As mentioned previously, there are several significant areas of identity development, and each domain may progress through the identity development process independently. Some of the most widely studied domains of identity development include cultural, gender, sexual, ideological, and occupational identity.

Cultural Identity

Cultural identity: Cultural identity refers to how people come to terms with whom they are based on their ethnic, racial, and cultural ancestry. According to the U.S. Census (2012), more than 40% of Americans under the age of 18 are from ethnic minorities. At this point, you are probably aware of the cultural groups to which you belong (i.e., “I am a Latino, middle-class, (almost) college-educated male”). Do you remember the process of coming to awareness of your cultural identity—when did you know you were white and what that meant? Was it during childhood, as a teenager, or reading this chapter? Has your understanding, or acceptance, of your racial heritage changed during your lifetime?

For most people, it does. Just as Piaget organized the growth of children according to various stages of development, cultural scholars have similarly organized racial awareness along models and stages. Before explaining the various models, let us make a couple of general comments about models. One, a model is not the thing it represents. Is the model car you played with as a child the same as the actual automobile? What were the differences? Size, time, maneuverability, details? These same kinds of differences exist between the model of racial identity development and the actual personal process. However, just like the car model gives a relatively accurate picture of the actual automobile, so do the racial identity models. Two, these models are general and not meant to fit perfectly to every individual’s experience. With that said, let us examine the process of coming to an understanding of our racial identity.

Video 1. Demographic Structure of Society–Race and Ethnicity provides more information on the structures of race and ethnicity and how minority and majority identity is constructed.

To better understand this complex process, and in recognition of the above discussion regarding the distinctions in experiences for various cultural groups, we will present four cultural identity models—-Minority, Majority, Bi-racial, and Global Nomads.

Minority Identity Development

Acculturation is a process of social, psychological, and cultural change that stems from the balancing of two cultures while adapting to the prevailing culture of the society. Acculturation is a process in which an individual adopts, acquires, and adjusts to a new cultural environment. Individuals of a differing culture try to incorporate themselves into the more prevalent culture by participating in aspects of the more prevalent culture, such as their traditions, but still hold onto their original cultural values and traditions. The effects of acculturation can be seen at multiple levels in both the devotee of the prevailing culture and those who are assimilating into the culture (Cole, 2018).

At the individual level, the process of acculturation refers to the socialization process by which someone from outside of the dominant culture blends the values, customs, norms, cultural attitudes, and behaviors of the dominant culture. This process has been linked to changes in daily behavior, as well as numerous changes in psychological and physical well-being. As enculturation is used to describe the process of first-culture learning, acculturation can be thought of as second-culture learning.

The fourfold model is a bilinear model that categorizes acculturation strategies along two dimensions. The first dimension concerns the retention or rejection of an individual’s minority or native culture (i.e. “Is it considered to be of value to maintain one’s identity and characteristics?”). Whereas the second dimension concerns the adoption or rejection of the dominant group or host culture. (“Is it considered to be of value to maintain relationships with the larger society?”) From this, four acculturation strategies emerge (Berry, 1997).

Figure 1. Berry’s acculturation model.

- Assimilation occurs when individuals adopt the cultural norms of a dominant or host culture over their original culture. Sometimes this is forced by the dominant culture.

- Separation occurs when individuals reject the dominant or host culture in favor of preserving their culture of origin. Separation is often facilitated by immigration to ethnic enclaves.

- Integration occurs when individuals can adopt the cultural norms of the dominant or host culture while maintaining their culture of origin. Integration leads to, and is often synonymous with, biculturalism.

- Marginalization occurs when individuals reject both their culture of origin and the dominant culture.

Studies suggest that individuals’ respective acculturation strategies can differ between their private and public life spheres (Arends-Tóth & van de Vijver, 2004). For instance, an individual may reject the values and norms of the dominant culture in his private life (separation), while simultaneously adapting to the dominant culture in public parts of his life (i.e., integration or assimilation).

Because people who identify as members of a minority group in the United States tend to stand out or get noticed as “other” or “different,” they also tend to become aware of their identity sooner than individuals who are part of the majority group. For many ethnic minority teens, discovering one’s ethnic identity is an integral part of identity formation. Phinney (1989) proposed a model of ethnic identity development that included stages of unexplored ethnic identity, ethnic identity search, and achieved ethnic identity.

Stage 1: Unexamined Identity. As the name of this stage suggests, the person in stage one of Phinney’s model has little or no concern with ethnicity. They may be too young to pay attention to such matters or just not see the relationship between racial identity and their own life. One may accept the values and beliefs of the majority culture, even if they work against their cultural group.

Stage 2: Conformity. In stage two, the individual moves from a passive acceptance of the dominant culture’s value system to a more active one. They consciously make choices to assimilate or fit in with the dominant culture even if this means putting down or denying their heritage. They may remain at this stage until a precipitating event forces them to question their belief system.

Stage 3: Resistance and Separation. The move from stage two to stage three can be a complicated process as it necessitates a certain level of critical thinking and self-reflection. If you have ever tried to wrestle with aspects of your belief system, then you can imagine the struggle. The move may be triggered by a national event such as the case of “Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, was shot and killed on August 9, by Darren Wilson, a white police officer, in Ferguson, MO (Buchanan). It may be fostered on a more individual scale, such as enrolling in a Women’s Studies class and learning about the specifics of women’s history in America. Martin Luther King Jr. moved to this stage around age six after the mother of King’s White neighborhood friends told them that he could not play with her children anymore because he was Black. A person in this stage may simply reject all of their previously held beliefs and positive feelings about the dominant culture with those of their group, or they may learn how to critically examine and hold beliefs from a variety of cultural perspectives, which leads to stage four.

Stage 4: Integration. The final stage is one where the individual reaches an achieved identity. They learn to value diversity, seeing race, gender, class, and ethnic relations as a complex process instead of an either/or dichotomy. Their aim is to end oppression against all groups, not just their own.

Majority Identity Development

Since White is still considered normative in the United States, White people may take their identity and the corresponding privilege for granted. While we are using the following four stages of development to refer to racial and ethnic identity development, they may also be useful when considering other minority aspects of our identity, such as gender, class, or sexual orientation. Moreover, there is no set age or time period that a person reaches or spends in a particular stage, and not everyone will reach the final stage.

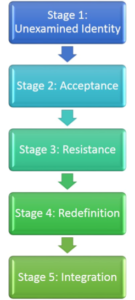

The following model was developed by Rita Hardiman (1994) and contains some similarities with Phinney’s minority identity development model.

Stage 1: Unexamined Identity. This stage is the same for both minority and majority individuals. While children may notice that some of their playmates have different colored skin, they do not fear or feel superior to them.

Stage 2: Acceptance. The move to stage two signals a passive or active acceptance of the dominant ideology—either way, the individual does not recognize that he or she has been socialized into accepting it. When a White person goes the route of passive acceptance, they have no conscious awareness of being White. However, they may hold some subtly racist assumptions such as “[p]eople of color are culturally different, whereas Whites are individuals with no group identity, culture, or shared experience of racial privilege.” Alternatively, White art forms are “classical,” whereas works of art by people of color are considered “ethnic art,” “folk art,” or “crafts” (Martin and Nakayama 132). People in this stage may minimize contact with minorities or act in a “let me help you” fashion toward them. If a White person in this stage follows the active acceptance path, then they are conscious of their White identity and may act in ways that highlight it. Refusing to eat food from other cultures or watch foreign films are examples of the active acceptance path.

Stage 3: Resistance. Just as the move from stage two to stage three in the minority development model required a great deal of critical thought, so does this juncture. Here the members of the majority group cease blaming the members of minority groups for their conditions and see socioeconomic realities as a result of an unjust and biased sociopolitical system. There is an overall move from seeing one’s station in life as a purely individual event or responsibility to a more systemic issue. Here, people may feel guilty about being White and ashamed of some of the historical actions taken by some White people. They may try to associate with only people of color, or they may attempt to exorcise aspects of White privilege from their daily lives.

Stage 4: Redefinition. In this stage, people attempt to redefine what it means to be White without the racist baggage. They can move beyond White guilt and recognize that White people and people of all cultures contain both racist and nonracist elements and that there are many historical and cultural events of which White people can be proud.

Stage 5: Integration. In the last phase, individuals can accept their Whiteness or other majority aspects of their identity and integrate it into other parts of their lives. There are simultaneous self-acceptance and acceptance of others.

Figure 2. Hardiman’s stages of majority identity development

Bi- or Multiracial Identity Development

Originally, people thought that bi-racial individuals followed the development model of minority individuals. However, given that we now know that race is a social construct, it makes sense to realize that a person of mixed racial ancestry is likely to be viewed differently (from both the dominant culture and the individual’s own culture) than a minority individual. Thus, they are likely to experience a social reality unique to their experience. The following five-stage model is derived from the work of W.S. Carlos Poston.

Stage 1: Personal Identity. Poston’s first stage is much like the unexamined identity stage in the previous two models. Again, children are not aware of race as a value-based social category and derive their personal identity from individual personality features instead of cultural ones.

Stage 2: Group Categorization. In the move from stage one to two, the person goes from no racial or cultural awareness to having to choose between one or the other. In a family where the father is Black, and the mother is Japanese, the child may be asked by members of both families to decide if he or she is Black or Japanese. Choosing both is not an option at this stage.

Stage 3: Enmeshment/Denial. Following the choice made in stage two, individuals attempt to immerse themselves in one culture while denying ties to the other. This process may result in guilt or feelings of distance from the parent and family whose culture was rejected in stage two. If these feelings are resolved, then the child moves to the next stage. If not, they remain here.

Stage 4: Appreciation. When feelings of guilt and anger are resolved, the person can work to appreciate all of the cultures that shape their identity. While there is an attempt to learn about the diversity of their heritage, they will still identify primarily with the culture chosen in stage two.

Stage 5: Integration. In the fifth and final stage, the once fragmented parts of the person’s identity are brought together to create a unique whole. There is an integration of cultures throughout all facets of a person’s life—dress, food, holidays, spirituality, language, and communication.

Global Nomads

People who move around a lot may develop a multicultural identity as a result of their extensive international travel. International teachers, business people, and military personnel are examples of global nomads (Martin & Nakayama). One of the earlier theories to describe this model of development was called the U-curve theory because the stages were thought to follow the pattern of the letter U. The model has since been revised in the form of a W or a series of ups and downs. This pattern is thought better to represent the up and down nature of this process.

Figure 3. Identity development model for global nomads.

Stage 1: Anticipation and Excitement. If you have ever planned for an international trip, what were some of the things you did to prepare? Did you do something like buy a guidebook to learn some of the native customs, figure out the local diet to see if you would need to make any special accommodations, learn the language, or at least some handy phrases perhaps? All of these acts characterize stage one in which people are filled with positive feelings about their upcoming journey and try to ready themselves.

Stage 2: Culture Shock. Once the excitement has worn off or you are confronted with an unexpected or unpleasant event, you may experience culture shock. This experience is the move from the top of the U or W to the bottom. Culture shock can result from physical, psychological, or emotional causes often correlating with an unpleasant and unfamiliar event. When individuals have spent most of their lives in a particular country, they will most likely experience culture shock when they travel overseas. The differences in cultural language, customs, and even food may be overwhelming to someone that has never experienced them before.

Stage 3: Adaptation. The final stage at the top of the U and W is a feeling of comfortableness: being somewhat familiar with the new cultural patterns and beliefs. After spending more time in a new country and learning its cultural patterns and beliefs, individuals may feel more welcomed into the society by accepting and adapting to these cultural differences.

Gender Identity, Gender Constancy, and Gender Roles

Gender identity is one’s self-conception of their gender. Sex is the term to refer to the biological differences between males and females, such as genitalia and genetic differences. While gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, such as norms, roles, and relationships between groups of women and men. Cisgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex, while transgender is a term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond with their birth sex.

Gender expression, or how one demonstrates gender (based on traditional gender role norms related to clothing, behavior, and interactions), can be feminine, masculine, androgynous, or somewhere along a spectrum. Many adolescents use their analytic, hypothetical thinking to question traditional gender roles and expression. If their genetically assigned sex does not line up with their gender identity, they may refer to themselves as transgender, non-binary, or gender-nonconforming.

Preschool-aged children become increasingly interested in finding out the differences between boys and girls both physically and in terms of what activities are acceptable for each. While two-year-olds can identify some differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. This self-identification, or gender identity, is followed sometime later with gender constancy, or the understanding that superficial changes do not mean that gender has actually changed. For example, if you are playing with a two-year-old boy and put barrettes in his hair, he may protest saying that he doesn’t want to be a girl. By the time a child is four years old, they have a solid understanding that putting barrettes in their hair does not change their gender.

Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes.

Children may also use gender stereotyping readily. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing the attitudes, traits, or behavior patterns of women or men. A recent research study examined four- and five-year-old children’s predictions concerning the sex of the persons carrying out a variety of common activities and occupations on television. The children’s responses revealed strong gender-stereotyped expectations. They also found that children’s estimates of their own future competence indicated stereotypical beliefs, with the females more likely to reject masculine activities.

Children who are allowed to explore different toys, who are exposed to non-traditional gender roles, and whose parents and caregivers are open to allowing the child to take part in non-traditional play (allowing a boy to nurture a doll, or allowing a girl to play doctor) tend to have broader definitions of what is gender appropriate, and may do less gender stereotyping.

Fluidity and uncertainty regarding sex and gender are especially common during early adolescence when hormones increase and fluctuate, creating a difficulty of self-acceptance and identity achievement (Reisner et al., 2016). Gender identity is becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving, and some adolescents may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty by adopting more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013). Those that identify as transgender or ‘other’ face even more significant challenges.

Watch It

Video 2. This clip from Upworthy shows how some children were surprised to meet women in traditionally male occupations.

Stages of Gender Identity Development

The National Center on Parent, Family, and Community Engagement identified several stages of gender identity development, as outlined below.

Infancy. Children observe messages about gender from adults’ appearances, activities, and behaviors. Most parents’ interactions with their infants are shaped by the child’s gender, and this in turn also shapes the child’s understanding of gender (Fagot & Leinbach, 1989; Witt, 1997; Zosuls, Miller, Ruble, Martin, & Fabes, 2011).

18–24 months. Toddlers begin to define gender, using messages from many sources. As they develop a sense of self, toddlers look for patterns in their homes and early care settings. Gender is one way to understand group belonging, which is important for secure development (Kuhn, Nash & Brucken, 1978; Langlois & Downs, 1980; Fagot & Leinbach, 1989; Baldwin & Moses, 1996; Witt, 1997; Antill, Cunningham, & Cotton, 2003; Zoslus, et al., 2009).

Ages 3–4. Gender identity takes on more meaning as children begin to focus on all kinds of differences. Children begin to connect the concept “girl” or “boy” to specific attributes. They form stronger rules or expectations for how each gender behaves and looks (Kuhn, Nash, & Brucken 1978; Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2004; Halim & Ruble, 2010).

Ages 5-6. At these ages, children’s thinking may be rigid in many ways. For example, 5- and 6-year-olds are very aware of rules and of the pressure to comply with them. They do so rigidly because they are not yet developmentally ready to think more deeply about the beliefs and values that many rules are based on. For example, as early educators and parents know, the use of “white lies” is still hard for them to understand. Researchers call these ages the most “rigid” period of gender identity (Weinraub et al., 1984; Egan, Perry, & Dannemiller, 2001; Miller, Lurye, Zosuls, & Ruble, 2009). A child who wants to do or wear things that are not typical of his gender is probably aware that other children find it strange. The persistence of these choices, despite the negative reactions of others, shows that these are strong feelings. Gender rigidity typically declines as children age (Trautner et al., 2005; Halim, Ruble, Tamis-LeMonda, & Shrout, 2013). With this change, children develop stronger moral impulses about what is “fair” for themselves and other children (Killen & Stangor, 2001).

It is important to understand these typical and normal attempts for children to understand the world around them. It is helpful to encourage children and support them as individuals, instead of emphasizing or playing into gender roles and expectations. You can foster self-esteem in children of any gender by giving all children positive feedback about their unique skills and qualities. For example, you might say to a child, “I noticed how kind you were to your friend when she fell down” or “You were very helpful with clean-up today—you are such a great helper” or “You were such a strong runner on the playground today.”

Encouraging Healthy Gender Development

You can see more of their resources and tips for healthy gender development by reading Healthy Gender Development and Young Children.

Theories of Gender Identity Development

Biological Approach

The biological approach explores how gender identity development is influenced by genetics, biological sex characteristics, brain development, and hormone exposure.

Humans usually have 23 pairs of chromosomes, each containing thousands of genes that govern various aspects of our development. The 23rd pair of chromosomes are called the sex chromosomes. This pair determines a person’s sex, among other functions. Most often, if a person has an XX pair, they will develop into a female, and if they have an XY pair, they will be male.

Around the sixth week of prenatal development, the SRY gene on the Y chromosome signals the body to develop as a male. This chemical signal triggers a cascade of other hormones that will tell the gonads to develop into testes. If the embryo does not have a Y or the if, for some reason, the SRY gene is missing or not activate, then the embryo will develop female characteristics. The baby is born and lives as a female, but genetically her chromosomes are XY. Rat studies have found that the reverse is also possible. Researchers implanted the SRY gene in rats with XX chromosomes, and the result was male baby mice.

Individuals with atypical chromosomes may also develop differently than their typical XX or XY counterparts. These chromosomal abnormalities include syndromes where a person may have only one sex chromosome or three sex chromosomes. Turner’s Syndrome is a condition where a female has only one X chromosome (XO). This missing chromosome results in a female external appearance but lacking ovaries. These XO females do not mature through puberty like XX females and they may also have webbed skin around the neck. Cognitively, these females tend to have high verbal skills, poor spatial and math skills, and poor social adjustment.

Klinefelter’s Syndrome is a condition where a male has an extra X chromosome (XXY). This XXY combination results in male genitals, although their genitals may be underdeveloped even into adulthood. Even after puberty, they tend to have less body and facial hair and may develop breasts. From infancy, these children often have a passive, cooperative, and shy personality that remains into adulthood. Cognitively, they are often late to talk and have poor language and reading skills.

As we learned in the physical development chapter, sex hormones cause biological changes to the body and brain. While the same-sex hormones are present in males and females, the amount of each hormone and the effect of that hormone on the body is different. Males have much higher levels of testosterone than females. In the womb, testosterone causes the development of male sex organs. It also impacts the hypothalamus, causing an enlarged sexually dimorphic nucleus, and results in the ‘masculinization’ of the brain. Around the same time, testosterone may contribute to greater lateralization of the brain, resulting in the two halves working more independently of each other. Testosterone also affects what we often consider male behaviors, such as aggression, competitiveness, visual-spatial skills, and higher sex drive.

Cognitive Approaches

Cognitive learning theory states that children develop gender at their own levels. At each stage, the child thinks about gender characteristically. As a child moves forward through stages, their understanding of gender becomes more complex.

The following cognitive model, formulated by Kohlberg, asserts that children recognize their gender identity around age three but do not see it as relatively fixed until five to seven. This identity marker provides children with a schema, a set of observed or spoken rules for how social or cultural interactions should happen. Information about gender is gathered from the environment; thus, children look for role models to emulate maleness or femaleness as they grow.

Stage 1: Gender Labeling (2-3.5 years). The child can label their gender correctly.

Stage 2: Gender Stability (3.5-4.5 years). The child’s gender remains the same across time.

Stage 3: Gender Constancy (6 years). The child’s gender is independent of external features (e.g., clothing, hairstyle).

Once children form a basic gender identity, they start to develop gender schemas. These gender schemas are organized set of gender-related beliefs that influence behaviors. The formation of these schemas explains how gender stereotypes become so psychologically ingrained in our society.

According to Sandra Bem’s Gender Schema Theory, gender schemas can be organized into four general categories. The sex-type schema is the belief that gender matches biological sex. Sex-reversed schema is when gender is the opposite of biological sex. Possessing both masculine and feminine traits is an androgynous schema. While possessing few masculine or feminine traits is an undifferentiated schema.

Social Learning Approach

Social Learning Theory suggests that gender role socialization is a result of how parents, teachers, friends, schools, religious institutions, media, and others send messages about what is acceptable or desirable behavior for males or females. if children receive positive reinforcement, they are motivated to continue a particular behavior. If they receive punishment or other indicators of disapproval, they are motivated to stop that behavior. In terms of gender development, children receive praise if they engage in culturally appropriate gender displays and punishment if they do not. When aggressiveness in boys is met with acceptance or a “boys will be boys” attitude, but a girl’s aggressiveness earns them little attention, the two children learn different meanings for aggressiveness related to their gender development. Thus, boys may continue being aggressive while girls may drop it out of their repertoire.

This socialization begins early—in fact, it may even begin when a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and potential on the part of a parent. And this stereotyping continues to guide perception through life. Consider parents of newborns. Shown a 7-pound, 20-inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delicate, and frustrated when crying (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Female infants are held more, talked to more frequently, and given direct eye contact, while male infants’ play is often mediated through a toy or activity.

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, and superhero paraphernalia, active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Daughters are often given dolls and dress-up apparel that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender normative behavior (Caldera, Huston, and O’Brien 1998).

Sons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion, while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home, such as cleaning or cooking, that are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems, and daughters are more likely to be given assistance even when they are working on an answer. This impatience is reflected in teachers waiting less time when asking a female student for an answer than when asking for a reply from a male student (Sadker and Sadker, 1994). Girls are given the message from teachers that they must try harder and endure in order to succeed while boys’ successes are attributed to their intelligence. Of course, the stereotypes of advisors can also influence which kinds of courses or vocational choices girls and boys are encouraged to make.

Friends discuss what is acceptable for boys and girls, and popularity may be based on modeling what is considered ideal behavior or appearance for the sexes. Girls tend to tell one another secrets to validate others as best friends, while boys compete for position by emphasizing their knowledge, strength or accomplishments. This focus on accomplishments can even give rise to exaggerating accomplishments in boys, but girls are discouraged from showing off and may learn to minimize their accomplishments as a result.

Gender messages abound in our environment. But does this mean that each of us receives and interprets these messages in the same way? Probably not. In addition to being recipients of these cultural expectations, we are individuals who also modify these roles (Kimmel, 2008).

One interesting recent finding is that girls may have an easier time breaking gender norms than boys. Girls who play with masculine toys often do not face the same ridicule from adults or peers that boys face when they want to play with feminine toys. Girls also face less ridicule when playing a masculine role (like doctor) as opposed to a boy who wants to take a feminine role (like caregiver).

The Impact of Gender Discrimination

How much does gender matter? In the United States, gender differences are found in school experiences. Even in college and professional school, girls are less vocal in class and much more at risk for sexual harassment from teachers, coaches, classmates, and professors. These gender differences are also found in social interactions and in media messages. The stereotypes that boys should be strong, forceful, active, dominant, and rational, and that girls should be pretty, subordinate, unintelligent, emotional, and talkative are portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music. In adulthood, these differences are reflected in income gaps between men and women (women working full-time earn about 74 percent of the income of men), in higher rates of women suffering rape and domestic violence, higher rates of eating disorders for females, and in higher rates of violent death for men in young adulthood.

Gender differences in India can be a matter of life and death as preferences for male children have been historically strong and are still held, especially in rural areas (WHO, 2010). Male children are given preference for receiving food, breast milk, medical care, and other resources. In some countries, it is no longer legal to give parents information on the sex of their developing child for fear that they will abort a female fetus. Clearly, gender socialization and discrimination still impact development in a variety of ways across the globe. Gender discrimination generally persists throughout the lifespan in the form of obstacles to education, or lack of access to political, financial, and social power.

Transgender Identity Development

Individuals who identify with a role that is different from their biological sex are called transgender. Approximately 1.4 million U.S. adults or .6% of the population are transgender, according to a 2016 report (Flores et al., 2016).

Transgender individuals may choose to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy so that their physical being is better aligned with gender identity. They may also be known as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM). Not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies; many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as another gender. This expression is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to another gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to a different gender is not the same as identifying as transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and it is not necessarily an expression against one’s assigned gender (APA 2008).

After years of controversy over the treatment of sex and gender in the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (Drescher 2010), the most recent edition, DSM-5, responded to allegations that the term “gender identity disorder” is stigmatizing by replacing it with “gender dysphoria.” Gender identity disorder as a diagnostic category stigmatized the patient by implying there was something “disordered” about them. Removing the word “disorder” also removed some of the stigmas while still maintaining a diagnosis category that will protect patient access to care, including hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery.

In the DSM-5, gender dysphoria is a condition of people whose gender at birth is contrary to the one with which they identify. For a person to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, there must be a marked difference between the individual’s expressed/experienced gender and the gender others would assign him or her, and it must continue for at least six months. In children, the desire to be of the other gender must be present and verbalized (APA, 2013). Changing the clinical description may contribute to greater acceptance of transgender people in society. A 2017 poll showed that 54% of Americans believe gender is determined by sex at birth, and 32% say society has “gone too far” in accepting transgender people; views are sharply divided along political and religious lines (Salam, 2018).

Many psychologists and the transgender community are now advocating an affirmative approach to transgender identity development. This approach advocates that gender non-conformity is not a pathology but a normal human variation. Gender non-conforming children do not systemically need mental health treatment if they are not “pathological.” However, caregivers of gender non-conforming children can benefit from a mixture of psycho-educational and community-oriented interventions. Some children or teens may benefit from counseling or other interventions to help them cope with familial or societal reactions to their gender nonconformity.

Studies show that people who identify as transgender are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as non-transgender individuals; they are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2010; Giovanniello, 2013). Trans women of color are most likely to be victims of abuse. There are also systematic aggressions, such as “deadnaming,” (whereby trans people are referred to by their birth name and gender), laws restricting transpersons from accessing gender-specific facilities (e.g., bathrooms), or denying protected-class designations to prevent discrimination in housing, schools, and workplaces. Organizations such as the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs and Global Action for Trans Equality work to prevent, respond to, and end all types of violence against transgender and homosexual individuals. These organizations hope that by educating the public about gender identity and empowering transgender individuals, this violence will end.

Like other domains of identity, stage models for transgender identity development have helped describe a typical progression in identity formation. Lev’s Transgender Emergence Model looks at how trans people come to understand their identity. Lev is working from a counseling/therapeutic point of view, thus this model talks about what the individual is going through and the responsibility of the counselor.

Stage 1: Awareness. In this first stage of awareness, gender-variant people are often in great distress; the therapeutic task is the normalization of the experiences involved in emerging as transgender.

Stage 2: Seeking Information/Reaching Out. In the second stage, gender-variant people seek to gain education and support about transgenderism; the therapeutic task is to facilitate linkages and encourage outreach.

Stage 3: Disclosure to Significant Others. The third stage involves the disclosure of transgenderism to significant others (spouses, partners, family members, and friends); the therapeutic task involves supporting the transgender person’s integration in the family system.

Stage 4: Exploration (Identity & Self-Labeling). The fourth stage involves the exploration of various (transgender) identities; the therapeutic task is to support the articulation and comfort with one’s gendered identity.

Stage 5: Exploration (Transition Issues & Possible Body Modification). The fifth stage involves exploring options for transition regarding identity, presentation, and body modification; the therapeutic task is the resolution of the decision and advocacy toward their manifestation.

Stage 6: Integration (Acceptance & Post-Transition Issues). In the sixth stage, the gender-variant person can integrate and synthesize (transgender) identity; the therapeutic task is to support adaptation to transition-related issues.

Sexual Identity

Sexual identity is how one thinks of oneself in terms of to whom one is romantically or sexually attracted (Reiter, 1989). Sexual identity may also refer to sexual orientation identity, which is when people identify or dis-identify with a sexual orientation or choose not to identify with a sexual orientation (APA, 2009). Sexual identity and sexual behavior are closely related to sexual orientation but they are distinguished (Reiter, 1989), with identity referring to an individual’s conception of themselves, behavior referring to actual sexual acts performed by the individual, and sexual orientation referring to romantic or sexual attractions toward persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, to both sexes or more than one gender, or no one.

Sexual orientation is typically discussed as four categories: heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the other sex; homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the same sex; bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; and asexuality, no attraction to either sex. However, others view sexual orientation as less categorical and more of a continuum.

Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. He created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual (Figure 4). In his 1948 work, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey writes, “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats … The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects” (Kinsey, 1948).

Figure 4. The Kinsey scale indicates that sexuality can be measured by more than just heterosexuality and homosexuality.

Later scholarship by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick expanded on Kinsey’s notions. She coined the term “homosocial” to oppose “homosexual,” describing nonsexual same-sex relations. Sedgwick recognized that in U.S. culture, males are subject to a clear divide between the two sides of this continuum, whereas females enjoy more fluidity. This difference can be illustrated by the way women in the United States can express homosocial feelings (nonsexual regard for people of the same sex) through hugging, handholding, and physical closeness. In contrast, U.S. males refrain from these expressions since they violate the heteronormative expectation that male sexual attraction should be exclusively for females. Research suggests that it is easier for women to violate these norms than men because men are subject to more social disapproval for being physically close to other men (Sedgwick, 1985).

The issue of sexual identity and orientation can be further complicated when considering differences in romantic attraction versus sexual attraction. A person could be romantically interested in the same sex, different sex, or any gender but could feel sexually attracted to the same or different group. For example, an individual could be interested in a romantic relationship with males but be sexually attracted to males and females. Alternatively, someone may be open to a romantic relationship with any gender but is primarily only sexually attracted to one sex.

The United States is a heteronormative society, meaning it assumes that heterosexuality is the norm and that sexual orientation is biologically determined and unambiguous. Consider that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know that you were straight?” (Ryle 2011). However, there is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. Research has been conducted to study the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no definitive evidence that links sexual orientation to one factor (APA, 2008).

According to current understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (APA, 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Homosexual women (also referred to as lesbians), homosexual men (also referred to as gays), and bisexuals of both genders may have very different experiences of discovering and accepting their sexual orientation. At the point of puberty, some may be able to announce their sexual orientations, while others may be unready or unwilling to make their homosexuality or bisexuality known since it goes against U.S. society’s historical norms (APA 2008).

Most of the research on sexual orientation identity development focuses on the development of people who are attracted to the same sex. Many people who feel attracted to members of their own sex ‘come out’ at some point in their lives. Coming out is described in three phases. The first phase is the phase of “knowing oneself,” and the realization emerges that one is sexually and emotionally attracted to members of one’s own sex. This step is often described as an internal coming out and can occur in childhood or at puberty, but sometimes as late as age 40 or older. The second phase involves a decision to come out to others, e.g., family, friends, and/or colleagues. The third phase involves living openly as an LGBT person (Human Rights Campaign, 2007). In the United States today, people often come out during high school or college age. At this age, they may not trust or ask for help from others, especially when their orientation is not accepted in society. Sometimes they do not inform their own families.

According to Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, Braun (2006), “the development of a lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB), sexual identity is a complex and often difficult process. Unlike members of other minority groups (e.g., ethnic and racial minorities), most LGB individuals are not raised in a community of similar others from whom they learn about their identity. Their identity may not be reinforced and supported by their community. Instead, “LGB individuals are often raised in communities that are either ignorant of or openly hostile toward homosexuality.”

Cass’ Homosexual Identity Model

Cass (1979) was one of the early creators of a model for explaining how individuals progress through the development of a homosexual identity. Cass proposed six stages. It may take several years to get through a particular stage and not all make it to stage 6. “Foreclosure” (when an individual denies their identity or hides it from others) can occur at any stage and halt the process.

Stage 1: Identity Awareness. The individual is aware of being “different” from others.

Stage 2: Identity Comparison. The individual compares their feelings and emotions to those they identify as heterosexual.

Stage 3: Identity Tolerance. The individual tolerates their identity as being non-heterosexual.

Stage 4: Identity Acceptance. The individual accepts their new identity and begins to become active in the “gay community.”

Stage 5: Identity Pride. The individual becomes proud of their identity and becomes fully immersed in “gay culture.”

Stage 6: Identity Synthesis. The individual fully accepts their identity and synthesizes their former “heterosexual life” and their new identity.

A criticism of Cass’ model is that her research primarily studied white gay men and lesbian women of middle- to upper-class status. This stage model is not necessarily reflective of the process a bisexual or transgender individual may experience and, ultimately, may not be reflective of the process experienced by all non-heterosexual individuals.

Some individuals with unwanted sexual attractions may choose to actively dis-identify with a sexual minority identity, which creates a different sexual orientation identity from their actual sexual orientation. Sexual orientation identity, but not sexual orientation, can change through psychotherapy, support groups, and life events. A person who has homosexual feelings can self-identify in various ways. An individual may come to accept an LGB identity, to develop a heterosexual identity, to reject an LGB identity while choosing to identify as ex-gay, or to refrain from specifying a sexual identity (APA, 2009).

Figure 5. This identity spectrum shows the fluidity between sex, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation.

Video 3. Demographic Structure of Society–Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation explains various aspects of gender and sexual identity.

Ideological Group Identity

Religious identity is a specific type of identity formation. Particularly, it is the sense of group membership to a religion and the importance of this group membership as it pertains to one’s self-concept. Religious identity is not necessarily the same as religiousness or religiosity. Although these terms share a commonality, religiousness and religiosity refer to both the value of religious group membership as well as participation in religious events (e.g., going to church) (Arweck & Nesbitt, 2010; King et al., 1997). Religious identity, on the other hand, refers specifically to religious group membership regardless of religious activity or participation.

Similar to other forms of identity formation, such as ethnic and cultural identity, the religious context can generally provide a perspective from which to view the world, opportunities to socialize with a spectrum of individuals from different generations, and a set of fundamental principles to live out (King & Boratzis, 2004). These foundations can come to shape an individual’s identity.

The religious views of teens are often similar to those of their families (Kim-Spoon, Longo, & McCullough, 2012). Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few reject the religion of their families entirely.

An adolescent’s political identity is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party, and their teenage children reflect their parents’ lack of party affiliation. Although adolescents do tend to be more liberal than their elders, especially on social issues (Taylor, 2014), like other aspects of identity formation, adolescents’ interest in politics is predicted by their parents’ involvement and by current events (Stattin et al., 2017).

Occupational Identity Development

While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job and often worked as an apprentice or part-time in such occupations as teenagers, this is rarely the case today. Occupational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. Besides, many of the jobs held by teens are not in occupations that most teens will seek as adults. (See career development theories for more information).