Lynne Stahl

Camp

Susan Sontag, cultural critic and author of “Notes on Camp.”

Amid the post-World War II baby boom, 1940s-50s suburban America projected an idyllic image of the nuclear family: suburban homes with white picket fences, father as breadwinner, stay-at-home mom. This image and its performative “American-ness” became the target of parody and critique by dissidents, filmmakers prime among them. One manifestation of such dissent came to be known as camp.

Camp is an aesthetic that privileges “poor taste,” shock value, and irony, intentionally challenging the traditional attributes of high art. It is often characterized by showiness, extreme artifice, and tackiness—e.g. the popular pink flamingo lawn ornaments from which John Waters’ iconic film takes its name. While largely ironic, camp can also devolve from earnestness gone awry, as in attempts at profundity that fall absurdly short of their targets; Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995) and Steven Antin’s Burlesque (2010) exemplify the latter. In “Notes on Camp,” cultural critic Susan Sontag observes that camp “sees everything in quotation marks,” and that “nothing in nature can be campy. . . to perceive camp in objects is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role” (1990, p. 275). This notion reflects the same logic that would later structure many key tenets of queer theory, particularly the idea that all gender is performance, consciously or otherwise, and that sex, gender, and sexuality and the relationships there among are products of artifice rather than nature.

John Waters

Since the 1960s, the camp cinema of John Waters has delighted some audiences while repulsing others. Pink Flamingos (1972), Polyester (1981), and Hairspray (1988) lampoon the strictures and hypocrisies of the suburban US, featuring the drag queen Divine and innumerable acts of subversion. Divine’s influence went far beyond Waters’ films, too; legend holds Divine to be the inspiration for the villainous sea witch Ursula in Disney’s The Little Mermaid (1992). More recently, Liz Flahive and Carly Mensch’s comedy series GLOW (2017-) has embraced the campy ‘80s phenomenon of the same name, giving fictional life to the erstwhile women’s wrestling venture full of caricatured personae and self-consciously over-the-top storylines.

TRANSITION: New Queer Cinema

The rise of independent film festivals such as Sundance and Telluride in the 1970s and ‘80s spotlighted smaller productions that lacked the financial backing of major studios, from avante-garde work to indie narrative cinema. Following the liberation-oriented activism of the 1970s-80s and amid the HIV/AIDS crisis, a movement of unconventional, experimental, and unapologetic films emerged in the early 1990s. Rich termed this movement “New Queer Cinema,” describing it as one “favoring pastiche and appropriation, influenced by art, activism, and such new entities as music video . . . It reinterpreted the link between the personal and the political envisioned by feminism [and] restaged the defiant activism pioneered at Stonewall” (2013, p. xv).

Cheryl Dunye presenting The Watermelon Woman at SFMOMA in San Francisco, California.

NQC films such as Gus van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991) and Derek Jarman’s Edward II (1991) featured overtly queer content, often focalized through outsider characters. Many also engaged with or alluded to the AIDS crisis: Richard Fung’s 1991 Chinese Characters, Marlon Riggs’s 1989 Tongues Untied, Todd Haynes’s 1991 Poison and 1995 Safe, and Gregg Araki’s 1992 The Living End.

Cheryl Dunye’s mockumentary The Watermelon Woman (1996) calls out the erasure of Black lesbians in Hollywood and the persistence of racist film tropes over the years. The film follows Dunye’s character as she stages interviews with both fictitious and real-life lesbian activists including Sarah Schulman and Camille Paglia. Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning (1990) documents New York City ball culture, foregrounding Black and Latinx lives and communities involved in the vogue scene. Iconic as it has become, scholars including bell hooks and Judith Butler have questioned its racial politics—Livingston is white and from a privileged background, profiting through a marginalized community—and unambivalent celebration of drag as a means of subversion and liberation. Critiques notwithstanding, Steven Canals, Brad Falchuk, and Ryan Murphy joined forces to create Pose (2018-), an FX series that draws from Paris is Burning in its fictionalized representation of the same ballroom culture. Livingston has contributed in directorial and production roles.

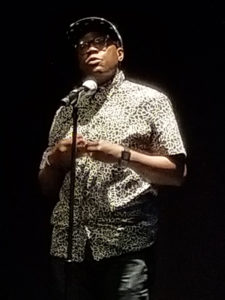

Barry Jenkins, the director of Moonlight, the 2016 Best Picture winning film that details the coming of age of a Black gay man, Chiron.

Mainstream Gay?

While New Queer Cinema was defined largely by the queer-identified directors, writers, and producers creating its films, LGBTQ films began to enter bigger markets in the 2000s. Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005), for example, featured (straight) A-list stars Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal as covert lovers. Subsequently, films such as Julie Taymor’s Frida (2002), Lisa Cholodenko’s The Kids are All Right (2010), Ryan Murphy’s The Normal Heart (2014), Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game (2014), and Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight (2016) have all featured well-known (and disproportionately straight) actors and achieved mainstream prominence, including major award nominations.