Jennifer Miller

Jose Esteban Muñoz’s hope affirming work claims the future for queers (2009). He writes: “The future is queerness’s domain. Queerness is a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present” (2009, 1). For Muñoz, conditions of everyday life are simply not viable for queer people of color who must work to imagine a transformed world. In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, Muñoz explores “the critical imagination,” transformative thought that can prompt and shape social change. This idea, along with Muñoz’s intersectional theorization of oppression and social transformation, resonates with many other queer theorists and will be foregrounded in this section.

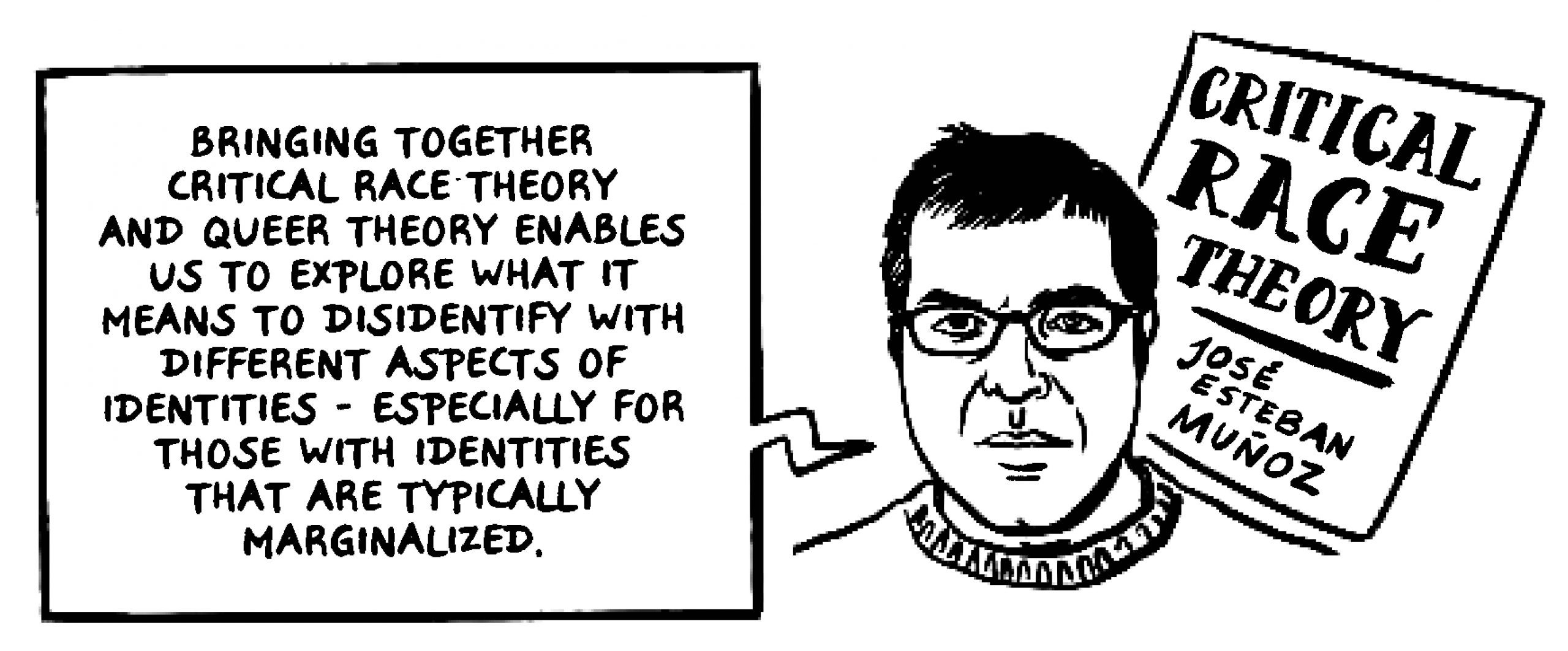

Jose Esteban Muñoz (From Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker and Jules Scheele, provided courtesy of Icon Books. Copyright Icon Books, reprinted with permission.)

Activist Charlene A. Carruthers recent publication, Unapologetic: A Black Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements, foregrounds the importance of intersectional thinking. She introduces the idea of a “Black queer feminist lens,” which she describes as a lens “through which people and groups see to bring their full selves into the process of dismantling all systems of oppression” (2018, 10). Whereas libertarian, conservative, and even liberal lesbian and gay groups seek to diminish the importance of sexual (and other) differences, Carruthers suggests that bringing a Black queer feminist lens to political thought and praxis renounces the middle-class notion of the public sphere as a place where identity should be abandoned to maintain the myth universality (2018, 10). Even more, her vision of activism decenters queerness; she demands that multiple types of oppression, types that will not be experienced the same way or even at all by the entire LGBT community, must be acknowledged.

Like Muñoz, Carruthers foregrounds the importance of the Black imagination, specifically the ability to imagine “alternative economics, alternative family structures, or something else entirely” (2018, 39). This work cannot be accomplished if groups like the HRC, with a clear pro-capitalist agenda and confidence in the superiority of the nuclear family shape public discourse about LGBTQ issues, which is why scholars like Duggan and Puar have taken on establishment gay and lesbian rights groups in their scholarship.

In his recent publication, After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life, Joshua Chambers-Letson explores the effect music and art can have on audiences. He suggests that creative work can expand imaginative possibilities and prompt new modes of being together in the world. His project explores “the ways minoritarian subjects mobilize performance to survive the present, improvise new worlds, and sustain new ways of being in the world” (2018, 4–5).

Similar to Muñoz and Carruthers, he argues that radical transformation is the only way forward for queers of color. Instead of asking, how can we include queers in the existing social world, his project asks, how can we queer the existing social world to make it habitable by queers?

Additionally, like Carruthers, Chambers-Letson decenters the queer sexual subject as well as queer theory to explore intersectional possibilities for speculative world making and practical activism. For him, experiencing performance allows audiences to rehearse new ways of seeing and being in the world together, which is why he foregrounds the importance of art a music. Importantly, Chambers-Letson does not see art and performance as able to fulfill the promise of revolutionary transformative change; instead, it is a site where possible worlds are imagined, but they must still be materially enacted (2018, 33).

Candela Citations

- Thirty Years of Queer Theory. Authored by: Jennifer Miller. Provided by: University of Texas at Arlington. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-lgbtq-studies. License: CC BY: Attribution