II. State Judicial System

The material to this point has discussed the highest court in the federal system, the U.S. Supreme Court, and its power to interpret the U.S. Constitution. Throughout this text, we will examine cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court that impact our lives, and specifically, those that are relevant to law enforcement. However, there is another judicial process operating which affects us as much, if not more than, the federal judicial process: the New York State judicial system.

The NY judicial system is divided geographically into four judicial departments and 13 judicial districts. Cases are heard first in the lower level or trial courts, and then move through the process by appeals of lower court decisions. In New York the lower level or trial courts for felony criminal cases are the superior courts — the County or Supreme Court, although criminal cases generally start with arraignment in the local criminal court. The system for civil cases is similar, with matters divided into the type of case or the dollar amounts involved. Four our purposes in this text, criminal felony cases in New York progress as follows:

1. Trial Level Court – Supreme or County Court

After arraignment in a local criminal court and indictment by a grand jury, the felony criminal case begins in the trial court. This court will hear testimony, consider evidence and render a verdict, whether through a jury or judge (bench trial).

2. Intermediate Appellate Court – Appellate Division of the Supreme Court

There are four Appellate Divisions of the Supreme Court, one in each judicial department. The Appellate Divisions hear civil and criminal appeals from the trial courts as well as civil appeals from the Appellate Terms and County Courts. Although the People, or prosecution, in a criminal case cannot appeal an acquittal (that would violate the protection against Double Jeopardy), they may seek appellate review on certain lower court rulings within a case.

3. Final Appellate Court – New York State Court of Appeals

The highest court in the New York State judicial system is the New York Court of Appeals. And, like the U.S. Supreme Court, the New York Court of Appeals does not hear every case that it is requested to hear; appellants must apply for permission (“leave to appeal”), and only a small fraction of the requested cases are granted this permission.

Just as the U.S. Supreme Court is the final interpreter of the U.S. Constitution, the NY Court of Appeals is the final authority over the NY Constitution.

THE NEW YORK CONSTITUTION

The New York Constitution is a more comprehensive document than the federal Constitution; it incorporates many of the same rights and includes others. For example, the NY Constitution has as its first Article its Bill of Rights, rather than the Bill of Rights as separate amendments as the federal Constitution does. The entire NY Constitution is set out on the New York official website.

https://www.dos.ny.gov/info/constitution.html

Since the NY Court of Appeals is the final authority over interpreting the NY Constitution, a case that involves strictly NY law will be heard exclusively in the NY state judicial system. If there is an issue in a state law case that involves federal constitutional issues, the case may be allowed to proceed in the federal system, but only after all state remedies have been exhausted and only by permission.

THE HISTORY OF THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION:

As already mentioned above, New York’s first Constitution was adopted in 1777. However, since that time, the NYS’ Constitution has been rewritten 3 more times, in 1821, 1846 and 1894. NYS’s current Constitution is from 1938. It was not rewritten but modified by amendments to the 1894 Constitution.

THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION OF 1777:

New York’s first Constitution was drafted right after New York’s Fourth Provincial Congress declared New York independent of Great Britain in 1776. It was formally adopted by the Convention of Representatives of the State of New York, meeting in the upstate town of Kingston, on April 20th, 1777.

The Constitution declared the possibility of reconciliation between British and its former American colonies even if uncertain and remote. The Constitution then declared that there was now the need for the creation of a new New York government for the preservation of internal peace, virtue, and good order.

This new Constitution created three governmental branches: An executive branch, a judicial branch and a legislative branch. The Constitution called for the election of a governor, 24 senators and 70 assemblymen from 14 declared counties who were to be elected by eligible male inhabitants. The right to vote was tied to the ownership of a certain amount of property. The Constitution also guaranteed the right to a jury trial.

THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION OF 1821:

At the 1821 Convention there was a bitter debate over the property qualifications for voting. Many at the convention felt the need to retain property ownership was a qualification for the right to vote was necessary to avoid as Chancellor James Kent, the state’s leading legal scholar and the head of its highest Court said “corruption, injustice, violence and tyranny”.

