Most college writing has some basic features in common: a sense of ethical responsibility and the use of credible and credited sources, critical thinking, and sound argumentation. In addition to these common features, each academic discipline, over many generations, has developed its own specific methods of asking questions and sharing answers. This chapter will show you how to use the lenses of various academic disciplines to develop your writing, reading, and thinking.

3.1 Exploring Academic Disciplines

Learning Objectives

- Survey the landscape of academic disciplines.

- Appreciate how academic disciplines help shape how we understand the world.

- Understand that academic disciplines are constantly in flux, negotiating the terms, conditions, and standards of inquiry, attribution, and evidence.

The following table shows one version of the main academic disciplines and some of their branches.

| Discipline | Branch Examples |

|---|---|

| Business | Accounting, economics, finance, management, marketing |

| Humanities | Art, history, languages, literature, music, philosophy, religion, theater |

| Natural and applied sciences | Biology, chemistry, computer science, engineering, geology, mathematics, physics, medicine |

| Social sciences | Anthropology, education, geography, law, political science, psychology, sociology |

Since the makeup of the different branches is always in flux and since the history of any institution of higher education is complicated, you will likely find some overlapping and varying arrangements of disciplines at your college.

Part of your transition into higher education involves being aware that each discipline is a distinct discourse community with specific vocabularies, styles, and modes of communication. Later in your college career, you will begin your writing apprenticeship in a specific discipline by studying the formats of published articles within it. You will look for the following formal aspects of articles within that discipline and plan to emulate them in your work:

- Title format

- Introduction

- Overall organization

- Tone (especially level of formality)

- Person (first, second, or third person)

- Voice (active or passive)

- Sections and subheads

- Use of images (photos, tables, graphics, graphs, etc.)

- Discipline-specific vocabulary

- Types of sources cited

- Use of source information

- Conclusion

- Documentation style (American Psychological Association, Modern Language Association, Chicago, Council of Science Editors, and so on; for more on this, see Chapter 22 “Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation”)

- Intended audience

- Published format (print or online)

Different disciplines tend to recommend collecting different types of evidence from research sources. For example, biologists are typically required to do laboratory research; art historians often use details from a mix of primary and secondary sources (works of art and art criticism, respectively); social scientists are likely to gather data from a variety of research study reports and direct ethnographic observation, interviews, and fieldwork; and a political scientist uses demographic data from government surveys and opinion polls along with direct quotations from political candidates and party platforms.

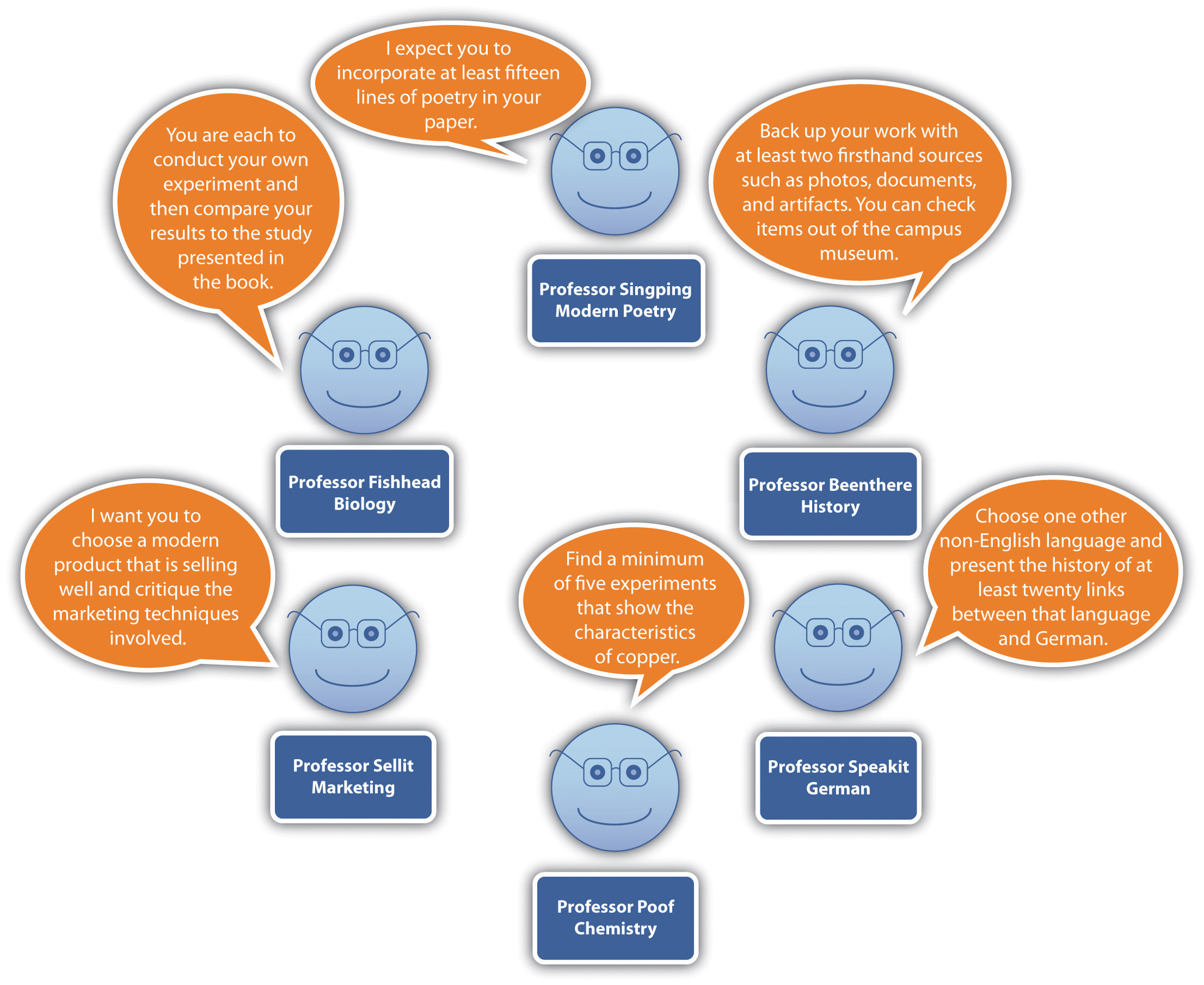

Consider the following circle of professors. They are all asking their students to conduct research in a variety of ways using a variety of sources.

What’s required to complete a basic, introductory essay might essentially be the same across all disciplines, but some types of assignments require discipline-specific organizational features. For example, in business disciplines, documents such as résumés, memos, and product descriptions require a specialized organization. Science and engineering students follow specific conventions as they write lab reports and keep notebooks that include their drawings and results of their experiments. Students in the social sciences and the humanities often use specialized formatting to develop research papers, literature reviews, and book reviews.

Part of your apprenticeship will involve understanding the conventions of a discipline’s key genres. If you are reading or writing texts in the social sciences, for example, you will notice a meticulous emphasis on the specifics of methodology (especially key concepts surrounding the collection of data, such as reliability, validity, sample size, and variables) and a careful presentation of results and their significance. Laboratory reports in the natural and applied sciences emphasize a careful statement of the hypothesis and prediction of the experiment. They also take special care to account for the role of the observer and the nature of the measurements used in the investigation to ensure that it is replicable. An essay in the humanities on a piece of literature might spend more time setting a theoretical foundation for its interpretation, it might also more readily draw from a variety of other disciplines, and it might present its “findings” more as questions than as answers. As you are taking a variety of introductory college courses, try to familiarize yourself with the jargon of each discipline you encounter, paying attention to its specialized vocabulary and terminology. It might even help you make a list of terms in your notes.

Scholars also tend to ask discipline-related kinds of questions. For example, the question of “renewable energy” might be a research topic within different disciplines. The following list shows the types of questions that would accommodate the different disciplines:

- Business (economics): Which renewable resources offer economically feasible solutions to energy issues?

- Humanities (history): At what point did humans switch from the use of renewable resources to nonrenewable resources?

- Natural and applied sciences (engineering): How can algae be developed at a pace and in the quantities needed to be a viable main renewable resource?

- Social sciences (geography): Which US states are best suited to being key providers of renewable natural resources?

Key Takeaways

- Most academic disciplines have developed over many generations. Even though these disciplines are constantly in flux, they observe certain standards for investigation, proof, and documentation of evidence.

- To meet the demands of writing and thinking in a certain discipline, you need to learn its conventions.

- An important aspect of being successful in college (and life) involves being aware of what academic disciplines (and professions and occupations) have in common and how they differ.

Exercises

-

Think about your entire course load this semester as a collection of disciplines. For each course you are taking, answer the following questions, checking your textbooks and other course materials and consulting with your instructors, if necessary:

- What kinds of questions does this discipline ask?

- What kinds of controversies exist in this discipline?

- How does this discipline share the knowledge it constructs?

- How do writers in this discipline demonstrate their credibility?

After you’ve asked and answered these questions about each discipline in isolation, consider what underlying things your courses have in common, even if they approach the world very differently on the surface.

-

Based on the example at the end of this section, pick a topic that multiple disciplines study. Formulate four questions about the topic, one from each of any four different disciplines. Ideally choose a topic that might come up in four courses you are currently taking or have recently taken, or choose a topic of particular interest to you. Here are just a few examples to get you started:

- Alcoholism

- Child abuse

- Poverty in developing nations

- Fast food

- Women in the workforce

- Drawing from the synopses of current research on the Arts and Letters Daily website (see the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader”), read the article referenced on a topic or theme of interest to you. Discuss how the author’s discipline affects the way the topic or theme is presented (specifically, the standards of inquiry and evidence).

3.2 Seeing and Making Connections across Disciplines

Learning Objectives

- Learn how to look for connections between the courses you are taking in different disciplines.

- Witness how topics and issues are connected across disciplines, even when they are expressed differently.

- Understand how to use disciplines to apply past knowledge to new situations.

Section 3.1 “Exploring Academic Disciplines” focused on the formal differences among various academic disciplines and their discourse communities. This section will explore the intellectual processes and concepts disciplines share in common. Even though you will eventually enter a discipline as an academic specialization (major) and as a career path (profession), the first couple of years of college may well be the best opportunity you will ever have to discover how disciplines are connected.

That process may be a rediscovery, given that in the early grades (K–5), you were probably educated by one primary teacher each year covering a set of subjects in a single room. Even though you likely covered each subject in turn, that elementary school classroom was much more conducive to making connections across disciplines than your middle school or high school environment. If you’ve been educated in public schools during the recent era of rigid standardization and multiple-choice testing conducted in the name of “accountability,” the disciplines may seem more separate from one another in your mind than they actually are. In some ways, the first two years of your college experience are a chance to recapture the connections across disciplines you probably made naturally in preschool and the elementary grades, if only at a basic level at the time.

In truth, all disciplines are strikingly similar. Together, they are the primary reason for the survival and evolution of our species. As humans, we have designed disciplines, over time, to help us understand our world better. New knowledge about the world is typically produced when a practitioner builds on a previous body of work in the discipline, most often by advancing it only slightly but significantly. We use academic and professional disciplines to conduct persistent, often unresolved conversations with one another.

Most colleges insist on a “core curriculum” to make sure you have the chance to be exposed to each major discipline at least once before you specialize and concentrate on one in particular. The signature “Aha!” moments of your intellectual journey in college will come every time you grasp a concept or a process in one course that reminds you of something you learned in another course entirely. Ironically the more of those “Aha!” moments you have in the first two years of college, the better you’ll be at your specialization because you’ll have that much more perspective about how the world around you fits together.

How can you learn to make those “Aha!” moments happen on purpose? In each course you take, instead of focusing merely on memorizing content for the purposes of passing an exam or writing an essay that regurgitates your professor’s lecture notes, learn to look for the key questions and controversies that animate the discipline and energize the professions in it. If you organize your understanding of a discipline around such questions and controversies, the details will make more sense to you, and you will find them easier to master.

Key Takeaways

- Disciplines build on themselves, applying past knowledge to new situations and phenomena in a constant effort to improve understanding of the specific field of study.

- Different disciplines often look at the same facts in different ways, leading to wholly different discoveries and insights.

- Disciplines derive their energy from persistent and open debate about the key questions and controversies that animate them.

Exercises

- Arrange at least one interview with at least one of your instructors, a graduate student, or a working professional in a discipline in which you are interested in studying or pursuing as a career. Ask your interviewee(s) to list and describe three of the most persistent controversies, questions, and debates in the field. After absorbing the response(s), write up a report in your own words about the discipline’s great questions.

- Using a textbook or materials from another course you are taking, describe a contemporary controversy surrounding the ways a discipline asks questions or shares evidence and a historical controversy that appears to have been resolved.

- Using one of your library’s disciplinary databases or the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader”, find a document that is at least fifty years old operating in a certain discipline, perhaps a branch of science, history, international diplomacy, political science, law, or medicine. The Smithsonian Institution or Avalon Project websites are excellent places to start your search. Knowing what you know about the current conventions and characteristics of the discipline through which this document was produced, how does its use of the discipline differ from the present day? How did the standards of the discipline change in the interim to make the document you’ve found seem so different? Have those standards improved or declined, in your opinion?

3.3 Articulating Multiple Sides of an Issue

Learning Objectives

- Explore how to recognize binary oppositions in various disciplines.

- Learn the value of entertaining two contradictory but plausible positions as part of your thinking, reading, and writing processes.

- Appreciate the productive, constructive benefits of using disciplinary lenses and borrowing from other disciplines.

Regardless of the discipline you choose to pursue, you will be arriving as an apprentice in the middle of an ongoing conversation. Disciplines have complicated histories you can’t be expected to master overnight. But learning to recognize the long-standing binary oppositions in individual disciplines can help you make sense of the specific issues, themes, topics, and controversies you will encounter as a student and as a professional. Here are some very broadly stated examples of those binary oppositions.

| Discipline | Binary Oppositions (Binary A—Binary B) |

|---|---|

| Business | production—consumption |

| labor—capital | |

| Natural and applied sciences | empiricism—rationalism |

| observer—subject | |

| Social sciences | nature—nurture |

| free will—determinism | |

| Humanities | artist—culture |

| text—context |

These binary oppositions move freely from one discipline to another, often becoming more complicated as they do so. Consider a couple of examples:

- The binary opposition in the natural and applied sciences between empiricism (the so-called scientific method) and rationalism (using pure reason to speculate about one’s surroundings) originated as a debate in philosophy, a branch of the humanities. In the social sciences, in recent years, empirical data about brain functions in neuroscience have challenged rationalistic theories in psychology. Even disciplines in business are using increasingly empirical methods to study how markets work, as rationalist economic theories of human behavior increasingly come under question.

- The binary opposition between text and context in the humanities is borrowed from the social sciences. Instead of viewing texts as self-contained creations, scholars and artists in the humanities began to appreciate and foreground the cultural influences that helped shape those texts. Borrowings from business disciplines, such as economics and marketing, furthered the notion of a literary and artistic “marketplace,” while borrowings from the natural and applied sciences helped humanists examine more closely the relationship between the observer (whether the critic or the artist) and the subject (the text).

Of course, these two brief summaries vastly oversimplify the evolution of multiple disciplines over generations of intellectual history. Like the chart of binary oppositions, they’re meant merely to inspire you at this point to begin to note the connections between disciplines. Learning to think, write, and function in interdisciplinary ways requires practice that begins at the level of close reading and gradually expands into the way you interact with your surroundings as a college student and working professional.

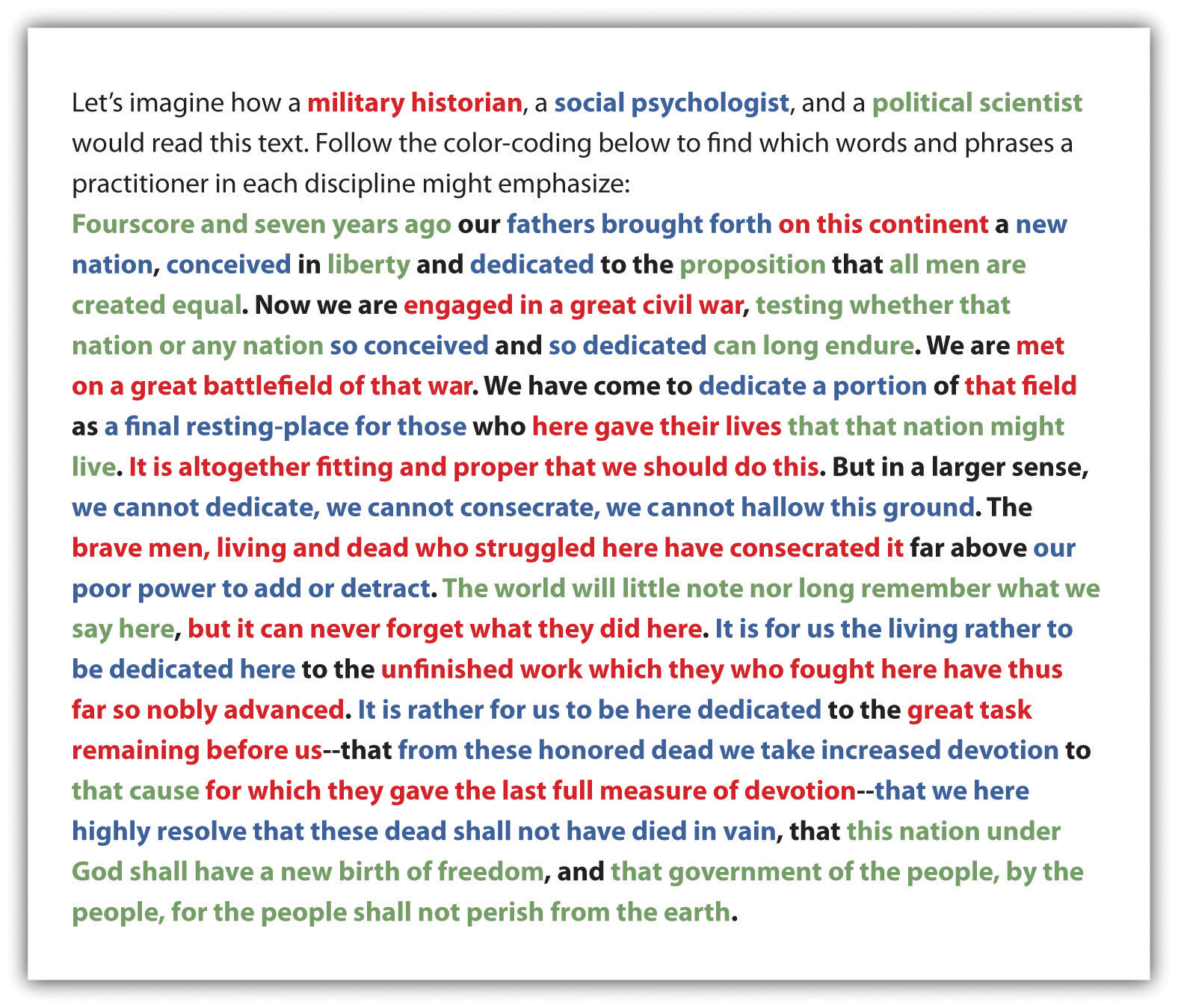

For a model of how to read and think through the disciplines, let’s draw on a short but very famous piece of writing (available through the Avalon Project in the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts”), Abraham Lincoln’s “Address at the Dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery,” composed and delivered in November of 1863, several months after one of the bloodiest battles in the American Civil War.

- A military historian (red passages) might focus on Lincoln’s rhetorical technique of using the field of a previous battle in an ongoing war (in this case a victory that nonetheless cost a great deal of casualties on both sides) as inspiration for a renewed, redoubled effort.

- A social psychologist (blue passages) might focus on how Lincoln uses this historical moment of unprecedented national trauma as an occasion for shared grief and shared sacrifice, largely through using the rhetorical technique of an extended metaphor of “conceiving and dedicating” a nation/child whose survival is at stake.

- A political scientist (green passages) might focus on how Lincoln uses the occasion as a rhetorical opportunity to emphasize that the purpose of this grisly and grim war is to preserve the ideals of the founders of the American republic (and perhaps even move them forward through the new language of the final sentence: “of the people, by the people, for the people”).

Notice that each reader, regardless of academic background, needs a solid understanding of how rhetoric works (something we’ll cover in Chapter 4 “Joining the Conversation” in more detail). Each reader has been trained to use a specific disciplinary lens that causes certain passages to rise to prominence and certain insights to emerge.

But the real power of disciplines comes when these readers and their readings interact with each other. Imagine how a military historian could use social psychology to enrich an understanding of how a civilian population was motivated to support a war effort. Imagine how a political scientist could use military history to show how a peacetime, postwar governmental policy can trade on the outcome of a battle. Imagine how a social psychologist could use political science to uncover how a traumatized social structure can begin to heal itself through an embrace of shared governance.

As Lincoln would say, “It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.”

Key Takeaways

- Disciplines have long-standing binary oppositions that help shape the terms of inquiry.

- To think, read, and write in a given discipline, you must learn to uncover binary oppositions in the texts, objects, and phenomena you are examining.

- Binary oppositions gain power and complexity when they are applied to multiple disciplines.

Exercises

- Following the Gettysburg Address example at the end of this section, use three disciplinary lenses to color-code a reading of your choice from the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader”.

- Find a passage in one of the textbooks you’re using in another course (or look over your lecture notes from another course) where the main discipline appears to be borrowing theories, concepts, or binary oppositions from other disciplines in order to produce new insights and discoveries.

- Individually or with a partner, set up an imaginary two-person dialogue of at least twenty lines (or two pages) that expresses two sides of a contemporary issue with equal force and weight. You may use real people if you want, either from your reading of specific columnists at Arts and Letters Daily or of the essayists at the Big Questions Essay Series (see the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader”). In a separate memo, indicate which side you lean toward personally and discuss any difficulty you had with the role playing required by this exercise.

- Show how one of the binary oppositions mentioned in this section is expressed by two writers in a discipline of your choosing. Alternatively, you can come up with a binary opposition of your own, backing it up with examples from the two extremes.

- Briefly describe how an insight or discovery applied past disciplinary knowledge to a new situation or challenge. How might you begin to think about addressing one of the contemporary problems in your chosen discipline?

Candela Citations

- License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright