What you’ll learn to do: explain symptoms and potential causes of schizophrenic and dissociative disorders

Schizophrenia is a severe disorder characterized by a complete breakdown in one’s ability to function in life; it often requires hospitalization. People with schizophrenia experience hallucinations and delusions, and they have extreme difficulty regulating their emotions and behavior. Thinking is incoherent and disorganized, behavior is extremely bizarre, emotions are flat, and motivation to engage in most basic life activities is lacking.

Schizophrenia is not to be confused with multiple personality disorder, which is technically termed dissociative identity disorder. The main characteristic of dissociative disorders is that people become dissociated from their sense of self, resulting in memory and identity disturbances. Dissociative disorders listed in the DSM-5 include dissociative amnesia, depersonalization/derealization disorder, and dissociative identity disorder. A person with dissociative amnesia is unable to recall important personal information, often after a stressful or traumatic experience. In this section, you’ll learn about the differences between schizophrenia and these disorders.

Learning Objectives

- Categorize and describe the major symptoms of schizophrenia

- Describe the interplay between genetic, biological, and environmental factors that are associated with the development of schizophrenia

- Identify and differentiate the symptoms and potential causes of dissociative amnesia, depersonalization/ derealization disorder, and dissociative identity disorder

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychological disorder that is characterized by major disturbances in thought, perception, emotion, and behavior. About 1% of the population experiences schizophrenia in their lifetime, and usually the disorder is first diagnosed during early adulthood (early to mid-20s). Most people with schizophrenia experience significant difficulties in many day-to-day activities, such as holding a job, paying bills, caring for oneself (grooming and hygiene), and maintaining relationships with others. Frequent hospitalizations are more often the rule rather than the exception with schizophrenia. Even when they receive the best treatments available, many with schizophrenia will continue to experience serious social and occupational impairment throughout their lives.

What is schizophrenia? First, schizophrenia is not a condition involving a split personality; that is, schizophrenia is not the same thing as dissociative identity disorder (better known as multiple personality disorder). These disorders are sometimes confused because the word schizophrenia first coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911, derives from Greek words that refer to a “splitting” (schizo) of psychic functions (phrene) (Green, 2001).

Schizophrenia is considered a psychotic disorder, or one in which the person’s thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors are impaired to the point where she is not able to function normally in life. In informal terms, one who suffers from a psychotic disorder (that is, has a psychosis) is disconnected from the world in which most of us live.

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

The main symptoms of schizophrenia include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking, disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms (APA, 2013). A hallucination is a perceptual experience that occurs in the absence of external stimulation. Auditory hallucinations (hearing voices) occur in roughly two-thirds of patients with schizophrenia and are by far the most common form of hallucination (Andreasen, 1987). The voices may be familiar or unfamiliar, they may have a conversation or argue, or the voices may provide a running commentary on the person’s behavior (Tsuang, Farone, & Green, 1999).

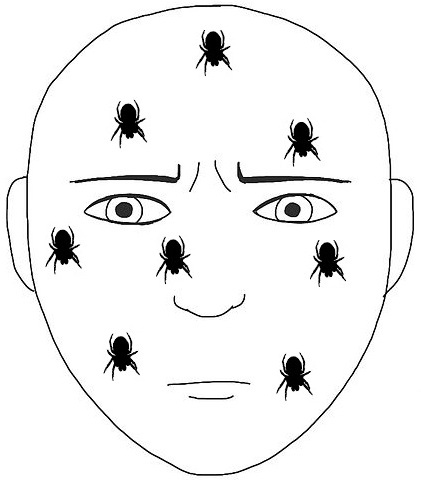

Figure 1. Tactile hallucinations, like that of imaginary spiders crawling on the skin, are another type of hallucination.

Less common are visual hallucinations (seeing things that are not there) and olfactory hallucinations (smelling odors that are not actually present).

Delusions are beliefs that are contrary to reality and are firmly held even in the face of contradictory evidence. Many of us hold beliefs that some would consider odd, but a delusion is easily identified because it is clearly absurd. A person with schizophrenia may believe that his mother is plotting with the FBI to poison his coffee, or that his neighbor is an enemy spy who wants to kill him. These kinds of delusions are known as paranoid delusions, which involve the (false) belief that other people or agencies are plotting to harm the person. People with schizophrenia also may hold grandiose delusions, beliefs that one holds special power, unique knowledge, or is extremely important. For example, the person who claims to be Jesus Christ, or who claims to have knowledge going back 5,000 years, or who claims to be a great philosopher is experiencing grandiose delusions. Other delusions include the belief that one’s thoughts are being removed (thought withdrawal) or thoughts have been placed inside one’s head (thought insertion). Another type of delusion is somatic delusion, which is the belief that something highly abnormal is happening to one’s body (e.g., that one’s kidneys are being eaten by cockroaches).

