression. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/23-the-great-depression/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Inauguration (March 4, 1933). Provided by: C-SPAN. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HRylj-_HBAw. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Giuseppe Zangara mugshot. Provided by: Florida Department of Corrections. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giuseppe_Zangara_mugshot.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1933. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=14473. ↵