Audition (Hearing)

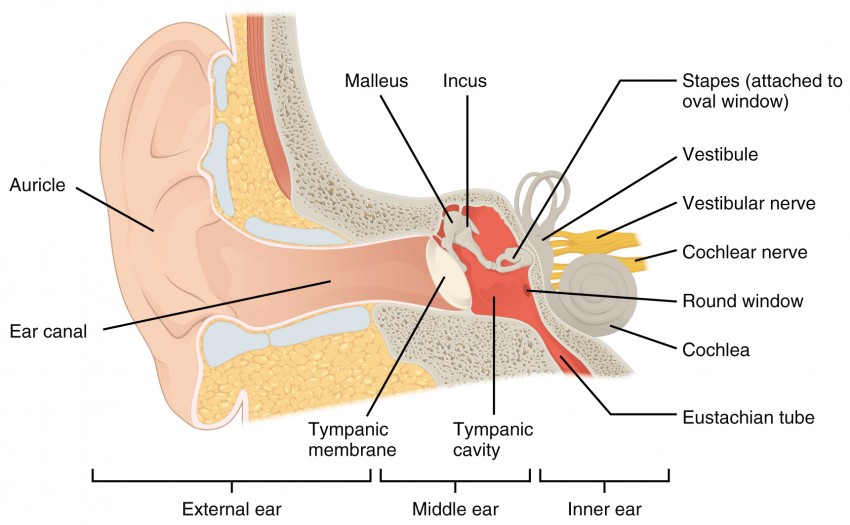

Hearing, or audition, is the transduction of sound waves into a neural signal that is made possible by the structures of the ear (Figure 1). The large, fleshy structure on the lateral aspect of the head is known as the auricle. Some sources will also refer to this structure as the pinna, though that term is more appropriate for a structure that can be moved, such as the external ear of a cat. The C-shaped curves of the auricle direct sound waves toward the auditory canal. The canal enters the skull through the external auditory meatus of the temporal bone. At the end of the auditory canal is the tympanic membrane, or ear drum, which vibrates after it is struck by sound waves. The auricle, ear canal, and tympanic membrane are often referred to as the external ear.

The middle ear consists of a space spanned by three small bones called the ossicles. The three ossicles are the malleus, incus, and stapes, which are Latin names that roughly translate to hammer, anvil, and stirrup. The malleus is attached to the tympanic membrane and articulates with the incus. The incus, in turn, articulates with the stapes. The stapes is then attached to the inner ear, where the sound waves will be transduced into a neural signal. The middle ear is connected to the pharynx through the Eustachian tube, which helps equilibrate air pressure across the tympanic membrane. The tube is normally closed but will pop open when the muscles of the pharynx contract during swallowing or yawning.

Figure 1. Structures of the Ear The external ear contains the auricle, ear canal, and tympanic membrane. The middle ear contains the ossicles and is connected to the pharynx by the Eustachian tube. The inner ear contains the cochlea and vestibule, which are responsible for audition and equilibrium, respectively.

The inner ear is often described as a bony labyrinth, as it is composed of a series of canals embedded within the temporal bone. It has two separate regions, the cochlea and the vestibule, which are responsible for hearing and balance, respectively. The neural signals from these two regions are relayed to the brain stem through separate fiber bundles. However, these two distinct bundles travel together from the inner ear to the brain stem as the vestibulocochlear nerve. Sound is transduced into neural signals within the cochlear region of the inner ear, which contains the sensory neurons of the spiral ganglia. These ganglia are located within the spiral-shaped cochlea of the inner ear. The cochlea is attached to the stapes through the oval window. The oval window is located at the beginning of a fluid-filled tube within the cochlea called the scala vestibuli. The scala vestibuli extends from the oval window, travelling above the cochlear duct, which is the central cavity of the cochlea that contains the sound-transducing neurons.

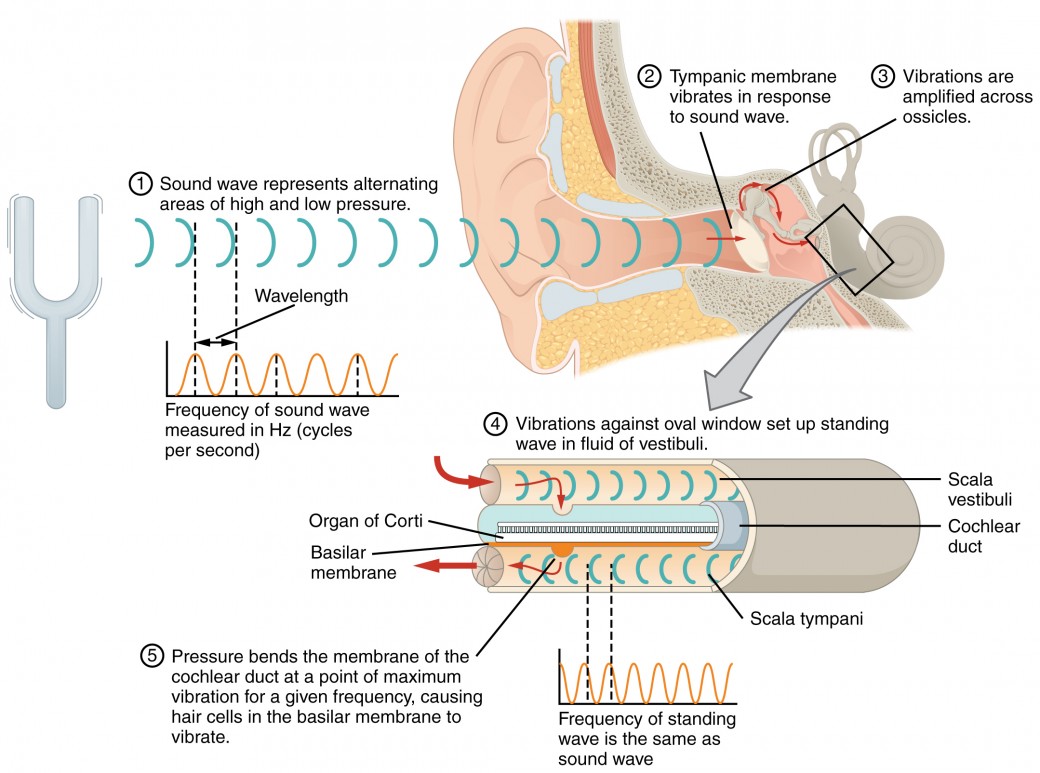

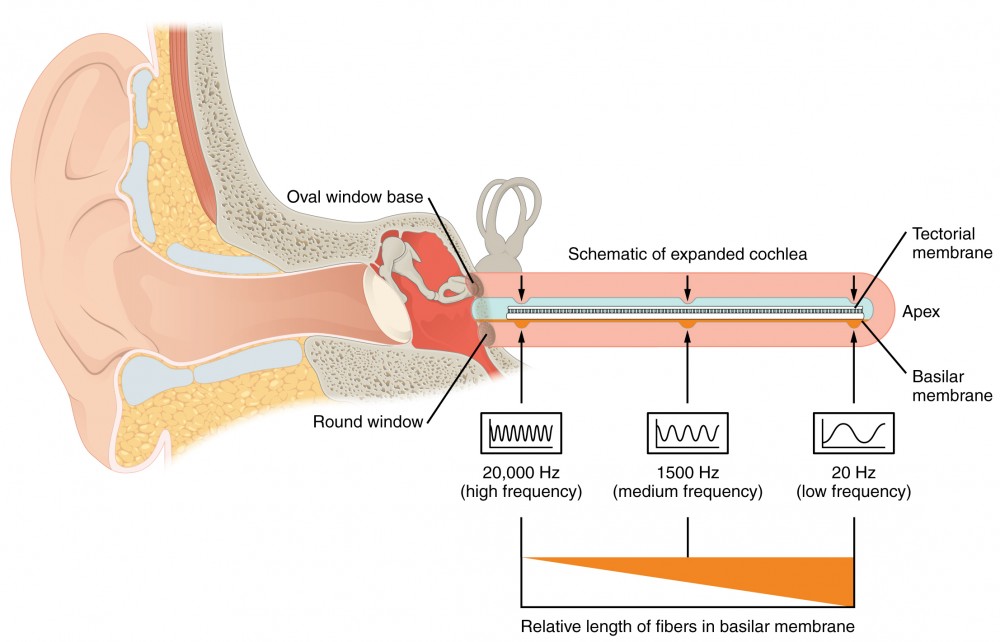

At the uppermost tip of the cochlea, the scala vestibuli curves over the top of the cochlear duct. The fluid-filled tube, now called the scala tympani, returns to the base of the cochlea, this time travelling under the cochlear duct. The scala tympani ends at the round window, which is covered by a membrane that contains the fluid within the scala. As vibrations of the ossicles travel through the oval window, the fluid of the scala vestibuli and scala tympani moves in a wave-like motion. The frequency of the fluid waves match the frequencies of the sound waves (Figure 2). The membrane covering the round window will bulge out or pucker in with the movement of the fluid within the scala tympani.

Figure 2. Transmission of Sound Waves to Cochlea A sound wave causes the tympanic membrane to vibrate. This vibration is amplified as it moves across the malleus, incus, and stapes. The amplified vibration is picked up by the oval window causing pressure waves in the fluid of the scala vestibuli and scala tympani. The complexity of the pressure waves is determined by the changes in amplitude and frequency of the sound waves entering the ear.

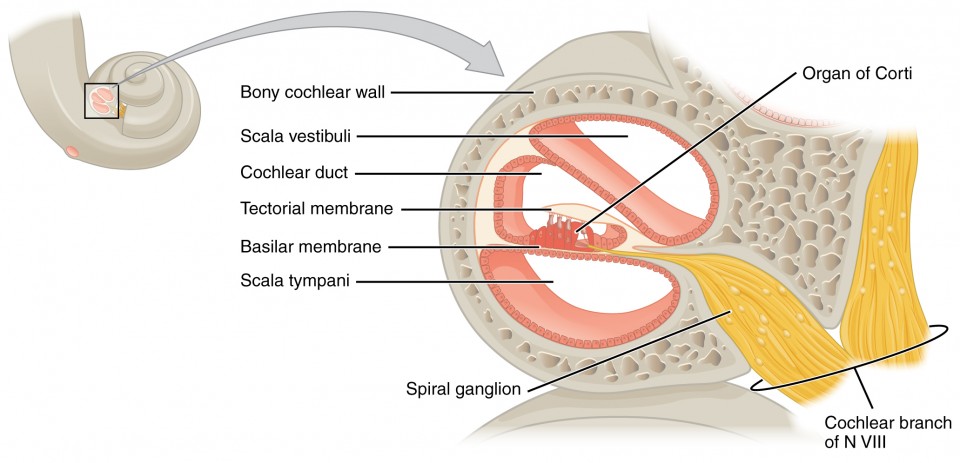

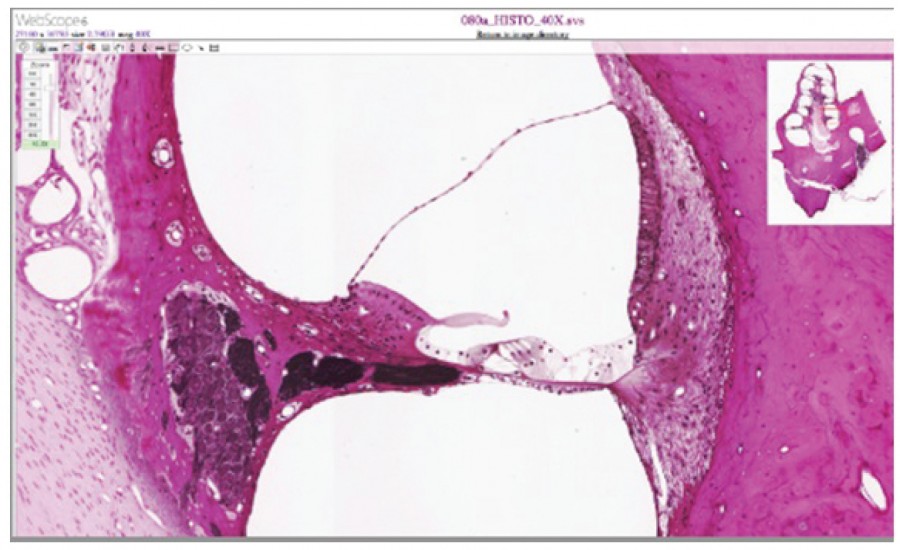

A cross-sectional view of the cochlea shows that the scala vestibuli and scala tympani run along both sides of the cochlear duct (Figure 3. The cochlear duct contains several organs of Corti, which tranduce the wave motion of the two scala into neural signals. The organs of Corti lie on top of the basilar membrane, which is the side of the cochlear duct located between the organs of Corti and the scala tympani. As the fluid waves move through the scala vestibuli and scala tympani, the basilar membrane moves at a specific spot, depending on the frequency of the waves. Higher frequency waves move the region of the basilar membrane that is close to the base of the cochlea. Lower frequency waves move the region of the basilar membrane that is near the tip of the cochlea.

Figure 3. Cross Section of the Cochlea The three major spaces within the cochlea are highlighted. The scala tympani and scala vestibuli lie on either side of the cochlear duct. The organ of Corti, containing the mechanoreceptor hair cells, is adjacent to the scala tympani, where it sits atop the basilar membrane.

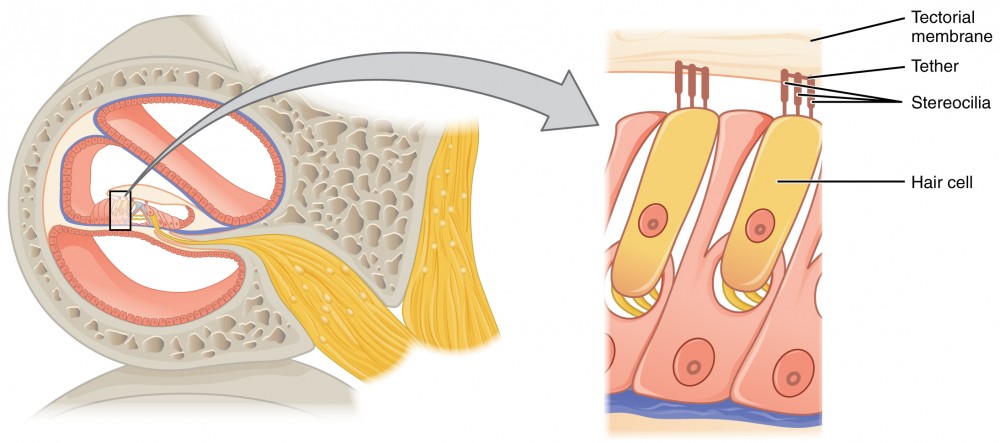

The organs of Corti contain hair cells, which are named for the hair-like stereocilia extending from the cell’s apical surfaces (Figure 4). The stereocilia are an array of microvilli-like structures arranged from tallest to shortest. Protein fibers tether adjacent hairs together within each array, such that the array will bend in response to movements of the basilar membrane. The stereocilia extend up from the hair cells to the overlying tectorial membrane, which is attached medially to the organ of Corti. When the pressure waves from the scala move the basilar membrane, the tectorial membrane slides across the stereocilia. This bends the stereocilia either toward or away from the tallest member of each array.

When the stereocilia bend toward the tallest member of their array, tension in the protein tethers opens ion channels in the hair cell membrane. This will depolarize the hair cell membrane, triggering nerve impulses that travel down the afferent nerve fibers attached to the hair cells. When the stereocilia bend toward the shortest member of their array, the tension on the tethers slackens and the ion channels close. When no sound is present, and the stereocilia are standing straight, a small amount of tension still exists on the tethers, keeping the membrane potential of the hair cell slightly depolarized.

Figure 4. Hair Cell The hair cell is a mechanoreceptor with an array of stereocilia emerging from its apical surface. The stereocilia are tethered together by proteins that open ion channels when the array is bent toward the tallest member of their array, and closed when the array is bent toward the shortest member of their array.

Figure 5. Cochlea and Organ of Corti LM × 412. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

As stated above, a given region of the basilar membrane will only move if the incoming sound is at a specific frequency. Because the tectorial membrane only moves where the basilar membrane moves, the hair cells in this region will also only respond to sounds of this specific frequency. Therefore, as the frequency of a sound changes, different hair cells are activated all along the basilar membrane.

The cochlea encodes auditory stimuli for frequencies between 20 and 20,000 Hz, which is the range of sound that human ears can detect. The unit of Hertz measures the frequency of sound waves in terms of cycles produced per second. Frequencies as low as 20 Hz are detected by hair cells at the apex, or tip, of the cochlea. Frequencies in the higher ranges of 20 KHz are encoded by hair cells at the base of the cochlea, close to the round and oval windows (Figure 6). Most auditory stimuli contain a mixture of sounds at a variety of frequencies and intensities (represented by the amplitude of the sound wave). The hair cells along the length of the cochlear duct, which are each sensitive to a particular frequency, allow the cochlea to separate auditory stimuli by frequency, just as a prism separates visible light into its component colors.

Figure 6. Frequency Coding in the Cochlea The standing sound wave generated in the cochlea by the movement of the oval window deflects the basilar membrane on the basis of the frequency of sound. Therefore, hair cells at the base of the cochlea are activated only by high frequencies, whereas those at the apex of the cochlea are activated only by low frequencies.

Watch this video to learn more about how the structures of the ear convert sound waves into a neural signal by moving the “hairs,” or stereocilia, of the cochlear duct. Specific locations along the length of the duct encode specific frequencies, or pitches. The brain interprets the meaning of the sounds we hear as music, speech, noise, etc.

Which ear structures are responsible for the amplification and transfer of sound from the external ear to the inner ear?

Watch this animation to learn more about the inner ear and to see the cochlea unroll, with the base at the back of the image and the apex at the front.

Specific wavelengths of sound cause specific regions of the basilar membrane to vibrate, much like the keys of a piano produce sound at different frequencies. Based on the animation, where do frequencies—from high to low pitches—cause activity in the hair cells within the cochlear duct?

Equilibrium (Balance)

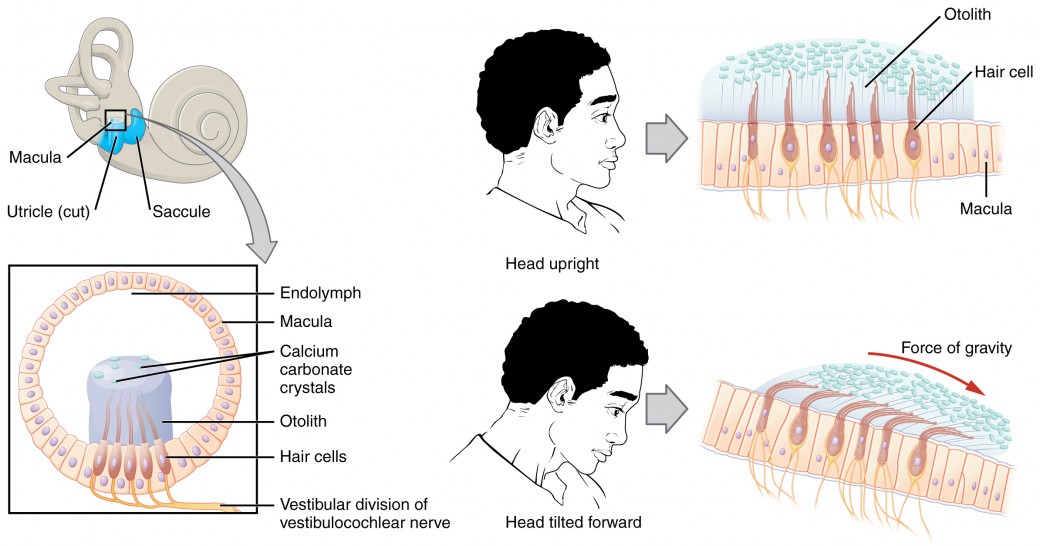

Along with audition, the inner ear is responsible for encoding information about equilibrium, the sense of balance. A similar mechanoreceptor—a hair cell with stereocilia—senses head position, head movement, and whether our bodies are in motion. These cells are located within the vestibule of the inner ear. Head position is sensed by the utricle and saccule, whereas head movement is sensed by the semicircular canals. The neural signals generated in the vestibular ganglion are transmitted through the vestibulocochlear nerve to the brain stem and cerebellum. The utricle and saccule are both largely composed of macula tissue (plural = maculae). The macula is composed of hair cells surrounded by support cells. The stereocilia of the hair cells extend into a viscous gel called the otolith (Figure 7).

The otolith contains calcium carbonate crystals, making it denser and giving it greater inertia than the macula. Therefore, gravity will cause the otolith to move separately from the macula in response to head movements. Tilting the head causes the otolith to slide over the macula in the direction of gravity. The moving otolith layer, in turn, bends the sterocilia to cause some hair cells to depolarize as others hyperpolarize. The exact tilt of the head is interpreted by the brain on the basis of the pattern of hair-cell depolarization.

Figure 7. Linear Acceleration Coding by Maculae The maculae are specialized for sensing linear acceleration, such as when gravity acts on the tilting head, or if the head starts moving in a straight line. The difference in inertia between the hair cell stereocilia and the otolith in which they are embedded leads to a shearing force that causes the stereocilia to bend in the direction of that linear acceleration.

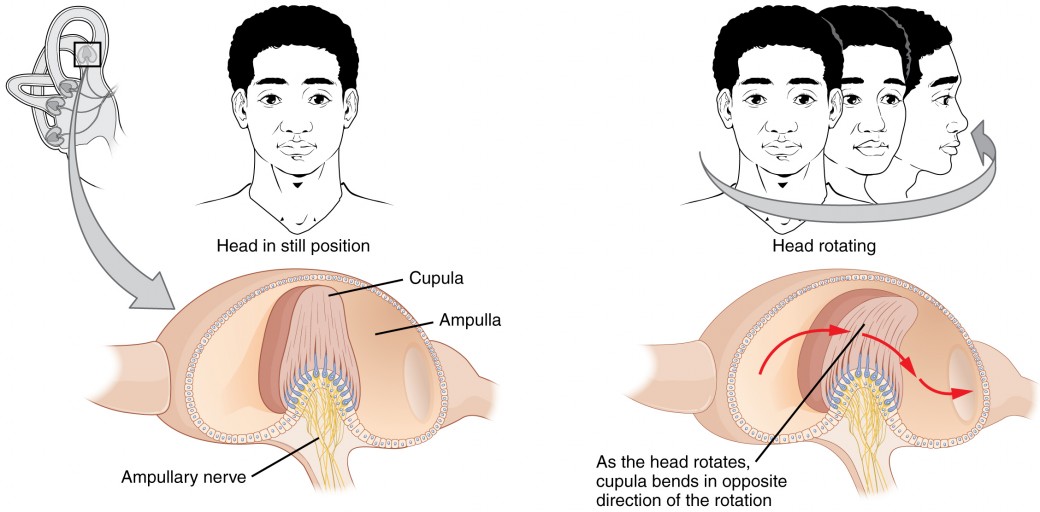

The semicircular canals are three ring-like extensions of the vestibule. One is oriented in the horizontal plane, whereas the other two are oriented in the vertical plane. The anterior and posterior vertical canals are oriented at approximately 45 degrees relative to the sagittal plane (Figure 8).

The base of each semicircular canal, where it meets with the vestibule, connects to an enlarged region known as the ampulla. The ampulla contains the hair cells that respond to rotational movement, such as turning the head while saying “no.” The stereocilia of these hair cells extend into the cupula, a membrane that attaches to the top of the ampulla. As the head rotates in a plane parallel to the semicircular canal, the fluid lags, deflecting the cupula in the direction opposite to the head movement. The semicircular canals contain several ampullae, with some oriented horizontally and others oriented vertically. By comparing the relative movements of both the horizontal and vertical ampullae, the vestibular system can detect the direction of most head movements within three-dimensional (3-D) space.

Figure 8. Rotational Coding by Semicircular Canals Rotational movement of the head is encoded by the hair cells in the base of the semicircular canals. As one of the canals moves in an arc with the head, the internal fluid moves in the opposite direction, causing the cupula and stereocilia to bend. The movement of two canals within a plane results in information about the direction in which the head is moving, and activation of all six canals can give a very precise indication of head movement in three dimensions.

Information Pathways for the Inner Ear

The sensory pathway for audition travels along the vestibulocochlear nerve, which synapses with neurons in the cochlear nuclei of the superior medulla. Within the brain stem, input from either ear is combined to extract location information from the auditory stimuli. Whereas the initial auditory stimuli received at the cochlea strictly represent the frequency—or pitch—of the stimuli, the locations of sounds can be determined by comparing information arriving at both ears.

Sound localization is a feature of central processing in the auditory nuclei of the brain stem. Sound localization is achieved by the brain calculating the interaural time difference and the interaural intensity difference. A sound originating from a specific location will arrive at each ear at different times, unless the sound is directly in front of the listener. If the sound source is slightly to the left of the listener, the sound will arrive at the left ear microseconds before it arrives at the right ear (Figure 2). This time difference is an example of an interaural time difference. Also, the sound will be slightly louder in the left ear than in the right ear because some of the sound waves reaching the opposite ear are blocked by the head. This is an example of an interaural intensity difference.

Figure 2. Auditory Brain Stem Mechanisms of Sound Localization. Localizing sound in the horizontal plane is achieved by processing in the medullary nuclei of the auditory system. Connections between neurons on either side are able to compare very slight differences in sound stimuli that arrive at either ear and represent interaural time and intensity differences.

Auditory processing continues on to a nucleus in the midbrain called the inferior colliculus. Axons from the inferior colliculus project to two locations, the thalamus and the superior colliculus. The medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus receives the auditory information and then projects that information to the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex. The superior colliculus receives input from the visual and somatosensory systems, as well as the ears, to initiate stimulation of the muscles that turn the head and neck toward the auditory stimulus.

Balance is coordinated through the vestibular system, the nerves of which are composed of axons from the vestibular ganglion that carries information from the utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals. The system contributes to controlling head and neck movements in response to vestibular signals. An important function of the vestibular system is coordinating eye and head movements to maintain visual attention. Most of the axons terminate in the vestibular nuclei of the medulla. Some axons project from the vestibular ganglion directly to the cerebellum, with no intervening synapse in the vestibular nuclei. The cerebellum is primarily responsible for initiating movements on the basis of equilibrium information.

Neurons in the vestibular nuclei project their axons to targets in the brain stem. One target is the reticular formation, which influences respiratory and cardiovascular functions in relation to body movements. A second target of the axons of neurons in the vestibular nuclei is the spinal cord, which initiates the spinal reflexes involved with posture and balance. To assist the visual system, fibers of the vestibular nuclei project to the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nuclei to influence signals sent along the cranial nerves. These connections constitute the pathway of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), which compensates for head and body movement by stabilizing images on the retina (Figure 3). Finally, the vestibular nuclei project to the thalamus to join the proprioceptive pathway of the dorsal column system, allowing conscious perception of equilibrium.

Figure 3. Vestibulo-ocular Reflex. Connections between the vestibular system and the cranial nerves controlling eye movement keep the eyes centered on a visual stimulus, even though the head is moving. During head movement, the eye muscles move the eyes in the opposite direction as the head movement, keeping the visual stimulus centered in the field of view.

Candela Citations

- Anatomy & Physiology. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@9.1. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@9.1