Disorganized thinking refers to disjointed and incoherent thought processes—usually detected by what a person says. The person might ramble, exhibit loose associations (jump from topic to topic), or talk in a way that is so disorganized and incomprehensible that it seems as though the person is randomly combining words. Disorganized thinking is also exhibited by blatantly illogical remarks (e.g., “Fenway Park is in Boston. I live in Boston. Therefore, I live at Fenway Park.”) and by tangentiality: responding to others’ statements or questions by remarks that are either barely related or unrelated to what was said or asked. For example, if a person diagnosed with schizophrenia is asked if she is interested in receiving special job training, she might state that she once rode on a train somewhere. To a person with schizophrenia, the tangential (slightly related) connection between job training and riding a train are sufficient enough to cause such a response.

Disorganized or abnormal motor behavior refers to unusual behaviors and movements: becoming unusually active, exhibiting silly child-like behaviors (giggling and self-absorbed smiling), engaging in repeated and purposeless movements, or displaying odd facial expressions and gestures. In some cases, the person will exhibit catatonic behaviors, which show decreased reactivity to the environment, such as posturing, in which the person maintains a rigid and bizarre posture for long periods of time, or catatonic stupor, a complete lack of movement and verbal behavior.

Schizophrenia has positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia are symptoms of commission, meaning they are something that individuals do or think. Examples include the hallucinations, delusions, and bizarre or disorganized behavior describe above. Negative symptoms are those that reflect noticeable decreases and absences in certain behaviors, emotions, or drives (Green, 2001). A person who exhibits diminished emotional expression shows no emotion in his facial expressions, speech, or movements, even when such expressions are normal or expected (also known as flat affect). Avolition is characterized by a lack of motivation to engage in self-initiated and meaningful activity, including the most basic of tasks, such as bathing and grooming. Alogia refers to reduced speech output; in simple terms, patients do not say much. Another negative symptom is asociality, or social withdrawal and lack of interest in engaging in social interactions with others. A final negative symptom, anhedonia, refers to an inability to experience pleasure. One who exhibits anhedonia expresses little interest in what most people consider to be pleasurable activities, such as hobbies, recreation, or sexual activity.

Link to Learning

Watch this video and try to identify which classic symptoms of schizophrenia are shown.

Try It

Causes of Schizophrenia

Genes

When considering the role of genetics in schizophrenia, as in any disorder, conclusions based on family and twin studies are subject to criticism. This is because family members who are closely related (such as siblings) are more likely to share similar environments than are family members who are less closely related (such as cousins); further, identical twins may be more likely to be treated similarly by others than might fraternal twins. Thus, family and twin studies cannot completely rule out the possible effects of shared environments and experiences. Such problems can be corrected by using adoption studies, in which children are separated from their parents at an early age. One of the first adoption studies of schizophrenia conducted by Heston (1966) followed 97 adoptees, including 47 who were born to mothers with schizophrenia, over a 36-year period. Five of the 47 adoptees (11%) whose mothers had schizophrenia were later diagnosed with schizophrenia, compared to none of the 50 control adoptees. Other adoption studies have consistently reported that for adoptees who are later diagnosed with schizophrenia, their biological relatives have a higher risk of schizophrenia than do adoptive relatives (Shih, Belmonte, & Zandi, 2004).

Although adoption studies have supported the hypothesis that genetic factors contribute to schizophrenia, they have also demonstrated that the disorder most likely arises from a combination of genetic and environmental factors, rather than just genes themselves. For example, investigators in one study examined the rates of schizophrenia among 303 adoptees (Tienari et al., 2004). A total of 145 of the adoptees had biological mothers with schizophrenia; these adoptees constituted the high genetic risk group. The other 158 adoptees had mothers with no psychiatric history; these adoptees composed the low genetic risk group. The researchers managed to determine whether the adoptees’ families were either healthy or disturbed. For example, the adoptees were considered to be raised in a disturbed family environment if the family exhibited a lot of criticism, conflict, and a lack of problem-solving skills. The findings revealed that adoptees whose mothers had schizophrenia (high genetic risk) and who had been raised in a disturbed family environment were much more likely to develop schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder (36.8%) than were adoptees whose biological mothers had schizophrenia but who had been raised in a healthy environment (5.8%), or than adoptees with a low genetic risk who were raised in either a disturbed (5.3%) or healthy (4.8%) environment. Because the adoptees who were at high genetic risk were likely to develop schizophrenia only if they were raised in a disturbed home environment, this study supports a diathesis-stress interpretation of schizophrenia—both genetic vulnerability and environmental stress are necessary for schizophrenia to develop, genes alone do not show the complete picture.

Neurotransmitters

If we accept that schizophrenia is at least partly genetic in origin, as it seems to be, it makes sense that the next step should be to identify biological abnormalities commonly found in people with the disorder. Perhaps not surprisingly, a number of neurobiological factors have indeed been found to be related to schizophrenia. One such factor that has received considerable attention for many years is the neurotransmitter dopamine. Interest in the role of dopamine in schizophrenia was stimulated by two sets of findings: drugs that increase dopamine levels can produce schizophrenia-like symptoms, and medications that block dopamine activity reduce the symptoms (Howes & Kapur, 2009). The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia proposed that an overabundance of dopamine or too many dopamine receptors are responsible for the onset and maintenance of schizophrenia (Snyder, 1976). More recent work in this area suggests that abnormalities in dopamine vary by brain region and thus contribute to symptoms in unique ways. In general, this research has suggested that an overabundance of dopamine in the limbic system may be responsible for some symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, whereas low levels of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex might be responsible primarily for the negative symptoms (avolition, alogia, asociality, and anhedonia) (Davis, Kahn, Ko, & Davidson, 1991). In recent years, serotonin has received attention, and newer antipsychotic medications used to treat the disorder work by blocking serotonin receptors (Baumeister & Hawkins, 2004).

Brain Anatomy

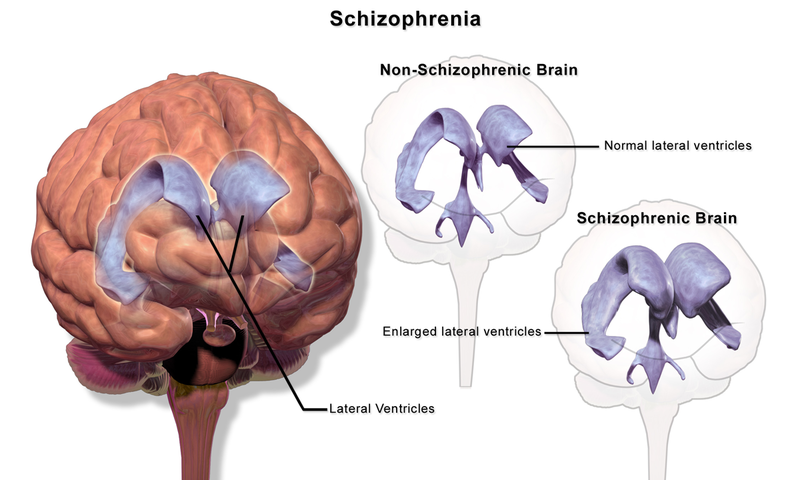

Brain imaging studies reveal that people with schizophrenia have enlarged ventricles, the cavities within the brain that contain cerebral spinal fluid (Green, 2001). This finding is important because larger than normal ventricles suggests that various brain regions are reduced in size, thus implying that schizophrenia is associated with a loss of brain tissue. In addition, many people with schizophrenia display a reduction in gray matter (cell bodies of neurons) in the frontal lobes (Lawrie & Abukmeil, 1998), and many show less frontal lobe activity when performing cognitive tasks (Buchsbaum et al., 1990). The frontal lobes are important in a variety of complex cognitive functions, such as planning and executing behavior, attention, speech, movement, and problem solving. Hence, abnormalities in this region provide merit in explaining why people with schizophrenia experience deficits in these of areas.

Events During Pregnancy

Why do people with schizophrenia have these brain abnormalities? A number of environmental factors that could impact normal brain development might be at fault. High rates of obstetric complications in the births of children who later developed schizophrenia have been reported (Cannon, Jones, & Murray, 2002). In addition, people are at an increased risk for developing schizophrenia if their mother was exposed to influenza during the first trimester of pregnancy (Brown et al., 2004). Research has also suggested that a mother’s emotional stress during pregnancy may increase the risk of schizophrenia in offspring. One study reported that the risk of schizophrenia is elevated substantially in offspring whose mothers experienced the death of a relative during the first trimester of pregnancy (Khashan et al., 2008).

Marijuana

Another variable that is linked to schizophrenia is marijuana use. Although a number of reports have shown that individuals with schizophrenia are more likely to use marijuana than are individuals without schizophrenia (Thornicroft, 1990), such investigations cannot determine if marijuana use leads to schizophrenia, or vice versa. However, a number of longitudinal studies have suggested that marijuana use is, in fact, a risk factor for schizophrenia. A classic investigation of over 45,000 Swedish conscripts who were followed up after 15 years found that those individuals who had reported using marijuana at least once by the time of conscription were more than 2 times as likely to develop schizophrenia during the ensuing 15 years than were those who reported never using marijuana; those who had indicated using marijuana 50 or more times were 6 times as likely to develop schizophrenia (Andréasson, Allbeck, Engström, & Rydberg, 1987). More recently, a review of 35 longitudinal studies found a substantially increased risk of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in people who had used marijuana, with the greatest risk in the most frequent users (Moore et al., 2007). Other work has found that marijuana use is associated with an onset of psychotic disorders at an earlier age (Large, Sharma, Compton, Slade, & Nielssen, 2011). Overall, the available evidence seems to indicate that marijuana use plays a causal role in the development of schizophrenia, although it is important to point out that marijuana use is not an essential or sufficient risk factor as not all people with schizophrenia have used marijuana and the majority of marijuana users do not develop schizophrenia (Casadio, Fernandes, Murray, & Di Forti, 2011). One plausible interpretation of the data is that early marijuana use may disrupt normal brain development during important early maturation periods in adolescence (Trezza, Cuomo, & Vanderschuren, 2008). Thus, early marijuana use may set the stage for the development of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, especially among individuals with an established vulnerability (Casadio et al., 2011).

Schizophrenia: Early Warning Signs

Early detection and treatment of conditions such as heart disease and cancer have improved survival rates and quality of life for people who suffer from these conditions. A new approach involves identifying people who show minor symptoms of psychosis, such as unusual thought content, paranoia, odd communication, delusions, problems at school or work, and a decline in social functioning—which are coined prodromal symptoms—and following these individuals over time to determine which of them develop a psychotic disorder and which factors best predict such a disorder. A number of factors have been identified that predict a greater likelihood that prodromal individuals will develop a psychotic disorder: genetic risk (a family history of psychosis), recent deterioration in functioning, high levels of unusual thought content, high levels of suspicion or paranoia, poor social functioning, and a history of substance abuse (Fusar-Poli et al., 2013). Further research will enable a more accurate prediction of those at greatest risk for developing schizophrenia, and thus to whom early intervention efforts should be directed.

Try It

Figure 3. The most well-known dissociative disorder is dissociative identity disorder, in which people exhibit more than one identity.

Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative disorders are characterized by an individual becoming split off, or dissociated, from her core sense of self. Memory and identity become disturbed; these disturbances have a psychological rather than physical cause. Dissociative disorders listed in the DSM-5 include dissociative amnesia, depersonalization/derealization disorder, and dissociative identity disorder.

Dissociative Amnesia

Amnesia refers to the partial or total forgetting of some experience or event. An individual with dissociative amnesia is unable to recall important personal information, usually following an extremely stressful or traumatic experience such as combat, natural disasters, or being the victim of violence. The memory impairments are not caused by ordinary forgetting. Some individuals with dissociative amnesia will also experience dissociative fugue (from the word “to flee” in French), whereby they suddenly wander away from their home, experience confusion about their identity, and sometimes even adopt a new identity (Cardeña & Gleaves, 2006). Most fugue episodes last only a few hours or days, but some can last longer. One study of residents in communities in upstate New York reported that about 1.8% experienced dissociative amnesia in the previous year (Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, & Brook, 2006).

Some have questioned the validity of dissociative amnesia (Pope, Hudson, Bodkin, & Oliva, 1998); it has even been characterized as a “piece of psychiatric folklore devoid of convincing empirical support” (McNally, 2003, p. 275). Notably, scientific publications regarding dissociative amnesia rose during the 1980s and reached a peak in the mid-1990s, followed by an equally sharp decline by 2003; in fact, only 13 cases of individuals with dissociative amnesia worldwide could be found in the literature that same year (Pope, Barry, Bodkin, & Hudson, 2006). Further, no description of individuals showing dissociative amnesia following a trauma exists in any fictional or nonfictional work prior to 1800 (Pope, Poliakoff, Parker, Boynes, & Hudson, 2006). However, a study of 82 individuals who enrolled for treatment at a psychiatric outpatient hospital found that nearly 10% met the criteria for dissociative amnesia, perhaps suggesting that the condition is underdiagnosed, especially in psychiatric populations (Foote, Smolin, Kaplan, Legatt, & Lipschitz, 2006).

Try It

Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder

Depersonalization/derealization disorder is characterized by recurring episodes of depersonalization, derealization, or both. Depersonalization is defined as feelings of “unreality or detachment from, or unfamiliarity with, one’s whole self or from aspects of the self” (APA, 2013, p. 302). Individuals who experience depersonalization might believe their thoughts and feelings are not their own; they may feel robotic as though they lack control over their movements and speech; they may experience a distorted sense of time and, in extreme cases, they may sense an “out-of-body” experience in which they see themselves from the vantage point of another person. Derealization is conceptualized as a sense of “unreality or detachment from, or unfamiliarity with, the world, be it individuals, inanimate objects, or all surroundings” (APA, 2013, p. 303). A person who experiences derealization might feel as though he is in a fog or a dream, or that the surrounding world is somehow artificial and unreal. Individuals with depersonalization/derealization disorder often have difficulty describing their symptoms and may think they are going crazy (APA, 2013).

Dissociative Identity Disorder

By far, the most well-known dissociative disorder is dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder). People with dissociative identity disorder exhibit two or more separate personalities or identities, each well-defined and distinct from one another. They also experience memory gaps for the time during which another identity is in charge (e.g., one might find unfamiliar items in her shopping bags or among her possessions), and in some cases may report hearing voices, such as a child’s voice or the sound of somebody crying (APA, 2013). The study of upstate New York residents mentioned above (Johnson et al., 2006) reported that 1.5% of their sample experienced symptoms consistent with dissociative identity disorder in the previous year.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is highly controversial. Some believe that people fake symptoms to avoid the consequences of illegal actions (e.g., “I am not responsible for shoplifting because it was my other personality”). In fact, it has been demonstrated that people are generally skilled at adopting the role of a person with different personalities when they believe it might be advantageous to do so. As an example, Kenneth Bianchi was an infamous serial killer who, along with his cousin, murdered over a dozen females around Los Angeles in the late 1970s. Eventually, he and his cousin were apprehended. At Bianchi’s trial, he pled not guilty by reason of insanity, presenting himself as though he had DID and claiming that a different personality (“Steve Walker”) committed the murders. When these claims were scrutinized, he admitted faking the symptoms and was found guilty (Schwartz, 1981).

A second reason DID is controversial is because rates of the disorder suddenly skyrocketed in the 1980s. More cases of DID were identified during the five years prior to 1986 than in the preceding two centuries (Putnam, Guroff, Silberman, Barban, & Post, 1986). Although this increase may be due to the development of more sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is also possible that the popularization of DID—helped in part by Sybil, a popular 1970s book (and later film) about a woman with 16 different personalities—may have prompted clinicians to overdiagnose the disorder (Piper & Merskey, 2004). Casting further scrutiny on the existence of multiple personalities or identities is the recent suggestion that the story of Sybil was largely fabricated, and the idea for the book might have been exaggerated (Nathan, 2011).

Despite its controversial nature, DID is clearly a legitimate and serious disorder, and although some people may fake symptoms, others suffer their entire lives with it. People with this disorder tend to report a history of childhood trauma, some cases having been corroborated through medical or legal records (Cardeña & Gleaves, 2006). Research by Ross et al. (1990) suggests that in one study about 95% of people with DID were physically and/or sexually abused as children. Of course, not all reports of childhood abuse can be expected to be valid or accurate. However, there is strong evidence that traumatic experiences can cause people to experience states of dissociation, suggesting that dissociative states—including the adoption of multiple personalities—may serve as a psychologically important coping mechanism for threat and danger (Dalenberg et al., 2012).

Link to Learning

Review the differences between schizophrenia and the once-called multiple personality disorder in the following episode of CrashCourse Psychology.

Try It

Think It Over

- Try to find an example (via a search engine) of a past instance in which a person committed a horrible crime, was apprehended, and later claimed to have dissociative identity disorder during the trial. What was the outcome? Was the person revealed to be faking? If so, how was this determined?

Glossary