Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) definition of pain highlights the multidimensional components of pain. The interaction of these dimensions (sensory-discriminative: intensity, location, quality and behavior of pain; cognitive-evaluative: thoughts of the pain as influenced by previous experiences and knowledge; and motivational-affective: emotional responses like anger, anxiety and fear that motivate the response to pain)[1] all contribute to the complexity of the painful experience. An individual’s belief systems, pain understanding, thoughts and emotions: anxiety; depression; catastrophizing (or their psychology) influence how the brain interprets a noxious stimulus in relation to the meaning and level of threat the stimulus pose to one’s well-being, and thereby influence the resulting output from the brain[2]. Such resulting changes in behavior (i.e. avoidance)[3][4] such as fear avoidance, catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, stress and learned helplessness can impact upon a pain experience and a patient’s coping strategies. While this is unlikely to be an exclusive list of influential psychosocial factors, the following components are well researched and evidenced. This page will review each of these in turn.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) definition of pain highlights the multidimensional components of pain. The interaction of these dimensions (sensory-discriminative: intensity, location, quality and behavior of pain; cognitive-evaluative: thoughts of the pain as influenced by previous experiences and knowledge; and motivational-affective: emotional responses like anger, anxiety and fear that motivate the response to pain)[1] all contribute to the complexity of the painful experience. An individual’s belief systems, pain understanding, thoughts and emotions: anxiety; depression; catastrophizing (or their psychology) influence how the brain interprets a noxious stimulus in relation to the meaning and level of threat the stimulus pose to one’s well-being, and thereby influence the resulting output from the brain[2]. Such resulting changes in behavior (i.e. avoidance)[3][4] such as fear avoidance, catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, stress and learned helplessness can impact upon a pain experience and a patient’s coping strategies. While this is unlikely to be an exclusive list of influential psychosocial factors, the following components are well researched and evidenced. This page will review each of these in turn.Fear Avoidance

Pain and Fear: Fear is a typical emotional response to an experience that is perceived to be threatening, such as one that leads to a pain sensation[5][6]. Future avoidance of the painful activity is often the resulting behaviour adopted to protect oneself from a repeat of the fearful emotion and painful experience. This pattern can lead to fear and avoidance of work-related activities, movement, and re-injury[7]. Kinesophobia is a term used interchangeably with fear avoidance in health and pain literature. It is defined as “an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or reinjury[8].”

Impact of Fear Avoidance on the Pain Experience

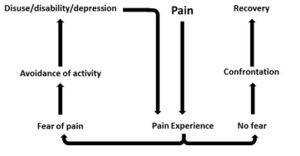

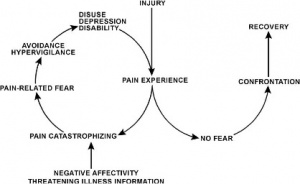

In response to acute tissue damage/injury, feelings of fear are heightened as part of a normal consequence of pain[4]. The individual will rest and protect the painful area as an adaptive behaviour to allow tissue healing to occur[4]. As the acute phase and initial tissue healing resolves, it has been suggested that some individuals can confront their fearful emotions and are able to resume normal activities, which ultimately helps extinguish their fears as they experience positive increase in mobility/movement unassociated with further increases in pain[5]. For others, they may be unable to overcome the fearful emotion and the resulting avoidance behaviour persists[7]. A cycle of continued activity avoidance and fearful emotions may ensue, resulting in chronic pain that may have an adverse effect on the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular system (disuse syndrome)[9], which fundamentally increases disability[4][7][10].

Several models have been proposed to explain the persistence of ‘fear-avoidance’ and its impact on pain and behaviour.

In the fear-avoidance model of pain, individuals who are likely to demonstrate ongoing fear-avoidance behaviours will be inclined to catastrophize[6][7]:

Vlaeyen and Linton[7] have described the interconnections contributing to fear avoidance as follows: with negative appraisals of a painful experience, fear avoidance behaviours are elicited. Due to hypervigilance, the avoidance behaviour begins to occur in anticipation rather than in response to pain. As there are fewer and fewer opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with the avoided activity, the behaviour perpetuates and fear avoidance persists.

While research has consistently shown an association between fear avoidance behavior and pain-related fears[11][12][13][14][15] even when pain intensity and other variables were controlled in patients with chronic pain, there are conflicting studies about this association in patients with acute pain. Studies have shown that high levels of fear avoidance can be a predictor for future episodes of pain[16][17][18][19][20]. But on the contrary, studies[21] showed more support for the link between depression with poor function and disability at this early stage[22][23] In the learning pathway model, fear avoidance becomes a conditioned response through association of pain with movement[7][5][22]. The behavior of avoiding expected pain-provoking movement or activities to prevent new episodes of pain is learned through experience[24]. The individual may anticipate similar experiences and associate non-painful or non-harmful experiences with pain, resulting in persistent fear-avoidance behavior[7][22].

The following factors can affect the strength of association of pain with movement and the fear-avoidance behaviour that patients may exhibit:[25]

- existing beliefs about pain and the meaning of the symptoms

- beliefs about their own ability to control pain (self-efficacy)

- prior learning experiences (either direct experience or observational learning)

- expectations of recovery

- current emotional states (which include catastrophizing, anxiety, depression)

While the above models explain how fear avoidance becomes a maladaptive coping strategy and barrier to recovery in patients with chronic pain, this information may also be relevant to clinicians dealing with patients in the acute stages of injury. Any early fear-avoidance behaviours, especially for those who have strong negative emotions about their pain like anxiety or depression[12][22], could be identified. These patients could be monitored so they do not continue this coping strategy once the acute stage has passed. Knowing what factors affect fear-avoidance would help clinicians elicit these behaviours in their patients, expose any wrongful beliefs, attitudes or coping strategies (active vs passive) patient may have about their pain and recovery, and determine the best way to challenge them.

Physiotherapists managing these patients may find it useful to categorise the type of fear-avoidance patients exhibit. Rainville et al[5] proposed the following categories:

- Misinformed avoiders: have misinformed beliefs about movement and risk of damage or re-injury; may benefit from accurate information about pain and movement (pain physiology)

- Learned avoiders: learned the behaviour without being aware nor overly distressed about it; may benefit from gradual exposure to activity depending on pain tolerance

- Affective avoiders: are distressed and have strong negative cognitions about the pain; may need more cognition-based management and challenge beliefs

While not every patient with chronic pain will fall into any specific model or category, presenting an appropriate model may help the patient to realise the cycle of pain and fear-avoidance behaviour that individual has adopted. Furthermore, explaining how fear avoidance affects the physiological feelings they may be experiencing will help them to understand how their perception of pain may be altered[4][7][6]. For example:

- Increased physiological arousal/heightened muscle reactivity

- Associated anxiety and hyper-vigilance leads to increased attention to expected painful stimulus which in itself can intensify the pain

- Reduced participation in valued activities like work, leisure and social contacts can lead to mood changes like irritability, frustration and depression; these mood changes could further affect perception of pain

- Disuse or disability from persistent avoidance behavior will lead to pain with much less provocation than before (lower the threshold for experiencing future pain).

Several self-reported measures of fear avoidance could be used in the clinic to help assess fear avoidance. These include the following:

- Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) identifies how beliefs about work and physical activity affect low back pain[26]

- Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA) assesses patients attitudes towards pain control, pain-related disability, medical cures of pain, solicitude of others, and medication for pain[27]

- Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) assesses fear of re-injury due to movement[8]

Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety

- Anxiety is a general term for several disorders that include uneasiness, apprehension, nervousness, fear and worrying.

- There is high prevalence of anxiety reported throughout the literature in patients with chronic pain syndromes of varying nature including the following: non-specified/widespread chronic pain[28][29][30][31][32][33], low back pain[34], traumatic musculoskeletal injury (TMsI)[35][36], rotator cuff tear [37]; and also in non-musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions such as phantom limb pain [38], prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome[39] and diabetic neuropathy[40].

- The prevalence of patients in each study purely with anxiety varied throughout, from 18 to 72% of those recruited. Unfortunately much of this literature does not solely focus on anxiety alone.

- The following have been commonly reported anxiety symptoms reported in patients with chronic pain: “not being able to stop worrying,” “worrying about too many different things” and “feeling as though something awful might happen.”

- A study conducted by Asmundson and Taylor in 1996 suggested the relation between anxiety sensitivity and developing pain-related fear and escape/avoidance in people with chronic pain[41].

A study[32] which aimed to evaluate the prediction of chronic pain looked at anxiety, depression and social stressors as risk factors and the severity of pain at 3, 6 and 12 months in 250 patients. They found a strong correlation between baseline anxiety which predicted pain severity at 12 months. Interestingly no correlation was found for social stressors or depression. In a TMsI study, anxiety was found to predict pain intensity at different time-frames post injury whereas depression, social support, length of hospital stay and self-efficacy had no substantial effect. They summarized that pain predicted anxiety and depression in the first year, but anxiety only predicted pain intensity from 12-24 months. Anxiety symptoms were therefore hypothesized as the primary causative factor of persistent pain in this cohort study. It is therefore important to address patients anxiety early to prevent it persisting and causing a negative barrier to their recovery.

One study examined the validity of a single question to screen for depression and anxiety[42].

- Single question screening tools were compared with validated questionnaires such as mini-international neuropsychiatric interview, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Hopkins symptom checklist.

- It was found that the single questions demonstrated fair ability to detecting anxiety with a sensitivity of 68% and a good ability to exclude anxiety with a specificity of 85%.

- Therefore, single question screening tools are fairly effective in identifying anxiety and could be utilised into early assessments with chronic pain patients.

Depression

Depression is described as a general term for mental disorders which include: sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of low self-worth and low mood.

- Some frequently reported depressive symptoms among chronic pain patients are: “thinking of suicide/self harm” and “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”.

- Depression alone is associated with: chronic MSK[43] and widespread pain, knee pain[44], low back pain and chronic pelvic pain/prostatitis[45].

- In a study examining the impact of anxiety and depression in phantom limb pain (PLP) patients, mean depression scores were higher, although non-significant, in patients with non-PLP chronic pain syndromes[46].

A study of low back pain observed higher prevalence of depression symptoms (13.7%) compared to anxiety symptoms (9.5%)[47].

- Similarly, a cohort of 400 patients with chronic myofascial or neuropathic pain demonstrated higher prevalence of depression (93%) than anxiety (72%)[48].

Pain, Anxiety and Depression Anxiety and depression appear to be overlapping conditions. Much of the literature has acknowledged their joint effect in chronic pain patients[49].

A study in Brazil, which included 400 chronic pain patients, observed 54% with both of the psychiatric disorders compared to anxiety (18%) or depression (7%) alone[50]. In patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, those with both anxiety and depression experienced the greatest pain severity, a highly significant finding. Furthermore combined psychiatric co-morbidity was strongly associated with disability days with the following: 18.1 days in pain-only patients, 32.2 in those with pain and anxiety, 38.0 days in those with pain and depression and 42.6 days in those with all three conditions. This study also found a significant correlation with reduced QoL when all three conditions presented together[33].

Thus it comes into question as to why these psychiatric disorders:

a) present together,

b) develop with the onset of traumatic pain,

c) appear to cause acute pain to persist; and

d) cause more severe functional deficit together than when presenting independently.

Many studies have looked into the pathophysiology of pain, anxiety and depression to find answers and to facilitate more successful treatment of these complex conditions[51][52][53].

Impact of Depression and Anxiety on the Pain Experience

Anxiety

A physiological model of anxiety may explain its role in pain perception;

- It is known that a state of acute anxiety stimulates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), causing increased muscle tension, increased nociceptive input and increased sensitivity to pain stimuli, thus explaining why anxiety may correspond to increased pain perception.

- Corticosteroid hormones, for example, released after stress may play a part in pain modulation[54], as cortisol (a steroid hormone known to stimulate the SNS) has been found in higher levels in those with chronic pain[55].

- Furthermore neurotransmitters, neuropeptides and pro-inflammatory cytokines have been found to either mediate or modulate pain. Therefore, these physiological processes overlap in both anxiety and pain.

- There is evidence accumulating to show atypical sensory processing in the brain and dysfunction of skeletal muscle nociception[54][56], however the latter may not explain pain persistence in non-MSK pathologies where chronic pain has clearly been observed.

- The “pain matrix”[57], responsible for modulation of pain signals in the central nervous system (CNS), shares elements with brain networks responsible for stress, identifying another connection to the SNS. Pain contributes to feelings of anxiety due to fear of the cause, and if this persists a state of hypervigilance and avoidance behaviors may develop as a “maladaptive” coping response.

- A more permanent state of anxiety results in chronic muscle tension and anticipatory anxiety which leads to further disability.

- Decreases in activities, especially those which provide meaning and reinforcement, may result in greater social isolation, decreased self-efficacy, increased feelings of uselessness and subsequent increases in anxiety and depression symptoms.

This theory is closely interlinked with the ‘fear-avoidance’ model, a cycle prospected to play a vital part in sustenance of pain behaviors and which has been shown to be an independent predictor of pain severity and disability among those with MSK pain[58].

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies along with blood-oxygenated level dependent contrast (BOLD) techniques have been utilized in various studies to map common areas of brain activation by detecting changes in blood flow. These studies have been able to map similar areas of brain activation for anxiety and pain. It has been shown that there is exaggerated brain response in patients with social anxiety disorder[59].

- In one study these methods were used to identify highlighted areas in the brain when anxious patients reacted to negative self-beliefs.

- The areas identified were the midline cortical regions such as: the ventromedial pre-frontal cortex (PFC), dorsomedial PFC, posterior cingulate cortex (implicated in self-referential process), emotional center (amygdala) and memory area (hippocampal gyrus)[59].

- This indicates that there are integrated neural pathways associated with anxiety, pain processing, memory and concept of the self – the latter potentially implicating personality traits into anxiety and pain.

Depression

There is less known evidence about the physiology of depression compared to anxiety, however it has been postulated that people with depression or a depressive personality have a greater sensitivity to acute and chronic pain[33].

- Similarly to anxiety, excessive sympathetic activity and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine production is also postulated in the etiology of depression, thus providing a potential physiological link between all three conditions and a possible reason for the overlapping prevalence within patient presentations.

- fMRI studies have been conducted in patients with depressive disorders and similar findings have been identified as in anxious patients.

- In diabetic patients with depression, similar brain activation was identified in both neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain patients; these were PFC, thalamus, insula and anterior cingulate cortex.

- Despite these CNS observations, it is known that in healthy, non-depressed human volunteers, pain-intensity related hemodynamic changes have been observed in all of the above brain sites[60]. Further studies compared the response of brain areas with BOLD techniques:

- 13 patients suffering from an acute episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) were investigated during painful stimulus application and compared to 13 control subjects[61].

- The results demonstrated increased activation of the pain matrix and increased thermal pain thresholds compared to healthy subjects.

- They speculated that the brain area activation may be linked to an underlying prefrontal psychopathology in depression.

In another BOLD study[62] patients with diagnosed MDD showed greater activation of pain-related brain sites (right insular, dorsal anterior cingulate, right amygdala) during anticipation of painful, heat stimuli compared with healthy subjects.

- Furthermore, in MDD subjects, greater activation of the amygdala was associated with greater levels of perceived helplessness.

- This implies anticipation of pain may further pain experience and activation of the pain matrix potentially contributing to persistence of pain.

In other studies, the cingulate and PFC have also been implicated in pain modulation and may contribute to chronic pain associated with fibromyalgia syndrome[54]. The brain is perceived as a mediator for nociceptive pain, but also for pain behaviors which are known to influence pain itself, likely causing its persistence. ‘Central sensitization syndrome’ (CSS) is a highly recognized symptom of chronic pain syndrome. Hyperesthesia and allodynia (increased sensitivity to painful and non-painful stimuli) are features of CSS and have been suggested to be mediated by synaptic strengthening and neuroplastic change at multiple CNS levels, further strengthening the hypothesis of the brain’s role in nociceptive changes in the periphery[63].

- Other researchers have proposed that anxiety and depression may have similar physiological effects on programming in the brain providing more evidence for the relationship[33]. It is clear from research studies that physiology of depression, anxiety and pain are overlapping. However, it is difficult to differentiate the primary versus secondary cause.

Catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing refers to a negative cognitive-affective response to anticipated or actual pain[64]. It was formally introduced by Albert Ellis and was used to describe a maladaptive cognitive style in those with anxiety and depressive disorders[65]. The research focused on the fact that catastrophizing was an exaggerated and negative cognitive and emotional response during an actual or anticipated painful stimulation. Catastrophizing is often characterized by people magnifying their feelings about painful situations and ruminating about them, which can combine with feelings of helplessness[66]. Catastrophizing plays an important role in models of pain chronicity, showing a high correlation with both pain intensity and disability[67]. However, it is also apparent that fear-avoidance and depression are important predictors of pain intensity and disability[68]. High correlations between fear-avoidance and pain catastrophizing have been found[69]. In studies, however, only pain catastrophizing predicted pain intensity[70]. Additionally, catastrophizing has also been linked to adverse pain outcomes[71][72][73]. It can therefore be surmised that a reduction in pain catastrophizing will lead to a reduction in pain and disability[74]. This highlights the importance of a multifactorial approach to pain management and the significance catastrophizing has in molding the pain experience.

How Can We Assess the Levels of Catastrophizing?

Research has developed self-report instruments that can be used in various populations[75]. Most commonly used is a 3-factor hierarchical structure for pain catastrophizing called The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). This scale incorporates magnification, rumination and helplessness. Highlighting the need for a multifactorial approach, participants are asked to rate the extent to which they experience each item by recalling previous experiences with pain[76]. More negative experiences with pain can correlate with higher levels of pain intensity and disability[77].

Why does this happen?

There are various theoretical mechanisms of action including the appraisal theory[78], where the levels of helplessness the person is feeling will affect their ability to cope. Additional mechanisms include attention bias/information processing[79], where the catastrophizing amplifies the experience of pain via amplified attention biases to sensory and affective pain information[80], and an inability to suppress pain-related cognitions[81]. Evidence has also suggested that there is an increased nociceptive transmission via spinal gating mechanisms and a central sensitization of pain. This may represent a central nervous mechanism which is contributing to the development, maintenance and aggravation of persistent pain[82][83][84].

It is therefore apparent that both psychological and physiological factors play a major role in the perception, maintenance, experience and management of pain; and both directly influence each other. It is important to recognize these factors in both the acute and chronic pain patient in order to understand what aspects of their pain are a barrier to recovery.

As discussed previously, psycho-social factors including depression, anxiety or fear-avoidance all factor into the pain experience and have distinct acute and chronic effects on the brain. Additionally, chronic stress contributes to pain sensitization via physiological changes occurring during the sympathetic response[85]. These changes are mediated primarily by cortisol, an anti-inflammatory neuroendocrine hormone. In the short term, the stress response is a physiologic flight-or-fight response, in which secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine (sympathetic neurotransmitters) and cortisol promote survival. The immediate pro-inflammatory stage of the stress response, governed by the sympathetic neurotransmitters, is marked by increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration, as well as vasoconstriction and pupillary dilation. The latter stage of the stress response occurs as a delayed, systematic increase in cortisol levels 15 minutes after the initial stress response. The anti-inflammatory activity of cortisol acts to suppress non-vital organs, mobilize glucose reserves, and lower inflammation[85].

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Cortisol Dysfunction

Cortisol Dysfunction: Effects on Pain

Cortisol dysfunction has been implicated in various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, ranging from osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic fatigue syndrome, among others[85]. HPA axis exhaustion and cortisol dysfunction can manifest as stress-induced hypocortisolism and are associated with musculoskeletal pain conditions including chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia. Additional studies have suggested hypocortisolism as a predictive risk factor for musculoskeletal pain[87].

Therefore, it is critical to address both pain and non-pain-related stress in treating pain. Such measures may include objective cortisol readings in a medical setting, or subjective self-reports of stress as part of a screening or physiotherapy evaluation. By identifying stress factors or maladaptive coping strategies early in the screening process, providers can educate patients about chronic pain and the interplay between psychosocial factors and pain. Physiotherapists may also utilize pain neuroscience education. Stress management, psychological approaches to pain management and pain education can ultimately empower patients in their recovery as part of a multi-factorial pain rehabilitation program[85].