Learning Objectives

- Explain the growth of American cities in the late nineteenth century

Changes Outside the Workplace

Industrialization also remade much of American life outside the workplace. Rapidly growing industrialized cities knit together urban consumers and rural producers into a single, integrated national market. Food production and consumption, for instance, became national in scope. Chicago’s stockyards seemingly tied it all together. Between 1866 and 1886, ranchers drove a million head of cattle annually overland from Texas ranches to railroad depots in Kansas for shipment by rail to Chicago. After traveling through modern “disassembly lines,” the animals left the adjoining slaughterhouses as slabs of meat to be packed into refrigerated rail cars and sent to butcher shops across the continent. By 1885, a handful of large-scale industrial meatpackers in Chicago were producing nearly five hundred million pounds of “dressed” beef annually.[1] The new scale of industrialized meat production transformed the landscape. Buffalo herds, grasslands, and old-growth forests gave way to cattle, corn, and wheat. Chicago became the Gateway City, a crossroads connecting American agricultural goods, capital markets in New York and London, and consumers from all corners of the United States.

Technological innovation accompanied economic development. For April Fool’s Day in 1878, the New York Daily Graphic published a fictitious interview with the celebrated inventor Thomas A. Edison. The piece described the “biggest invention of the age”—a new Edison machine that could create forty different kinds of food and drink out of only air, water, and dirt. “Meat will no longer be killed and vegetables no longer grown, except by savages,” Edison promised. The machine would end “famine and pauperism.” And all for $5 or $6 per machine! The story was a joke, of course, but Edison nevertheless received inquiries from readers wondering when the food machine would be ready for the market. Americans had apparently witnessed such startling technological advances—advances that would have seemed far-fetched mere years earlier—that the Edison food machine seemed entirely plausible.[2]

The Effects of Urbanization

Urbanization occurred rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States for a number of reasons. The new technologies of the time led to a massive leap in industrialization, requiring large numbers of workers. New electric lights and powerful machinery allowed factories to run twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Workers were forced into grueling twelve-hour shifts, requiring them to live close to the factories.

While the work was dangerous and difficult, many Americans were willing to leave behind the declining prospects of preindustrial agriculture in the hope of better wages in industrial labor. Furthermore, problems ranging from famine to religious persecution led a new wave of immigrants to arrive from central, eastern, and southern Europe, many of whom had no choice but to settle in the coastal cities where they arrived because they could not afford to travel farther inland. Immigrants sought solace and comfort among others who shared the same language and customs, and the nation’s cities became an invaluable economic and cultural resource.

Although cities such as Philadelphia, Boston, and New York sprang up from the initial days of colonial settlement, the explosion in urban population growth did not occur until the mid-nineteenth century. At this time, the attractions of city life, and in particular, employment opportunities, grew exponentially due to rapid changes in industrialization. Before the mid-1800s, factories, such as the early textile mills, had to be located near rivers and seaports, both for the transport of goods and the necessary water power. Production became dependent upon seasonal water flow, with cold, icy winters all but stopping river transportation entirely. The development of the steam engine and the advent of mass-market electricity transformed this need, allowing businesses to locate their factories near urban centers. These factories encouraged more and more people to move to urban areas where jobs were plentiful, but hourly wages were often low and the work was routine and grindingly monotonous.

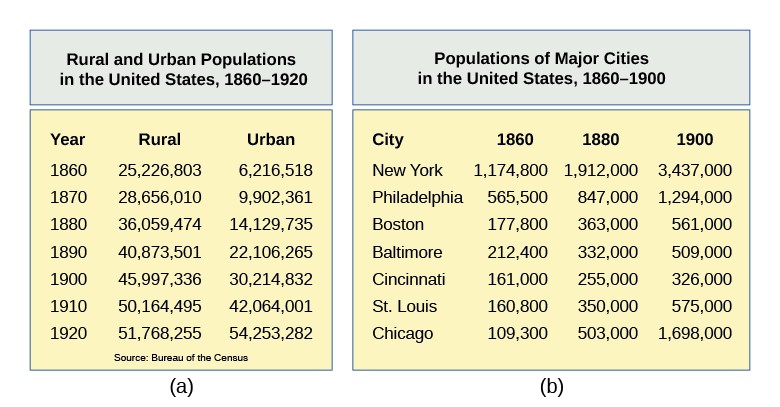

Figure 1. As these panels illustrate, the population of the United States grew rapidly in the late 1800s (a). Much of this new growth took place in urban areas (defined by the census as twenty-five hundred people or more), and this urban population, particularly that of major cities (b), dealt with challenges and opportunities that were unknown in previous generations.

Interactive

Click through each of the slides in this interactive to learn more about population growth and change during the nineteenth century.

Eventually, cities developed their own unique characters based on the core industry that spurred their growth. In Pittsburgh, it was steel; in Chicago, it was meat packing; in New York, the garment and financial industries dominated; and Detroit, by the mid-twentieth century, was defined by the automobiles it built. But all cities at this time, regardless of their industry, suffered from the universal problems that rapid expansion brought with it, including concerns over housing and living conditions, transportation, and communication. These issues were almost always rooted in deep class inequalities, shaped by racial divisions, religious differences, and ethnic strife, and distorted by corrupt local politics.

Link to Learning

This 1884 Bureau of Labor Statistics report from Boston looks in detail at the wages, living conditions, and moral code of the girls who worked in the clothing factories there.

Rural Decline & the Rise of Suburbia

While cities boomed, rural worlds languished. For a population that took pride in its Protestant character and pioneer spirit, the turn toward dense industrial cities teeming with immigrants was a seismic, and troubling, change. Sociologist Kenyon Butterfield, concerned by the sprawling nature of industrial cities and suburbs, regretted the eroding social position of rural citizens and farmers: “Agriculture does not hold the same relative rank among our industries that it did in former years.”[3] He and many others thought the rise of the cities and the fall of the countryside threatened traditional American values. Liberty Hyde Bailey, a botanist and rural scholar, feared that cities were becoming corrupt and impersonal. At the same time, he feared that rural areas, where he saw traditional values and the democratic spirit thriving, were becoming depopulated. Bailey’s Country Life Movement wished to reinvigorate the rural family farm with scientific methods and new technology. In this way, rural areas could better provide for cities, and rural culture and habits would improve the character of city life. “ Every agricultural question is a city question,” Bailey concluded, recognizing how the two were intractably linked.[4]

Many longed for a middle path, with the amenities and cosmopolitan nature of cities, but with the wholesome and bucolic atmosphere of the countryside. New suburban communities on the outskirts of American cities grew to meet this desire. Los Angeles became a model for the suburban development of rural places. Dana Barlett, a social reformer in Los Angeles, noted that the city, stretching across dozens of small towns, was “a better city” because of its residential identity as a “city of homes.” rather than crowded and unsanitary tenements. This language was seized upon by many suburbs that hoped to avoid both urban sprawl and rural decay. In Glendora, one of these small towns on the outskirts of Los Angeles, local leaders were “loath as anyone to see it become cosmopolitan.” Instead, in order to have Glendora “grow along the lines necessary to have it remain an enjoyable city of homes,” they needed to “bestir ourselves to direct its growth” by encouraging not industry or agriculture but residential development.

The Keys to Successful Urbanization

As the country grew, certain elements led some towns to morph into large urban centers, while others did not. The following four innovations proved critical in shaping urbanization at the turn of the century: electric lighting, communication improvements, intracity transportation, and the rise of skyscrapers. As people migrated for new jobs, they often struggled with the absence of basic urban infrastructures, such as better transportation, adequate housing, means of communication, and efficient sources of light and energy. Even the basic necessities, such as fresh water and proper sanitation—often taken for granted in the countryside—presented a greater challenge in urban life.

Electric Lighting

Thomas Edison patented the incandescent light bulb in 1879. This development quickly became common in homes as well as factories, transforming how even lower- and middle-class Americans lived. Although slow to arrive in rural areas of the country, electric power became readily available in cities when the first commercial power plants began to open in 1882. When Nikola Tesla subsequently developed the AC (alternating current) system for the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company, power supplies for lights and other factory equipment could extend for miles from the power source. AC power transformed the use of electricity, allowing urban centers to physically cover greater areas. In the factories, electric lights permitted operations to run twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. This increase in production required additional workers, and this demand brought more people to cities.

Gradually, cities began to illuminate the streets with electric lamps around the clock. No longer did the pace of life and economic activity slow substantially at sunset, the way it had in smaller towns. The cities, following the factories that drew people there, stayed open all the time.

Communications Improvements

The telephone, patented in 1876, greatly transformed communication both regionally and nationally. The telephone rapidly supplanted the telegraph as the preferred form of communication; by 1900, over 1.5 million telephones were in use around the nation, whether as private lines in the homes of some middle- and upper-class Americans, or jointly used “party lines” in many rural areas. By allowing instant communication over larger distances at any given time, growing telephone networks made urban sprawl possible.

Figure 2. An early Omnibus design from London, c. 1829.

In the same way that electric lights spurred greater factory production and economic growth, the telephone increased business through the more rapid pace of demand. Now, orders could come constantly via telephone, rather than via mail-order. More orders generated greater production, which in turn required still more workers. Business owners could also communicate directly with their bankers, stockbrokers, and other financial experts to determine how new economic situations would affect them and then implement solutions in real-time. This demand for additional labor and rapid relay of information played a key role in urban growth, as expanding companies sought workers to handle the increasing consumer demand for their products.

Intracity Transportation

As cities grew and sprawled outward, a major challenge was efficient travel within the city—from home to factories or shops, and then back again. Most transportation infrastructure was used to connect cities to each other, typically by rail or canal. Prior to the 1880s, the most common form of transportation within cities was the omnibus. This was a large, horse-drawn carriage, often placed on iron or steel tracks to provide a smoother ride. While omnibuses worked adequately in smaller, less congested cities, they were not equipped to handle the larger crowds that developed at the close of the century. The horses had to stop and rest, and horse manure became an ongoing problem.

Figure 3. Although trolleys were far more efficient than horse-drawn carriages, populous cities such as New York experienced frequent accidents, as depicted in this 1895 illustration from Leslie’s Weekly (a). To avoid overcrowded streets, trolleys soon went underground, as at the Public Gardens Portal in Boston (b), where three different lines met to enter the Tremont Street Subway, the oldest subway tunnel in the United States, opening on September 1, 1897.

In 1887, Frank Sprague invented the electric trolley, which worked in a similar fashion as the omnibus, with a large wagon on tracks, but was powered by electricity rather than horses. The electric trolley could run throughout the day and night, like the factories and the workers who fueled them. But it also modernized less important industrial centers, such as the southern city of Richmond, Virginia. As early as 1873, San Francisco engineers adopted pulley technology from the mining industry to introduce cable cars and turn the city’s steep hills into elegant middle-class communities.

Figure 4. While the technology existed to engineer tall buildings, it was not until the invention of the electric elevator in 1889 that skyscrapers began to take over the urban landscape. Shown here is the Home Insurance Building in Chicago, considered the first modern skyscraper.

However, as crowds continued to grow in the largest cities, such as Chicago and New York, trolleys were unable to move efficiently through the crowds of pedestrians. To avoid this challenge, city planners elevated the trolley lines above the streets, creating elevated trains, or L-trains, as early as 1868 in New York City, and quickly spreading to Boston in 1887 and Chicago in 1892. Finally, as skyscrapers began to dominate the air, transportation evolved one step further to move underground as subways. Boston’s subway system began operating in 1897, and was quickly followed by New York and other cities.

The Rise of Skyscrapers

The last limitation that large cities had to overcome was the ever-increasing need for space. Eastern cities, unlike their midwestern counterparts, could not continue to grow outward, as the land surrounding them was already settled. Geographic limitations such as rivers or the coast also hampered sprawl. And in all cities, citizens needed to be close enough to urban centers to conveniently access work, shops, and other core institutions of urban life. The increasing cost of real estate made upward growth attractive, and so did the prestige that towering buildings carried for the businesses that occupied them. Workers completed the first skyscraper in Chicago, the ten-story Home Insurance Building, in 1885. Although engineers had the capability to go higher, thanks to new steel construction techniques, they required another vital invention in order to make taller buildings viable: the elevator. In 1889, the Otis Elevator Company, led by inventor James Otis, installed the first electric elevator. This began the skyscraper craze, allowing developers in eastern cities to build and market prestigious real estate in the hearts of crowded eastern metropoles.

Economic advances, technological innovation, social and cultural evolution, demographic changes: the United States was a nation transformed. Industry boosted productivity, railroads connected the nation, more and more Americans labored for wages, new bureaucratic occupations created a vast “white-collar” middle class, and unprecedented fortunes rewarded the owners of capital. These revolutionary changes, of course, would not occur without conflict or consequence, but they demonstrated the profound transformations remaking the nation. The changes were not confined to economics alone, but also gripped the lives of everyday Americans and fundamentally reshaped American culture.[5]

Try It

Review Question

Glossary

electric trolley: invented to replace the omnibus, which was inefficient and messy due to the use of horses; the electric trolley could move faster and was cleaner, but also had problems moving in the crowded urban streets; eventually they were placed on elevated tracks, then moved underground as subways

omnibus: a horse-drawn trolley that sometimes sat on rails; used for urban transportation before the invention of the electric trolley

Otis Elevator Company: the first company to create an electric elevator, allowing for the construction of even taller skyscrapers in urban areas

suburb: a “middle way” between rural living and urban living that allowed people to live outside of the city, but close enough to amenities that they were not rural; suburbs began to grow in the 19th century with the increase in railroads, public transportation, and improved roads because they allowed people to commute to work

Candela Citations

- Population growth interactive. Authored by: Erica Holland for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Life in Industrial America. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/18-industrial-america/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Omnibus. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shillibeer%27s_first_omnibus.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 239. ↵

- David Hochfelder, “Edison and the Age of Invention,” in A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865–1881, ed. Edward O. Frantz (Chichester, UK: Blackwell, 2014), 499. ↵

- Kenyon L. Butterfield, Chapters in Rural Progress (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1908), 15. ↵

- L. H. Bailey, The Harvest of the Year to the Tiller of the Soil (New York: Macmillan, 1927), 60. ↵

- Ibid., 499–517. ↵