Learning Outcomes

- Identify the factors that prompted European immigration to American cities in the late nineteenth century

- Discuss the demographic and cultural shifts in the U.S. population during the late nineteenth century

As industrial growth continued, the manufacturing sector needed the workers and the infrastructure that would sustain them. This change was transformative; America’s urban population increased sevenfold in the half-century after the Civil War. Soon the United States had more large cities than any country in the world. The 1920 U.S. census revealed that, for the first time, a majority of Americans lived in urban areas. Much of that urban growth came from the millions of immigrants pouring into the nation. Between 1870 and 1920, over twenty-five million immigrants arrived in the United States.

Immigrating to America

Push & Pull Factors

By the turn of the twentieth century, new immigrant groups such as Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made up a larger percentage of arrivals than the Irish and Germans. The specific reasons that immigrants left their particular countries and the reasons they came to the United States, what historians call push factors and pull factors, varied. For example, a young husband and wife living in Sweden in the 1880s and unable to purchase farmland might read an advertisement for inexpensive land in the American Midwest and immigrate to the United States to begin a new life. A young Italian man might simply hope to labor in a steel factory long enough to save up enough money to return home and purchase land for his family. A Jewish family facing persecution in Russian pogroms might look to the United States as a sanctuary. Or perhaps a Japanese migrant might hear of fertile farming land on the West Coast and choose to sail for California. But if many factors pushed people away from their home countries, by far the most important factor drawing immigrants was economics. Immigrants came to the United States looking for work and new economic opportunities.

Industrial capitalism was the most important factor that drew immigrants to the United States between 1880 and 1920. Immigrant workers labored in large industrial complexes producing goods such as steel, textiles, and food products, replacing smaller and more local workshops. The influx of immigrants, alongside a large movement of Americans from the countryside to the city, helped propel the rapid growth of cities like New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. By 1890, immigrants and their children accounted for roughly 60 percent of the population in most large northern cities (and sometimes as high as 80 or 90 percent). Many immigrants, especially from Italy and the Balkans, had intended to return home with enough money to purchase land. But what about those who stayed? Did the new arrivals assimilate together in the American melting pot—becoming just like those already in the United States—or did they retain, and sometimes even strengthen, their traditional ethnic identities? The answer lies somewhere in between.

Figure 1. The “mosaic” theory of immigration & assimilation states that each cultural group maintains some distinct traits and practices, but that they all come together to make up a bigger picture.

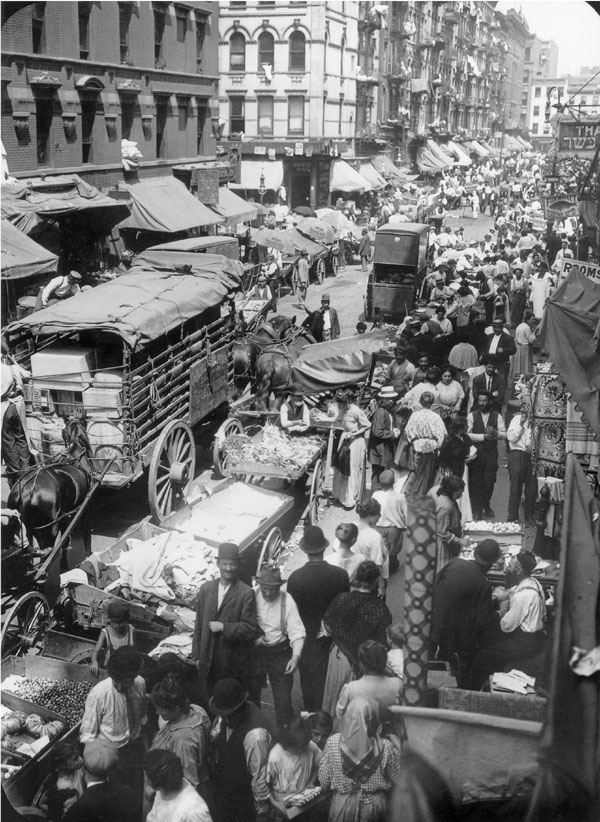

Immigrants from specific countries—and sometimes even specific communities—often clustered together in the same neighborhoods, called ethnic enclaves. They formed vibrant organizations and societies, such as Italian workmen’s clubs, Eastern European Jewish mutual aid societies, and Polish Catholic churches, to ease the transition to their new American home. Immigrant communities published newspapers in dozens of languages and purchased spaces to keep their arts, languages, and traditions alive. And from these foundations they facilitated even more immigration: after staking out a claim to some corner of American life, they wrote home and encouraged others to follow them, a phenomenon called chain migration.

Figure 2. Part of Little Italy, New York (“Hester Street, New York City” By an unknown photographer) ca. 1903. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Public Housing Administration.

Some historians, therefore, suggest the metaphor of a “mosaic” rather than a “melting pot,” where national communities remained fairly distinct and maintained the unique traits of their culture of origin.

Adjusting to American Life

While most immigrants who arrived in the United States were hopeful about their prospects in this rapidly expanding nation, not all of them arrived on an equal footing. Those coming from poor or rural backgrounds, especially in Eastern Europe, were less likely to be able to read or speak English, making their transition to life in America harder. They had to rely on others for help getting settled, including finding work and a place to live, and they were often taken advantage of by “agents” who would force them to sign exploitive labor contracts or who would take a fee and then disappear. Even those who arrived speaking English, like the Irish, were at risk for maltreatment simply because they had few resources.

Certain characteristics or skills, called assets, might make life for an immigrant easier in America. Assets included things like the ability to speak English, having a skilled trade or formal education, or having money saved up. Assets could even be things like race and religion that would make them fit in with American society better. An immigrant who was white and Protestant would have an easier time after immigrating to the U.S. than an immigrant who was non-white or non-Protestant. The characteristics that could make the transition more difficult for immigrants, called liabilities, were things like not knowing English, coming from a poor background, or not having a formal education or trade. These assets & liabilities affected all areas of immigrant life, including which jobs they got and where they lived. For example, immigrants who did not have a skilled trade were usually recruited right off the boats to work in factories and might be given housing in a company-owned tenement building. An immigrant who had a skilled trade, like being a butcher, a carpenter, a doctor, or a blacksmith, might be able to move beyond the city and settle in a small town or more rural area. Particularly in the West, which was still being settled, immigrants with skills were needed to help new towns thrive. The places where immigrants moved to and the reasons they moved are referred to as settlement patterns, because they were fairly predictable based on where someone immigrated from and what types of skills they brought with them.

Try It

The Changing Nature of European Immigration

Immigrants drastically shifted the demographics of many rapidly growing cities. Although immigration had always been a force of change in the United States, it took on a new character in the late nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1880s, the arrival of immigrants from mostly southern and eastern European countries rapidly increased while the flow from northern and western Europe remained relatively constant.

| Region Country | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern and Western Europe | 4,845,679 | 5,499,889 | 7,288,917 | 7,204,649 | 7,306,325 |

| Germany | 1,690,533 | 1,966,742 | 2,784,894 | 2,663,418 | 2,311,237 |

| Ireland | 1,855,827 | 1,854,571 | 1,871,509 | 1,615,459 | 1,352,251 |

| England | 550,924 | 662,676 | 908,141 | 840,513 | 877,719 |

| Sweden | 97,332 | 194,337 | 478,041 | 582,014 | 665,207 |

| Austria | 30,508 | 38,663 | 123,271 | 275,907 | 626,341 |

| Norway | 114,246 | 181,729 | 322,665 | 336,388 | 403,877 |

| Scotland | 140,835 | 170,136 | 242,231 | 233,524 | 261,076 |

| Southern and Eastern Europe | 93,824 | 248,620 | 728,851 | 1,674,648 | 4,500,932 |

| Italy | 17,157 | 44,230 | 182,580 | 484,027 | 1,343,125 |

| Russia | 4,644 | 35,722 | 182,644 | 423,726 | 1,184,412 |

| Poland | 14,436 | 48,557 | 147,440 | 383,407 | 937,884 |

| Hungary | 3,737 | 11,526 | 62,435 | 145,714 | 495,609 |

| Czechoslovakia | 40,289 | 85,361 | 118,106 | 156,891 | 219,214 |

The previous waves of immigrants from northern and western Europe, particularly Germany, Great Britain, and the Nordic countries, were relatively well off, arriving in the country with some funds and often moving to the newly settled western territories. In contrast, the newer immigrants from southern and eastern European countries, including Italy, Greece, and several Slavic countries including Russia, came to America due to push and pull factors similar to those that influenced the African-Americans arriving from the South. Many were “pushed” from their countries by a series of ongoing famines, by religious, political, and racial persecution, or by the desire to avoid compulsory military service. They were also “pulled” by the promise of consistent, wage-earning work.

Whatever the reason, these immigrants arrived without the education and finances of the earlier waves of immigrants and settled more readily in the port towns. By 1890, over 80 percent of the population of New York would be either foreign-born or children of foreign-born parentage. Other cities saw huge spikes in foreign populations as well, though not to the same degree, due in large part to Ellis Island in New York City being the primary port of entry for most European immigrants arriving in the United States.

iNteractive

Click through each of the slides in the interactive below to learn more accelerating immigration during the last part of the twentieth century.

Ellis Island

The number of immigrants peaked between 1900 and 1910, when over nine million people arrived in the United States. To assist in the processing and management of this massive wave of immigrants, the Bureau of Immigration in New York City, which had become the official port of entry, opened Ellis Island in 1892. Today, nearly half of all Americans have ancestors who, at some point in time, entered the country through the portal at Ellis Island. Doctors or nurses inspected the immigrants upon arrival, looking for any signs of infectious diseases. Most immigrants were admitted to the country with only a cursory glance at any other paperwork. Roughly 2 percent of the arriving immigrants were denied entry due to a medical condition or criminal history. The rest would enter the country by way of the streets of New York, many unable to speak English and totally reliant on finding those who spoke their native tongue.

Figure 3. This photo shows newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island in New York. Inspectors are examining them for contagious health problems, which could require them to be sent back. (credit: NIAID)

Seeking comfort in a strange land, as well as a common language, many immigrants sought out relatives, friends, former neighbors, townspeople, and countrymen who had already settled in American cities. This led to a rise in ethnic enclaves within the larger cities. Little Italy, Chinatown, and many other communities developed in which immigrant groups could find everything to remind them of home, from local language newspapers to ethnic food stores. While these enclaves provided a sense of community to their members, they added to the problems of urban congestion, particularly in the poorest slums which were the only places where many immigrants could afford housing.

Backlash and Discrimination

Link to Learning

The global timeline of immigration at the Library of Congress offers a summary of immigration policies and the groups affected by it, as well as a compelling overview of different ethnic groups’ immigration stories. Browse through to see how different ethnic groups made their way in the United States.

This Library of Congress exhibit on the history of Jewish immigration to the United States illustrates the ongoing challenge immigrants felt between the ties to their old land and a love for America.

Growing numbers of Americans resented the waves of new immigrants, resulting in a backlash. The Reverend Josiah Strong fueled the hatred and discrimination in his bestselling book, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis, published in 1885. In a revised edition that reflected the 1890 census records, he clearly identified “undesirable” immigrants—those from southern and eastern European countries—as a key threat to the moral fiber of the country, and urged all good Americans to face the challenge. Several thousand Americans answered his call by forming the American Protective Association, the chief political activist group to promote legislation curbing immigration into the United States. The group successfully lobbied Congress to adopt both an English language literacy test for immigrants, which eventually passed in 1917, and the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned nearly all immigration from China after 1882. The group’s political lobbying also laid the groundwork for the subsequent Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, as well as the National Origins Act, all of which sought to clamp what was seen as unchecked flooding of immigration into American cities.

Review Question

What made recent European immigrants the ready targets of more established city dwellers? What was the result of this discrimination?

Watch it

This video details the major increases in immigration to the United States during the late 19th and early 20th century, as well as the reactions and responses to the changes in the population.

You can view the transcript for “Growth, Cities, and Immigration: Crash Course US History #25” here (opens in new window).

Try It

Glossary

American Protective Association: an organization created to “protect” American society, government, and culture from the threat that they believed immigrants posed

assets & liabilities: characteristics of immigrants that make their lives easier (assets) or harder (liabilities) in a new country; examples include native language, skills or education, race, religion, and socio-economic status

chain migration: a phenomenon where one group of immigrants tells people in their home country about the opportunities they have found, prompting their friends or family members to also immigrate

Dillingham Commission: a Congressional commission created in 1907 to report on immigration numbers and demographics

Ellis Island: the immigration processing center in New York Harbor that processed the vast majority of European immigrants to the U.S. between 1892 and 1954

ethnic enclaves: neighborhoods or towns where large numbers of immigrants from a specific country or region gathered and lived together, opening up businesses that catered to other immigrants, speaking their native language freely, and practicing their cultural traditions

push and pull factors: events or conditions that “push” immigrants out of their home country and “pull” them to a new country; examples of push factors include war, famine, persecution, and economic troubles; examples of pull factors include religious freedom/tolerance, availability of land or jobs, and a booming economy

settlement patterns: the pattern of places where immigrants settle or are likely to settle based on their country of origin, skills, job, etc

xenophobia: a hatred for or prejudice against people from another country, no matter their language, religion, or race

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Mark Lempke and Lillian Wills for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Immigration Interactive. Authored by: Erica Holland for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Life in Industrial America. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/18-industrial-america/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mosaic. Authored by: Tim Mossholder. Provided by: Pexels. Located at: https://www.pexels.com/photo/multicolored-mosaic-photo-936802/. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Growth, Cities, and Immigration: Crash Course US History #25. Provided by: Crash Course. Located at: https://youtu.be/RRhjqqe750A?t=1s. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Little Italy New York. Provided by: Archives. Located at: https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/picturing_the_century/newcent/newcent_img3.html. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright