Clark A. Pomerleau

October 1957 issue of The Ladder

In the face of Cold War hostility and McCarthyism, LGBTQ communities further institutionalized and began organizing a homophile movement for civil rights. Los Angeles gay men formed Mattachine Society in 1951. Founders Harry Hay, Bob Hull, and Chuck Rowland had organizing experience as US Communist Party members. They structured Mattachine into secret cells to survive government infiltration (D’Emilio, 1983, pp. 59-64). The founders blended Marxist theory that injustice and oppression were deeply embedded in societal structures with inspiring action from the African American Civil Rights Movement. They argued that repressive norms based in heterosexuality left homosexuals “‘largely unaware’ that they in fact constituted ‘a social minority imprisoned within a dominant culture.’” Founders sought to mobilize a large gay constituency through meetings and by creating homophile journals to produce a “new pride—a pride in belonging, a pride in participating in the cultural growth and the social achievements of…the homosexual minority” (D’Emilio, 1983, pp. 63-65; Kaiser, 1997, p. 123). Soon Mattachine grew to include many politically mainstream members who were anti-Communist. Founders stepped down in favor of leaders who argued that the mostly white, middle-class, gay members were the same as heterosexual citizens aside from private sphere love. They focused on gaining allies among heterosexual psychologists, clergymen, and public officials. Meanwhile, in San Francisco, Del Martin and Phillis Lyons’ group, Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), also “were fighting the church, the couch, and the courts” for equality. Like the more male-run Mattachine Review and One magazine, DOB’s journal, The Ladder, consistently assured lesbians of their worth as respectable middle-class people deserving treatment equal to heterosexuals (D’Emilio, 1983, p. 87; Gallo, 2006, p. 178). Chapters of both organizations spread to the East Coast and Midwest, forming a web of advocates for homosexual civil rights by the mid-1960s who published, lobbied, and picketed the White House and city governments for equality.

Watch

This interview with Mattachine Society founder Harry Hay, and Barbara Gittings, a founder of the Daughters of Bilitis and editor of The Ladder.

By then Black Civil Rights legal work and direct action produced court-ordered desegregation, anti-discrimination law, and voting rights, none of which overturned centuries of de facto housing segregation or educational and job discrimination that racialized poverty. Frustrations rose in poor communities of color over police brutality and the dearth of economic opportunities. In 1965, gay and lesbian street youth organized in San Francisco. They and trans women found Compton’s Cafeteria one of few places where they could meet. When Compton’s management called the police to deter drag queens and trans women’s patronage, a riot erupted. The next night trans hustlers and street people picketed against Compton’s and police brutality. Although the protest did not end abuse, collective militant queer resistance pushed the city to address their rights as citizens (Silverman and Stryker, 2005; Stryker, 2008, pp. 84-96).

Three years later the Stonewall Inn riot broke out due to a New York City police raid. This Mafia-run dive blackmailed gay Wall Street patrons and used those funds to pay off police. In return, police gave the Stonewall advanced warning of raids. Raids targeted those in full drag and trans sex workers like Sylvia Rivera. But raids could also ruin lives of white, Black, and Latino gay and lesbian customers; newspaper exposure led to being fired or evicted. On June 28, 1969 there was no tip off. Trans and lesbian patrons resisted—refusing to produce identification or to follow a female officer to the bathroom to verify their sex for arrest. They also objected to officers groping them (Carter, 2004, pp. 68, 80, 96-103, 124-5, 141, 156; Duberman, 1993, pp. 181-193). A growing crowd outside spontaneously responded to police violence by hurling coins and cans at officers who retreated into the bar. Rioting resumed a second and third night. Gay poet Allen Ginsberg heard slogans and crowed, “Gay power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country – 10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves” (Truscott, 1969, p. 18).

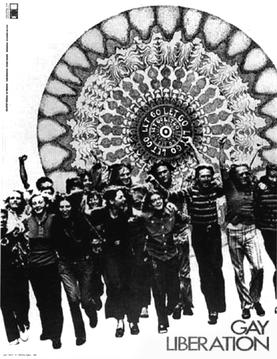

A poster used by the Gay Liberation Front in 1970.

The Stonewall Riot also did not stop police raids, but mainstream and gay coverage and leafleting spurred the creation of new, more militant gay organizing than previous homophile groups. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) sought to combine freedom from homophobia with a broader political platform that denounced racism and opposed capitalism. The Gay Activists Alliance rose from the GLF with confrontational “zaps” where they surprised politicians in public to force them to acknowledge gay and lesbian rights (Carter, 2004, pp. 245-246). Gay liberationists like Carl Wittman drew on past New Left anti-war student activism and the Women’s Liberation Movement. Wittman’s “Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto” (1970) rails against homophobia, imploring gays to free themselves by coming out while also acknowledging that will be too dangerous for some yet. Gay men must discard male chauvinism as antigay. Rather than “mimic” “straight society,” gay liberation should reject gender roles and marriage and embrace queens as having gutsily stood out. Wittman was attuned to the rise of lesbian feminism, which tied sexism together with homophobia. Lesbian feminists emphasized their focus on women’s autonomy and well-being rather than identification as mothers, wives, and daughters who indirectly gained from what benefitted men (Jay and Young, 1992; Pomerleau, 2010).

Gay liberationists continued the fight to overturn homophobia in religion, psychology, and law. Gay Catholics formed Dignity in 1969 (“Highlights”). The Unitarian Universalist Association urged an end to legal and social expressions of antigay discrimination in 1970, and the United Church of Christ ordained the first openly gay person in 1972. Integrity started in 1974 for Episcopalians. Mainstream Protestant denominations like the Presbyterian Church USA, United Methodist Church, and Lutheran Church in America endorsed decriminalization but still disapproved of homosexuality. Fundamentalist evangelicals became increasingly vocal among denominations opposed to same-sex relationships and gender nonconformity. They represented conservative religious organizing in response to progressive changes, propelling some religious right ministers to celebrity status such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Jim and Tammy Bakker. Some LGBT Christians flocked to Pentecostal minister Rev. Troy Perry. He founded the Metropolitan Community Church denomination from a house-based service in 1968. Meanwhile, Gay Jews in L.A. created the first gay synagogue in 1972 (Eaklor, 2008, p. 136). Gay-friendly or gay-run houses of worship proliferated over the decade, but the majority of LGBT Americans faced discrimination in unwelcoming religious congregations.

In addition to trying to integrate religious spaces, gay liberationists demonstrated against the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. Activists and gay counselors knew they were not sick. They marshalled psychological research homophile ally, Dr. Evelyn Hooker, created from 1957 on, that demonstrated gay men were equally stable as heterosexual men based on personality tests and sometimes showed more resilience (Minton, 2002, pp. 219-236). In 1973 the APA voted unanimously to define homosexuality in their diagnostic manual as “one form of sexual behavior, like other forms of sexual behavior which are not by themselves psychiatric disorders” (Eaklor, 2008, pp. 150-151). This was a major win on the long road to discrediting conversion therapies. Simultaneously, though, the APA’s third manual introduced “gender identity disorder of childhood” and “transsexualism” in 1980, preserving a concern about variety in gendered behavior and sustaining forced conversion programs for children and adolescents without increasing access to medical services some trans adults wanted.

Politically, the 1970s began fruitful efforts to gain equal rights ordinances and to elect lesbian and gay politicians. Elaine Noble joined the Massachusetts House in 1974, and Harvey Milk won in the San Francisco Board of Supervisors election in 1977 (Stein, 2012, p. 133). The conservative campaign of Anita Bryant that overturned Miami-Dade County, Florida’s gay rights ordinance in 1977 galvanized Christian Right conservatives and gay activists nationwide against or for extending equal rights regardless of sexual orientation. The next year activists managed to prevent California from passing an initiative that would have barred gay teachers from working in public schools. But cities with antigay campaigns experienced increased violence against gay and lesbian people and their businesses, centers, and churches, culminating in the murder of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone by former Board of Supervisors member and ex-policeman, Dan White. He served five years, convicted of manslaughter (Stein, 2012, pp. 140-141). Amid the volatile cultural fight of the 1970s, there were wins. By the end of the decade, activists had “decriminalized” themselves in just under half the nation by overturning twenty-two state sodomy statutes, had countered antigay city initiatives, and had convinced the Democratic Party to include a plank against sexual orientation-based discrimination in its 1980 platform (Eaklor, 2008, pp. 167, 182). They would have to wait until 2003 for the Supreme Court decision on Lawrence v. Texas to strike down sodomy laws nationwide.

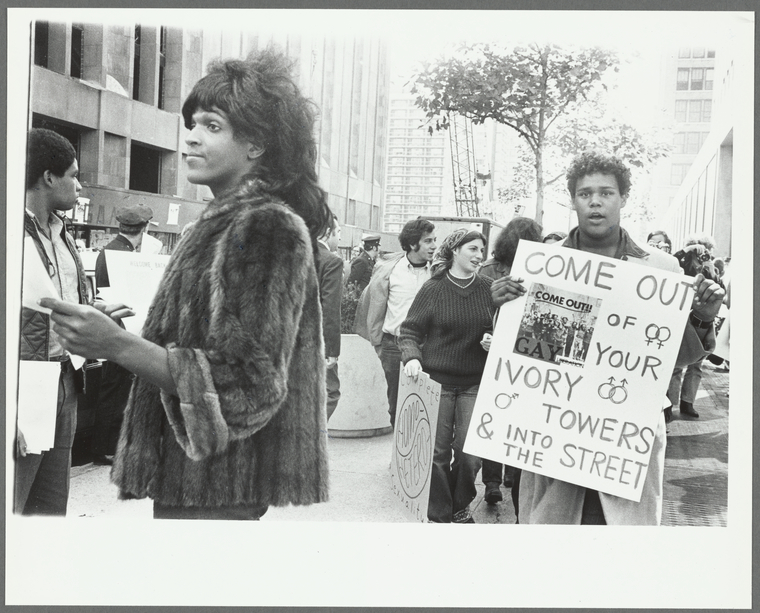

Marsha P. Johnson hands out flyers for support of gay students at N.Y.U.

The 1970s saw a cultural renaissance of LGBT institution building and cultural productions through publishing and music. More Americans came out despite the real hazards of family rejection, violence, and legal discrimination. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson survived such dangers to start Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970. STAR, the first trans woman of color led organization, created the first homeless queer youth and sex worker shelter in North America. By recognizing links among homophobia, transphobia, racism, and classism, STAR filled needs other early gay liberation groups were not considering. More often gay and lesbians organized safe spaces through bars, gay baths, bookstores, discos, sports leagues, and musical ensembles (Eaklor, 2008, pp. 132-136). As the 1970s continued, feminist lesbians of color took the lead in how crucial was “the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (Combahee, 1978, pp. 210).

Watch

Billy Porter giving a brief history of queer political action

Candela Citations

- U.S. LGBTQ History. Authored by: Clark A. Pomerleau. Provided by: University of North Texas. Project: LGBTQ Studies. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- GLF Poster. Provided by: Gay Liberation Front. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gay_liberation_1970_poster.jpg. License: Other

- A Brief History of Forgotten Queer Political Action with Billy Porter. Authored by: them. Provided by: Youtube. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XoXH-Yqwyb0. License: All Rights Reserved

- Marsha P. Johnson hands out flyers in support of Gay students' rights at NYU's Weinstein Hall.GLF Demo.. Authored by: Diana Davies. Provided by: New York Public Library Digital Collections. Located at: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-57b0-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. License: All Rights Reserved

- The Ladder. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://Harry%20Hay,%20a%20founder%20of%20the%20Mattachine%20Society%20and%20the%20Radical%20Faeries;%20and%20Barbara%20Gittings,%20a%20founder%20of%20the%20Daughters%20of%20Bilitis,%20editor%20of%20The%20Ladder. License: All Rights Reserved

- Vito Russo interviews Harry Hay and Barbara Gittings (1 of 2). Authored by: BettyByte. Provided by: Youtube. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RSO5Y8fGac4. License: All Rights Reserved