The Transtheoretical Model (Stages of Change)

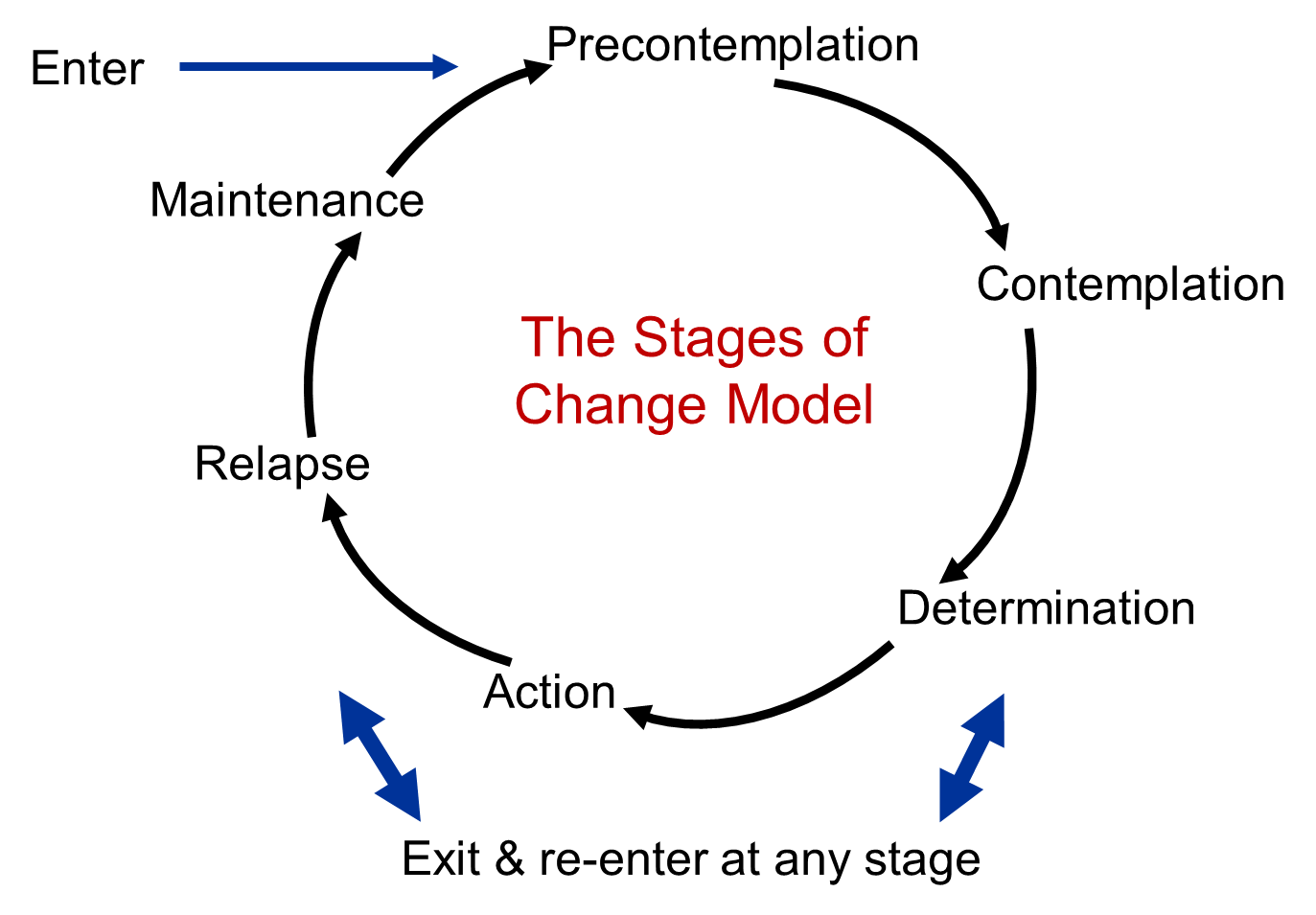

The Transtheoretical Model (also called the Stages of Change Model), developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in the late 1970s, evolved through studies examining the experiences of smokers who quit on their own with those requiring further treatment to understand why some people were capable of quitting on their own. It was determined that people quit smoking if they were ready to do so. Thus, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) focuses on the decision-making of the individual and is a model of intentional change. The TTM operates on the assumption that people do not change behaviors quickly and decisively. Rather, change in behavior, especially habitual behavior, occurs continuously through a cyclical process. The TTM is not a theory but a model; different behavioral theories and constructs can be applied to various stages of the model where they may be most effective.

The TTM posits that individuals move through six stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination. Termination was not part of the original model and is less often used in application of stages of change for health-related behaviors. For each stage of change, different intervention strategies are most effective at moving the person to the next stage of change and subsequently through the model to maintenance, the ideal stage of behavior.

- Precontemplation – In this stage, people do not intend to take action in the foreseeable future (defined as within the next 6 months). People are often unaware that their behavior is problematic or produces negative consequences. People in this stage often underestimate the pros of changing behavior and place too much emphasis on the cons of changing behavior.

- Contemplation – In this stage, people are intending to start the healthy behavior in the foreseeable future (defined as within the next 6 months). People recognize that their behavior may be problematic, and a more thoughtful and practical consideration of the pros and cons of changing the behavior takes place, with equal emphasis placed on both. Even with this recognition, people may still feel ambivalent toward changing their behavior.

- Preparation (Determination) – In this stage, people are ready to take action within the next 30 days. People start to take small steps toward the behavior change, and they believe changing their behavior can lead to a healthier life.

- Action – In this stage, people have recently changed their behavior (defined as within the last 6 months) and intend to keep moving forward with that behavior change. People may exhibit this by modifying their problem behavior or acquiring new healthy behaviors.

- Maintenance – In this stage, people have sustained their behavior change for a while (defined as more than 6 months) and intend to maintain the behavior change going forward. People in this stage work to prevent relapse to earlier stages.

- Termination – In this stage, people have no desire to return to their unhealthy behaviors and are sure they will not relapse. Since this is rarely reached, and people tend to stay in the maintenance stage, this stage is often not considered in health promotion programs.

To progress through the stages of change, people apply cognitive, affective, and evaluative processes. Ten processes of change have been identified with some processes being more relevant to a specific stage of change than other processes. These processes result in strategies that help people make and maintain change.

- Consciousness Raising – Increasing awareness about the healthy behavior.

- Dramatic Relief – Emotional arousal about the health behavior, whether positive or negative arousal.

- Self-Reevaluation – Self reappraisal to realize the healthy behavior is part of who they want to be.

- Environmental Reevaluation – Social reappraisal to realize how their unhealthy behavior affects others.

- Social Liberation – Environmental opportunities that exist to show society is supportive of the healthy behavior.

- Self-Liberation – Commitment to change behavior based on the belief that achievement of the healthy behavior is possible.

- Helping Relationships – Finding supportive relationships that encourage the desired change.

- Counter-Conditioning – Substituting healthy behaviors and thoughts for unhealthy behaviors and thoughts.

- Reinforcement Management – Rewarding the positive behavior and reducing the rewards that come from negative behavior.

- Stimulus Control – Re-engineering the environment to have reminders and cues that support and encourage the healthy behavior and remove those that encourage the unhealthy behavior.

Limitations of the Transtheoretical Model

There are several limitations of TTM, which should be considered when using this theory in public health. Limitations of the model include the following:

- The theory ignores the social context in which change occurs, such as SES and income.

- The lines between the stages can be arbitrary with no set criteria of how to determine a person’s stage of change. The questionnaires that have been developed to assign a person to a stage of change are not always standardized or validated.

- There is no clear sense for how much time is needed for each stage, or how long a person can remain in a stage.

- The model assumes that individuals make coherent and logical plans in their decision-making process when this is not always true.

The Transtheoretical Model provides suggested strategies for public health interventions to address people at various stages of the decision-making process. This can result in interventions that are tailored (i.e., a message or program component has been specifically created for a target population’s level of knowledge and motivation) and effective. The TTM encourages an assessment of an individual’s current stage of change and accounts for relapse in people’s decision-making process.

watch

SMART Goal Setting

Have you ever said to yourself that you need to “eat healthier” or “exercise more” to improve your overall health? How well did that work for you? In most cases, probably not very well. That’s because these statements are too vague and do not give us any direction for what truly needs to be done to achieve such goals. To have a better chance at being successful, try using the SMART acronym for setting your goals (S= Specific, M= Measurable, A=Attainable, R= Realistic, T= Time-oriented):

Specific – Create a goal that has a focused and clear path for what you actually need to do. Examples:

- I will drink 8 ounces of water 3 times per day

- I will walk briskly for 30 minutes, 5 times per week

- I will reduce my soda intake to no more than 2 cans of soda per week

Do you see how that is more helpful than just saying you will eat healthier or exercise more? It gives you direction.

Measurable – This enables you to track your progress, and ties in with the “specific” component. The above examples all have actual numbers associated with the behavior change that let you know whether or not it has been met.

Attainable – Make sure that your goal is within your capabilities and not too far out of reach. For example, if you have not been physically active for a number of years, it would be highly unlikely that you would be able to achieve a goal of running a marathon within the next month.

Realistic – Try to ensure that your goal is something you will be able to continue doing and incorporate as part of your regular routine/lifestyle. For example, if you made a goal to kayak 2 times each week, but don’t have the financial resources to purchase or rent the equipment, no way to transport it, or are not close enough to a body of water in which to partake in kayaking, then this is not going to be feasible.

Time-oriented – Give yourself a target date or deadline in which the goal needs to be met. This will keep you on track and motivated to reach the goal, while also evaluating your progress.

Changing Your Habits for Better Health

Are you thinking about being more active? Have you been trying to cut back on less healthy foods? Are you starting to eat better and move more but having a hard time sticking with these changes?

Old habits die hard. Changing your habits is a process that involves several stages. Sometimes it takes a while before changes become new habits. And, you may face roadblocks along the way.

Adopting new, healthier habits may protect you from serious health problems like obesity and diabetes. New habits, like healthy eating and regular physical activity, may also help you manage your weight and have more energy. After a while, if you stick with these changes, they may become part of your daily routine.

The information below outlines four stages you may go through when changing your health habits or behavior. You will also find tips to help you improve your eating, physical activity habits, and overall health. The four stages of changing a health behavior are

- contemplation

- preparation

- action

- maintenance

What stage of change are you in?

Contemplation: “I’m thinking about it.”

In this first stage, you are thinking about change and becoming motivated to get started.

You might be in this stage if you

- have been considering change but are not quite ready to start

- believe that your health, energy level, or overall well-being will improve if you develop new habits

- are not sure how you will overcome the roadblocks that may keep you from starting to change

Preparation: “I have made up my mind to take action.”

In this next stage, you are making plans and thinking of specific ideas that will work for you.

You might be in this stage if you

- have decided that you are going to change and are ready to take action

- have set some specific goals that you would like to meet

- are getting ready to put your plan into action

Action: “I have started to make changes.”

In this third stage, you are acting on your plan and making the changes you set out to achieve.

You might be in this stage if you

- have been making eating, physical activity, and other behavior changes in the last 6 months or so

- are adjusting to how it feels to eat healthier, be more active, and make other changes such as getting more sleep or reducing screen time

- have been trying to overcome things that sometimes block your success

Maintenance: “I have a new routine.”

In this final stage, you have become used to your changes and have kept them up for more than 6 months.

You might be in this stage if

- your changes have become a normal part of your routine

- you have found creative ways to stick with your routine

- you have had slip-ups and setbacks but have been able to get past them and make progress

Did you find your stage of change? Read on for ideas about what you can do next.

Contemplation: Are you thinking of making changes?

Making the leap from thinking about change to taking action can be hard and may take time. Asking yourself about the pros (benefits) and cons (things that get in the way) of changing your habits may be helpful. How would life be better if you made some changes?

Think about how the benefits of healthy eating or regular physical activity might relate to your overall health. For example, suppose your blood glucose, also called blood sugar, is a bit high and you have a parent, brother, or sister who has type 2 diabetes. This means you also may develop type 2 diabetes. You may find that it is easier to be physically active and eat healthy knowing that it may help control blood glucose and protect you from a serious disease.

You may learn more about the benefits of changing your eating and physical activity habits from a health care professional. This knowledge may help you take action.

Look at the lists of pros and cons below. Find the items you believe are true for you. Think about factors that are important to you.

Healthy Eating

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Physical Activity

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Preparation: Have you made up your mind?

If you are in the preparation stage, you are about to take action. To get started, look at your list of pros and cons. How can you make a plan and act on it?

The chart below lists common roadblocks you may face and possible solutions to overcome roadblocks as you begin to change your habits. Think about these things as you make your plan.

| Roadblock | Solution |

|---|---|

| I don’t have time. | Make your new healthy habit a priority. Fit in physical activity whenever and wherever you can. Try taking the stairs or getting off the bus a stop early if it is safe to do so. Set aside one grocery shopping day a week, and make healthy meals that you can freeze and eat later when you don’t have time to cook. |

| Healthy habits cost too much. | You can walk around the mall, a school track, or a local park for free. Eat healthy on a budget by buying in bulk and when items are on sale, and by choosing frozen or canned fruits and vegetables. |

| I can’t make this change alone. | Recruit others to be active with you, which will help you stay motivated and safe. Consider signing up for a fun fitness class like salsa dancing. Get your family or coworkers on the healthy eating bandwagon. Plan healthy meals together with your family, or start a healthy potluck once a week at work. |

| I don’t like physical activity. | Forget the old notion that being physically active means lifting weights in a gym. You can be active in many ways, including dancing, walking, or gardening. Make your own list of options that appeal to you. Explore options you never thought about, and stick with what you enjoy. |

| I don’t like healthy foods. | Try making your old favorite recipes in healthier new ways. For example, you can trim fat from meats and reduce the amount of butter, sugar, and salt you cook with. Use low-fat cheeses or milk rather than whole-milk foods. Add a cup or two of broccoli, carrots, or spinach to casseroles or pasta. |

Once you have made up your mind to change your habits, make a plan and set goals for taking action. Here are some ideas for making your plan:

- learn more about healthy eating External link and food portions

- learn more about being physically active

- make lists of

- healthy foods that you like or may need to eat more of—or more often

- foods you love that you may need to eat less often

- things you could do to be more physically active

- fun activities you like and could do more often, such as dancing

After making your plan, start setting goals for putting your plan into action. Start with small changes. For example, “I’m going to walk for 10 minutes, three times a week.” What is the one step you can take right away?

Action: Have you started to make changes?

You are making real changes to your lifestyle, which is fantastic! To stick with your new habits

- review your plan

- look at the goals you set and how well you are meeting them

- overcome roadblocks by planning ahead for setbacks

- reward yourself for your hard work

Track your progress

- Tracking your progress helps you spot your strengths, find areas where you can improve, and stay on course. Record not only what you did, but how you felt while doing it—your feelings can play a role in making your new habits stick.

- Recording your progress may help you stay focused and catch setbacks in meeting your goals. Remember that a setback does not mean you have failed. All of us experience setbacks. The key is to get back on track as soon as you can.

- You can track your progress with online tools such as the NIH Body Weight Planner. The NIH Body Weight Planner lets you tailor your calorie and physical activity plans to reach your personal goals within a specific time period.

Overcome roadblocks

- Remind yourself why you want to be healthier. Perhaps you want the energy to play with your nieces and nephews or to be able to carry your own grocery bags. Recall your reasons for making changes when slip-ups occur. Decide to take the first step to get back on track.

- Problem-solve to “outsmart” roadblocks. For example, plan to walk indoors, such as at a mall, on days when bad weather keeps you from walking outside.

- Ask a friend or family member for help when you need it, and always try to plan ahead. For example, if you know that you will not have time to be physically active after work, go walking with a coworker at lunch or start your day with an exercise video.

Reward yourself

- After reaching a goal or milestone, allow for a nonfood reward such as new workout gear or a new workout device. Also consider posting a message on social media to share your success with friends and family.

- Choose rewards carefully. Although you should be proud of your progress, keep in mind that a high-calorie treat or a day off from your activity routine are not the best rewards to keep you healthy.

- Pat yourself on the back. When negative thoughts creep in, remind yourself how much good you are doing for your health by moving more and eating healthier.

Maintenance: Have you created a new routine?

Make your future a healthy one. Remember that eating healthy, getting regular physical activity, and other healthy habits are lifelong behaviors, not one-time events. Always keep an eye on your efforts and seek ways to deal with the planned and unplanned changes in life.

Now that healthy eating and regular physical activity are part of your routine, keep things interesting, avoid slip-ups, and find ways to cope with what life throws at you.

Add variety and stay motivated

- Mix up your routine with new physical activities and goals, physical activity buddies, foods, recipes, and rewards.

Deal with unexpected setbacks

- Plan ahead to avoid setbacks. For example, find other ways to be active in case of bad weather, injury, or other issues that arise. Think of ways to eat healthy when traveling or dining out, like packing healthy snacks while on the road or sharing an entrée with a friend in a restaurant.

- If you do have a setback, don’t give up. Setbacks happen to everyone. Regroup and focus on meeting your goals again as soon as you can.

Challenge yourself!

- Revisit your goals and think of ways to expand them. For example, if you are comfortable walking 5 days a week, consider adding strength training twice a week. If you have limited your saturated fat intake by eating less fried foods, try cutting back on added sugars, too. Small changes can lead to healthy habits worth keeping.