Experimental Research

As you’ve learned, the only way to establish that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables is to conduct a scientific experiment. Experiment has a different meaning in the scientific context than in everyday life. In everyday conversation, we often use it to describe trying something for the first time, such as experimenting with a new hairstyle or new food. However, in the scientific context, an experiment has precise requirements for design and implementation.

Video 2.8.1. Experimental Research Design provides explanation and examples for correlational research. A closed-captioned version of this video is available here.

The Experimental Hypothesis

In order to conduct an experiment, a researcher must have a specific hypothesis to be tested. As you’ve learned, hypotheses can be formulated either through direct observation of the real world or after careful review of previous research. For example, if you think that children should not be allowed to watch violent programming on television because doing so would cause them to behave more violently, then you have basically formulated a hypothesis—namely, that watching violent television programs causes children to behave more violently. How might you have arrived at this particular hypothesis? You may have younger relatives who watch cartoons featuring characters using martial arts to save the world from evildoers, with an impressive array of punching, kicking, and defensive postures. You notice that after watching these programs for a while, your young relatives mimic the fighting behavior of the characters portrayed in the cartoon. Seeing behavior like this right after a child watches violent television programming might lead you to hypothesize that viewing violent television programming leads to an increase in the display of violent behaviors. These sorts of personal observations are what often lead us to formulate a specific hypothesis, but we cannot use limited personal observations and anecdotal evidence to test our hypothesis rigorously. Instead, to find out if real-world data supports our hypothesis, we have to conduct an experiment.

Designing an Experiment

The most basic experimental design involves two groups: the experimental group and the control group. The two groups are designed to be the same except for one difference— experimental manipulation. The experimental group gets the experimental manipulation—that is, the treatment or variable being tested (in this case, violent TV images)—and the control group does not. Since experimental manipulation is the only difference between the experimental and control groups, we can be sure that any differences between the two are due to experimental manipulation rather than chance.

In our example of how violent television programming might affect violent behavior in children, we have the experimental group view violent television programming for a specified time and then measure their violent behavior. We measure the violent behavior in our control group after they watch nonviolent television programming for the same amount of time. It is important for the control group to be treated similarly to the experimental group, with the exception that the control group does not receive the experimental manipulation. Therefore, we have the control group watch non-violent television programming for the same amount of time as the experimental group.

We also need to define precisely, or operationalize, what is considered violent and nonviolent. An operational definition is a description of how we will measure our variables, and it is important in allowing others to understand exactly how and what a researcher measures in a particular experiment. In operationalizing violent behavior, we might choose to count only physical acts like kicking or punching as instances of this behavior, or we also may choose to include angry verbal exchanges. Whatever we determine, it is important that we operationalize violent behavior in such a way that anyone who hears about our study for the first time knows exactly what we mean by violence. This aids peoples’ ability to interpret our data as well as their capacity to repeat our experiment should they choose to do so.

Once we have operationalized what is considered violent television programming and what is considered violent behavior from our experiment participants, we need to establish how we will run our experiment. In this case, we might have participants watch a 30-minute television program (either violent or nonviolent, depending on their group membership) before sending them out to a playground for an hour where their behavior is observed and the number and type of violent acts are recorded.

Ideally, the people who observe and record the children’s behavior are unaware of who was assigned to the experimental or control group, in order to control for experimenter bias. Experimenter bias refers to the possibility that a researcher’s expectations might skew the results of the study. Remember, conducting an experiment requires a lot of planning, and the people involved in the research project have a vested interest in supporting their hypotheses. If the observers knew which child was in which group, it might influence how much attention they paid to each child’s behavior as well as how they interpreted that behavior. By being blind to which child is in which group, we protect against those biases. This situation is a single-blind study, meaning that the participants are unaware as to which group they are in (experiment or control group) while the researcher knows which participants are in each group.

In a double-blind study, both the researchers and the participants are blind to group assignments. Why would a researcher want to run a study where no one knows who is in which group? Because by doing so, we can control for both experimenter and participant expectations. If you are familiar with the phrase placebo effect, you already have some idea as to why this is an important consideration. The placebo effect occurs when people’s expectations or beliefs influence or determine their experience in a given situation. In other words, simply expecting something to happen can actually make it happen.

The placebo effect is commonly described in terms of testing the effectiveness of a new medication. Imagine that you work in a pharmaceutical company, and you think you have a new drug that is effective in treating depression. To demonstrate that your medication is effective, you run an experiment with two groups: The experimental group receives the medication, and the control group does not. But you don’t want participants to know whether they received the drug or not.

The placebo effect is commonly described in terms of testing the effectiveness of a new medication. Imagine that you work in a pharmaceutical company, and you think you have a new drug that is effective in treating depression. To demonstrate that your medication is effective, you run an experiment with two groups: The experimental group receives the medication, and the control group does not. But you don’t want participants to know whether they received the drug or not.

Why is that? Imagine that you are a participant in this study, and you have just taken a pill that you think will improve your mood. Because you expect the pill to have an effect, you might feel better simply because you took the pill and not because of any drug actually contained in the pill—this is the placebo effect.

To make sure that any effects on mood are due to the drug and not due to expectations, the control group receives a placebo (in this case, a sugar pill). Now everyone gets a pill, and once again, neither the researcher nor the experimental participants know who got the drug and who got the sugar pill. Any differences in mood between the experimental and control groups can now be attributed to the drug itself rather than to experimenter bias or participant expectations.

Video 2.8.2. Introduction to Experimental Design introduces fundamental elements for experimental research design.

Independent and Dependent Variables

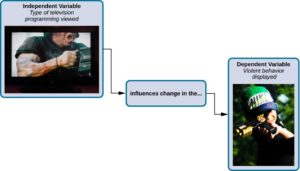

In a research experiment, we strive to study whether changes in one thing cause changes in another. To achieve this, we must pay attention to two important variables, or things that can be changed, in any experimental study: the independent variable and the dependent variable. An independent variable is manipulated or controlled by the experimenter. In a well-designed experimental study, the independent variable is the only important difference between the experimental and control groups. In our example of how violent television programs affect children’s display of violent behavior, the independent variable is the type of program—violent or nonviolent—viewed by participants in the study (Figure 2.3). A dependent variable is what the researcher measures to see how much effect the independent variable had. In our example, the dependent variable is the number of violent acts displayed by the experimental participants.

Figure 2.8.1. In an experiment, manipulations of the independent variable are expected to result in changes in the dependent variable.

We expect that the dependent variable will change as a function of the independent variable. In other words, the dependent variable depends on the independent variable. A good way to think about the relationship between the independent and dependent variables is with this question: What effect does the independent variable have on the dependent variable? Returning to our example, what effect does watching a half-hour of violent television programming or nonviolent television programming have on the number of incidents of physical aggression displayed on the playground?

Selecting and Assigning Experimental Participants

Now that our study is designed, we need to obtain a sample of individuals to include in our experiment. Our study involves human participants, so we need to determine who to include. Participants are the subjects of psychological research, and as the name implies, individuals who are involved in psychological research actively participate in the process. Often, psychological research projects rely on college students to serve as participants. In fact, the vast majority of research in psychology subfields has historically involved students as research participants (Sears, 1986; Arnett, 2008). But are college students truly representative of the general population? College students tend to be younger, more educated, more liberal, and less diverse than the general population. Although using students as test subjects is an accepted practice, relying on such a limited pool of research participants can be problematic because it is difficult to generalize findings to the larger population.

Our hypothetical experiment involves children, and we must first generate a sample of child participants. Samples are used because populations are usually too large to reasonably involve every member in our particular experiment (Figure 2.4). If possible, we should use a random sample (there are other types of samples, but for the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on random samples). A random sample is a subset of a larger population in which every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. Random samples are preferred because if the sample is large enough we can be reasonably sure that the participating individuals are representative of the larger population. This means that the percentages of characteristics in the sample—sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic level, and any other characteristics that might affect the results—are close to those percentages in the larger population.

In our example, let’s say we decide our population of interest is fourth graders. But all fourth graders is a very large population, so we need to be more specific; instead, we might say our population of interest is all fourth graders in a particular city. We should include students from various income brackets, family situations, races, ethnicities, religions, and geographic areas of town. With this more manageable population, we can work with the local schools in selecting a random sample of around 200 fourth-graders that we want to participate in our experiment.

In summary, because we cannot test all of the fourth graders in a city, we want to find a group of about 200 that reflects the composition of that city. With a representative group, we can generalize our findings to the larger population without fear of our sample being biased in some way.

Figure 2.8.2. Researchers may work with (a) a large population or (b) a sample group that is a subset of the larger population.

Now that we have a sample, the next step of the experimental process is to split the participants into experimental and control groups through random assignment. With random assignment, all participants have an equal chance of being assigned to either group. There is statistical software that will randomly assign each of the fourth graders in the sample to either the experimental or the control group.

Random assignment is critical for sound experimental design. With sufficiently large samples, random assignment makes it unlikely that there are systematic differences between the groups. So, for instance, it would be improbable that we would get one group composed entirely of males, a given ethnic identity, or a given religious ideology. This is important because if the groups were systematically different before the experiment began, we would not know the origin of any differences we find between the groups: Were the differences preexisting, or were they caused by manipulation of the independent variable? Random assignment allows us to assume that any differences observed between experimental and control groups result from the manipulation of the independent variable.

Exercises

Use this online tool to generate randomized numbers instantly and to learn more about random sampling and assignments.

Issues to Consider

While experiments allow scientists to make cause-and-effect claims, they are not without problems. True experiments require the experimenter to manipulate an independent variable, and that can complicate many questions that psychologists might want to address. For instance, imagine that you want to know what effect sex (the independent variable) has on spatial memory (the dependent variable). Although you can certainly look for differences between males and females on a task that taps into spatial memory, you cannot directly control a person’s sex. We categorize this type of research approach as quasi-experimental and recognize that we cannot make cause-and-effect claims in these circumstances.

Experimenters are also limited by ethical constraints. For instance, you would not be able to conduct an experiment designed to determine if experiencing abuse as a child leads to lower levels of self-esteem among adults. To conduct such an experiment, you would need to randomly assign some experimental participants to a group that receives abuse, and that experiment would be unethical.

Interpreting Experimental Findings

Once data is collected from both the experimental and the control groups, a statistical analysis is conducted to find out if there are meaningful differences between the two groups. The statistical analysis determines how likely any difference found is due to chance (and thus not meaningful). In psychology, group differences are considered meaningful, or significant, if the odds that these differences occurred by chance alone are 5 percent or less. Stated another way, if we repeated this experiment 100 times, we would expect to find the same results at least 95 times out of 100.

The greatest strength of experiments is the ability to assert that any significant differences in the findings are caused by the independent variable. This occurs because random selection, random assignment, and a design that limits the effects of both experimenter bias and participant expectancy should create groups that are similar in composition and treatment. Therefore, any difference between the groups is attributable to the independent variable, and now we can finally make a causal statement. If we find that watching a violent television program results in more violent behavior than watching a nonviolent program, we can safely say that watching violent television programs causes an increase in the display of violent behavior.

Candela Citations

- Experimental Research. Authored by: Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by: Hudson Valley Community College. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/adolescent/chapter/experimental-research/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Psychology. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Introduction to Experimental Design. Provided by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://youtu.be/ceWyayKg3QY. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Experimental Research Design. Authored by: Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by: Hudson Valley Community College. Located at: https://hvcc.techsmithrelay.com/0xPJ. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike