Introduction

Ocean water is constantly in motion: north-south, east-west, alongshore, and vertically. Seawater motions are the result of waves, tides, and currents (Figure below). Ocean movements are the consequence of many separate factors: wind, tides, Coriolis effect, water density differences, and the shape of the ocean basins. Water movements and their causes will be discussed in this lesson.

Waves

Waves have been discussed in previous chapters in several contexts: seismic waves traveling through the planet, sound waves traveling through seawater, and ocean waves eroding beaches. Waves transfer energy and the size of a wave and the distance it travels depends on the amount of energy that it carries.

Wind Waves

This lesson studies the most familiar waves, those on the ocean’s surface. Ocean waves originate from wind blowing – steady winds or high storm winds – over the water. Sometimes these winds are far from where the ocean waves are seen. What factors create the largest ocean waves?

The largest wind waves form when the wind

- is very strong

- blows steadily for a long time

- blows over a long distance

The wind could be strong, but if it gusts for just a short time, large waves won’t form.

Wind blowing across the water transfers energy to that water. The energy first creates tiny ripples that create an uneven surface for the wind to catch so that it may create larger waves. These waves travel across the ocean out of the area where the wind is blowing.

Remember that a wave is a transfer of energy. Do you think the same molecules of water that starts out in a wave in the middle of the ocean later arrive at the shore?

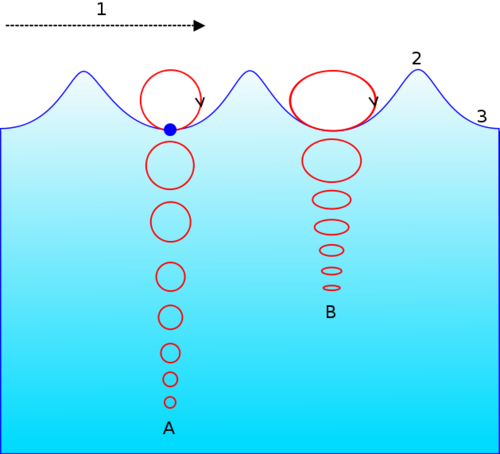

Water molecules in waves make circles or ellipses (Figure below). Energy transfers between molecules but the molecules themselves mostly bob up and down in place.

In this animation, a water bottle bobs in place like a water molecule: http://www.onr.navy.mil/focus/ocean/motion/waves1.htm

An animation of motion in wind waves from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography:http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/earthguide/diagrams/waves/swf/wave_wind.html

The circles show the motion of a water molecule in a wind wave. Wave energy is greatest at the surface and decreases with depth. A shows that a water molecule travels in a circular motion in deep water. B shows that molecules in shallow water travel in an elliptical path because of the ocean bottom.

An animation of a deep water wave is seen here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Deep_water_wave.gif.

An animation of a shallow water wave is seen here: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shallow_water_wave.gif.

When does a wave break? Do waves only break when they reach shore? Waves break when they become too tall to be supported by their base. This can happen at sea but happens predictably as a wave moves up a shore. The energy at the bottom of the wave is lost by friction with the ground so that the bottom of the wave slows down but the top of the wave continues at the same speed. The crest falls over and crashes down.

Local Surface Currents

The surface currents described above are all large and unchanging. Local surface currents are also found along shorelines (Figure below). Two are longshore currents and rip currents.

Longshore currents move water and sediment parallel to the shore in the direction of the prevailing local winds.

Rip currents are potentially dangerous currents that carry large amounts of water offshore quickly. Look at the rip-current animation to determine what to do if you are caught in a rip current: http://www.onr.navy.mil/focus/ocean/motion/currents2.htm. Each summer in the United States at least a few people die when they are caught in rip currents.

This animation shows the surface currents in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean off of the southeastern United States:http://polar.ncep.noaa.gov/ofs/viewer.shtml?-gulfmex-cur-0-large-rundate=latest.

Wave Action and Erosion

Have you ever been to visit a beach? Some beaches have large, strong rolling waves that rise up and collapse as they crash into the shore. All waves are energy traveling through some type of material (Figure 10.13). The waves that we are most familiar with travel through water. Most of these waves form from wind blowing over the water; sometimes steady winds that blow and sometimes from a storm that forms over the water. The energy of waves does the work of erosion when a wave reaches the shore. When you find a piece of frosted glass along a beach, you have found some evidence of the work of waves. What other evidence might you find?

As wind blows over the surface of the water, it disturbs the water, producing the familiar shape of a wave. You can see this shape in Figure 10.14. The highest part of a wave is called the wave crest. The lowest part is called the wave trough. The vertical distance from the highest part of a wave to the lowest is called the wave height. The horizontal distance between one wave crest and the next crest, is called the wavelength. Three things influence how big a wave might get. If the wind is very strong, and it blows steadily for a long time over a long distance, the very largest waves will form. The wind could be strong, but if it gusts for just a short time, large waves won’t form. Bigger waves do more work of erosion which changes our shorelines. Each day that waves break along the shore, they steadily erode away a minute bit of the shoreline. When one day, a really big storm like a hurricane arrives, it will do a lot of damage in just a very short time.

As waves come into shore, they usually reach the shore at some angle. This means one part of the wave reaches shallow water sooner than the parts of the wave that are further out. As a wave comes into shore, the water ‘feels’ the bottom which slows down the wave. So the shallower parts of the wave slow down more than the parts that are further from the shore. This makes the wave ‘bend’, which is called refraction. The way that waves bend as they come into shore either concentrates wave energy or disperses it. In quiet water areas like bays, wave energy is dispersed and sand gets deposited. Areas like cliffs that stick out into the water, are eroded away by the strong wave energy that concentrates its power on the cliff (Figure 10.15).

Wave-cut cliffs form where waves cut into the bottom part of the cliff, eroding away the soil and rocks there. First the waves cut a notch into the base of the cliff. If enough material is cut away, the cliff above can collapse into the water. Many years of this type of erosion can form a wave-cut platform (Figure 10.16).

If waves erode a cliff from two sides, the erosion produced can form an open area in the cliff called an arch (Figure 10.17). If the material above the arch eventually erodes away, a piece of tall rock can remain in the water, which is called a sea stack (Figure 10.18).

Wave Deposition

Rivers carry the sand that comes from erosion of mountains and land areas of the continents to the shore. Soil and rock are also eroded from cliffs and shorelines by waves. That material is transported by waves and deposited in quieter water areas. As the waves come onto shore and break, water and particles move along the shore. When lots of sand accumulates in one place, it forms a beach. Beaches can be made of mineral grains, like quartz, but beaches can also be made of pieces of shell or coral or even bits of broken hardened lava (Figure 10.19).

Waves continually move sand grains along the shore. Smaller particles like silt and clay don’t get deposited at the shore because the water here is too turbulent. The work of waves moves sand from the beaches on shore to bars of sand offshore as the seasons change. In the summer time, waves of lower energy bring sand up onto the beach and leave it there. That is good for the many people who enjoy sitting on soft sand when they visit the beach (Figure 10.20). In the wintertime, waves and storms of higher energy bring the sand from the beach back offshore. If you visit your favorite beach in the wintertime, you will find a steeper, rockier beach than the flat, sandy beach of summer. Some communities truck in sand to resupply sand to beaches. It is very important to study the energy of the waves and understand the types of sand particles that normally make up the beach before spending lots of money to do this. If the sand that is trucked in has pieces that are small enough to be carried away by the waves on that beach, the sand will be gone in a very short time.

Sand transported by the work of waves breaking along the shore can form sand bars that stretch across a bay or ridges of sand that extend away from the shore, called spits. Sometimes the end of a spit hooks around towards the quieter waters of the bay as waves refract, causing the sand to curve around in the shape of a hook.