However, Governor Daniel Tompkins, the chairman of the Convention who had led the State militias during the War of 1812 argued that all the men who fought in the war should have a right to vote. A motion to retain property qualifications for voting was defeated by a vote of 19 to 100 and with it one of the most important political developments in New York’s history was established.

The New York State Constitution of 1821 had many flaws. It did not give women the right to vote. It effectively disenfranchised free African American men by requiring them to own at least $250 of property to vote. Nevertheless, it set the stage for major social and political change. As the state’s economy moved from agricultural to industrial, and with influx of immigrants arriving from around the world, the right of to vote without the need to own land helped establish eventual broad-based suffrage.

THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION OF 1846:

Several changes were established in the 1846 rewrite of the NYS Constitution. Most notably where the abolishment of the Court of Chancery, the Court for the Correction of Errors and the New York State Circuit Courts. Jurisdiction was moved to the New York Supreme Court and appellate jurisdiction to the New York Court of Appeals. The Attorney General, Secretary of State, Comptroller, Treasurer and State Engineer offices went from appointed cabinet offices to elected officials.

THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION OF 1894:

The rewrite of the 1894 Constitution included the reduction in the number of years in office for the governor and lieutenant governor from three to two. The number of state senators and assemblymen was increased. The year of cabinet officer elections was changed. The State Park Reserve was given perpetual protection. Convict labor was abolished. Voting machines were allowed to be used.

THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1938:

While the Constitution was not rewritten at this convention, 57 amendments to the 1894 Constitution were presented to the voters. Some of the notable changes approved by vote were the setting out the rights of public works workers, the removal of a debt ceiling for NYC so the city could finance a public rapid transport system, and permission for the State legislature to provide funds for transportation to parochial schools.

MUST THE NY COURT OF APPEALS ALWAYS FOLLOW THE U.S. SUPREME COURT?

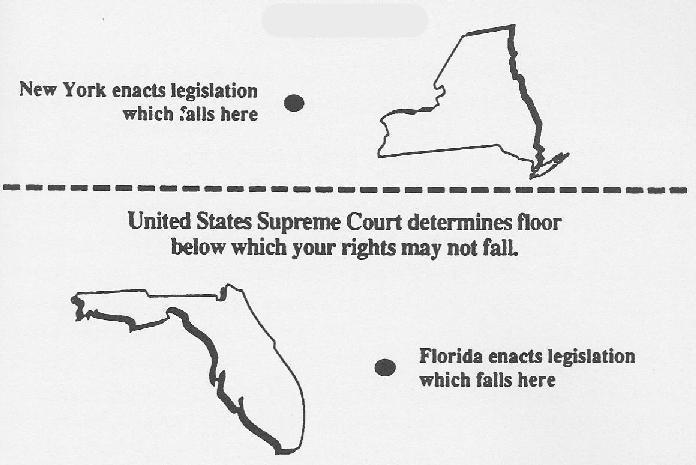

Not necessarily. Although the U.S. Supreme Court is known as the “highest court in the land”, a state is free to carve out greater rights for its citizens than the federal government allows. This authority was recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in Oregon v. Hass 420 U.S. 714 (1975), a summary of which follows this chapter. So, the U.S. Supreme Court sets minimal individual rights that are guaranteed to every American citizen, but states can enhance those rights, which New York often does. In the next several chapters, we will explore areas in which the NY rules set by cases decided by the NY Court of Appeals are different from the rules established by the U.S. Supreme Court. The NY Court of Appeals is able to do that as long as it decides the case under the New York Constitution, not the U.S. Constitution. It is important to remember, however, that the states cannot enact legislation or decide cases that would give individuals less rights than they enjoy at the federal level.

Example : Although there is a right to counsel guaranteed both at the federal and state levels, the NY Court of Appeals has held that once a person in custody on a criminal charge invokes his right to counsel, he cannot then change his mind and waive his right to counsel unless a lawyer is present at the waiver. That differs from federal practice, which allows a person charged and who has initially requested counsel to change his mind and waive that right as long as the waiver is voluntarily made. See the discussion of People v. Cunningham, 49 NY2d 203 (1980) in the Chapter on Right to Counsel in New York.

This can be confusing, especially considering that the two judicial bodies may be looking at very similar, or even identical language, and coming up with different reasoning. For example, here is the language from the Fourth amendment to the U.S. Constitution on search and seizure:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

And here is Section 12 of Article I of the New York Constitution:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Identical wording. And yet, the US Supreme Court and the NY Court of Appeals often come to different conclusions on cases revolving around search and seizure. For example, in the People v. Diaz, 81 N.Y. 2d 106(1993), which is summarized at the end of this chapter, the NY Court of Appeals used Article I, Section 12 of the NY Constitution to prohibit police from using a warrantless search of a suspect’s pocket based on a “plain touch” exception when they felt drugs (but not a weapon) during a legal pat-down. The NY Court of Appeals restricted police use of stop-and-frisk to weapons only, and declined to allow a “plain touch” exception in which an officer could tell during the frisk that an object was contraband (drugs). In the U.S. Supreme Court that same year, the “plain touch” exception to the requirement that a warrant be obtained was officially recognized in Minnesota v. Dickerson, 113 S. Ct. 2130 (1993). Two different results in interpreting identical language. Notice the NY decision works to give NY citizens greater rights than the federal decision. See the diagram immediately following this section for a visual example.

For another case example of the NY Court of Appeals deviating from the US Supreme Court, see People v. P.J. Video, 68 NY 2d 296 (1986), summary attached.

TERMS TO NOTE

Stare Decisis and Case Precedent: Stare Decisis is the idea that decisions on issues should be the same from day to day. Case Precedent is closely related, and occurs when another case with similar issues of law and facts is used as an example for the current case. Judges will generally “follow precedent” unless one of the parties can show that the other case was decided incorrectly or was different in some important way.

Landmark Case: When courts do not follow case precedent and rule against the prevailing case authority. This could happen if the Court and/or society in general feels that things have changed since the last decision on a topic. It can also refer to any highly significant decision.

Due process: The duty of government to follow rules in legal proceedings. The U.S. Constitution guarantees due process in the 5th and 14th Amendments. This means that a person may not have life, liberty or property taken away without his or her day in court.

Opinion: 1. The written explanation by the court about the decision in a case. 2. In an appeal when there is more than one Judge the “winning” decision is called the “majority opinion.” Only the majority opinion can be used as binding precedent in future cases.

Concur: A “concurring” opinion agrees with the decision of the majority either for the same or for different reasons.

Dissent: A “dissenting” opinion disagrees with the majority opinion because of the reasoning and/or the principles of law the majority used to decide the case.

Habeas corpus: Meaning literally in Latin: “You have the body.” The name of an order used to bring a person to a court or Judge to decide if that person is being denied his or her freedom unlawfully. This is generally used by a prisoner seeking his release by claiming he is being held illegally.

Federalism: A principle of government that defines the relationship between the central government at the national level and governments at the regional, state, or local levels. Under this principle of government, power and authority is allocated between the national and local governmental units, such that each unit is delegated a sphere of power and authority only it can exercise, while other powers must be shared.

HOW TO CITE A CASE

A case citation is like its address; it enables readers to locate the case decision in law books. So, for the Marbury v. Madison case citation:

Marbury v. Madison , 5 U.S. 137 (1803)

Marbury is the name of the plaintiff in the case (this occasionally changes through appeals)

Madison is the defendant

5 is the number of the volume of the law book in which the case is printed, or “reported”

U.S. is the abbreviation for the name of the set of law books the case appears in; for this case it is Unites States Supreme Court reports. If the case was a NY Court of Appeals case, the abbreviation would be N.Y. or N.Y.2nd or N.Y. 3rd

137 is the page number in the volume where the case begins

(1803) is the year the case was decided

When briefing cases, it is good practice to start the brief with the official case citation. Briefing a case is the topic of the next chapter, so read on………