When the land that forms the shore is relatively flat and gently sloping, the shoreline may be lined with long narrow islands called barrier islands (Figure 10.21). Most barrier islands are just a few kilometers wide and tens of kilometers long. Many famous beaches, like Miami Beach, are barrier islands. In its natural state, a barrier island acts as the first line of defense against storms like hurricanes.

Instead of keeping barrier islands natural, these areas end up being some of the most built up, urbanized areas of our coastlines. That means storms, like hurricanes, damage houses and businesses rather than hitting soft, vegetated sandy areas. Some hurricanes have hit barrier islands so hard that they break right through the island, removing sand, houses and anything in the way.

Protecting Shorelines

Humans build several different types of structures to try to slow down the regular work of erosion that waves produce and to help prevent damage to homes from large storms. One structure that people build, called a groyne (or groin), is a long narrow pile of rocks that extends out into the water, at right angles to the shoreline (Figure 10.22). The groyne traps sand on one side of the groyne, keeping the sand there, rather than allowing it to move along the coastline. This works well for the person who is on the upcurrent side of the groyne, but it causes problems for the people on the opposite, downcurrent side. Those people no longer have sand reaching the areas in front of their homes. What happens as a result is that people must build another groyne to trap sand there. This means lots of people build groynes, but it is not a very good answer to the problem of wave erosion.

Some other structures that people build include breakwaters and sea walls (Figure 10.23). Both of these are built parallel to the shoreline. A breakwater is built out away from the shore in the water while a sea wall is built right along the shore. Breakwaters are built in bay areas to help keep boats safe from the energy of breaking waves. Sometimes enough sand deposits in these quiet water areas that people then need to work to remove the sand. Sea walls are built to protect beach houses from waves during severe storms. If the waves in a storm are very large, sometimes they erode away the whole sea wall, leaving the area unprotected entirely. People do not always want to choose safe building practices, and instead choose to build a beach house right on the beach. If you want your beach house to stay in good shape for many years, it is smarter to build your house away from the shore.

Lesson Summary

- Waves in the ocean are what we see as energy travels through the water.

- The energy of waves produces erosional formations like cliffs, wave cut platforms, sea arches, and sea stacks.

- When waves reach the shore, deposits like beaches, spits, and barrier islands form in certain areas.

- Groynes, jetties, breakwaters, and sea walls are structures humans build to protect the shore from the erosion of breaking waves.

Review Questions

- Name three structures that people build to try to prevent wave erosion.

- Name three natural landforms that are produced by wave erosion.

- What are the names of the parts of a waveform?

- Describe the process that produces wave refraction.

- If you were to visit a beach in a tropical area with coral reefs, what would the beach there be made of?

Vocabulary

- arch

- An erosional landform that is produced when waves erode through a cliff.

- barrier island

- Long, narrow island, usually composed of sand that serves as nature’s first line of defense against storms.

- breakwater

- Structure built in the water, parallel to the shore to protect boats or harbor areas from strong waves.

- groyne

- Long, narrow piles of stone or timbers built perpendicular to the shore to trap sand.

- sea stack

- Isolated tower of rock that forms when a sea arch collapses.

- sea wall

- Structure built along the shore, parallel to the shore, to protect against strong waves.

- spit

- Long, narrow bar of sand that forms as waves transport sand along shore.

- wave-cut platform

- Flat, level area formed by wave erosion as waves undercut cliffs.

- wave crest

- The highest part of a wave form.

- wave height

- The vertical distance from wave crest to wave trough.

- wavelength

- The horizontal distance from wave crest to wave crest.

- wave trough

- The lowest part of a wave form.

Points to Consider

- What situations would increase the rate of erosion by waves?

- If barrier islands are nature’s first line of defense against ocean storms, why do people build on them?

- Could a sea wall ever increase the amount of damage done by waves?

Candela Citations

- Provided by: CK12.org. Located at: http://www.ck12.org/book/CK-12-Earth-Science-For-High-School/section/14.2/. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial