Unfortunately for Jackson’s Democrats (and most other Americans), their victory over the Bank of the United States worsened rather than solved the country’s economic problems.

For a while, to be sure, the signs were good. Between 1834 and 1836, a combination of high cotton prices, freely available foreign and domestic credit, and an infusion of specie (“hard” currency in the form of gold and silver) from Europe spurred a sustained boom in the American economy. At the same time, sales of western land by the federal government promoted speculation and poorly regulated lending practices, creating a vast real estate bubble.

Meanwhile, the number of state-chartered banks grew from 329 in 1830 to 713 just six years later. As a result, the volume of paper banknotes per capita in circulation in the United States increased by forty percent between 1834 and 1836. Low interest rates in Great Britain also encouraged British capitalists to make risky investments in America. British lending across the Atlantic surged, raising American foreign indebtedness from $110 to $220 million over the same two years.

As the boom accelerated, banks became more careless about the amount of hard currency they kept on hand to redeem their banknotes. And although Jackson had hoped that his bank veto would reduce bankers’ and speculators’ power over the economy, it actually made the problems worse.

Two further federal actions late in the Jackson administration also worsened the situation. In June 1836, Congress decided to increase the number of banks receiving federal deposits. This plan undermined the banks that were already receiving federal money, since they saw their funds distributed to other banks. Next, seeking to reduce speculation on credit, the Treasury Department issued an order called the Specie Circular in July 1836, requiring payment in hard currency for all federal land purchases. As a result, land buyers drained eastern banks of even more gold and silver.

By late fall in 1836, America’s economic bubbles began to burst. Federal land sales plummeted. The New York Herald reported that “lands in Illinois and Indiana that were cracked up to $10 an acre last year, are now to be got at $3, and even less.” The newspaper warned darkly, “The reaction has begun, and nothing can stop it.”

Runs on banks began in New York on May 4, 1837, as panicked customers scrambled to exchange their banknotes for hard currency. By May 10, the New York banks, running out of gold and silver, stopped redeeming their notes. As news spread, banks around the nation did the same. By May 15, the largest crowd in Pennsylvania history had amassed outside of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, denouncing banking as a “system of fraud and oppression.”

The Panic of 1837 led to a general economic depression. Between 1839 and 1843, the total capital held by American banks dropped by forty percent as prices fell and economic activity around the nation slowed to a crawl. The price of cotton in New Orleans, for instance, dropped fifty percent.

Travelling through New Orleans in January 1842, a British diplomat reported that the country “presents a lamentable appearance of exhaustion and demoralization.” Over the previous decade, the American economy had soared to fantastic new heights and plunged to dramatic new depths.

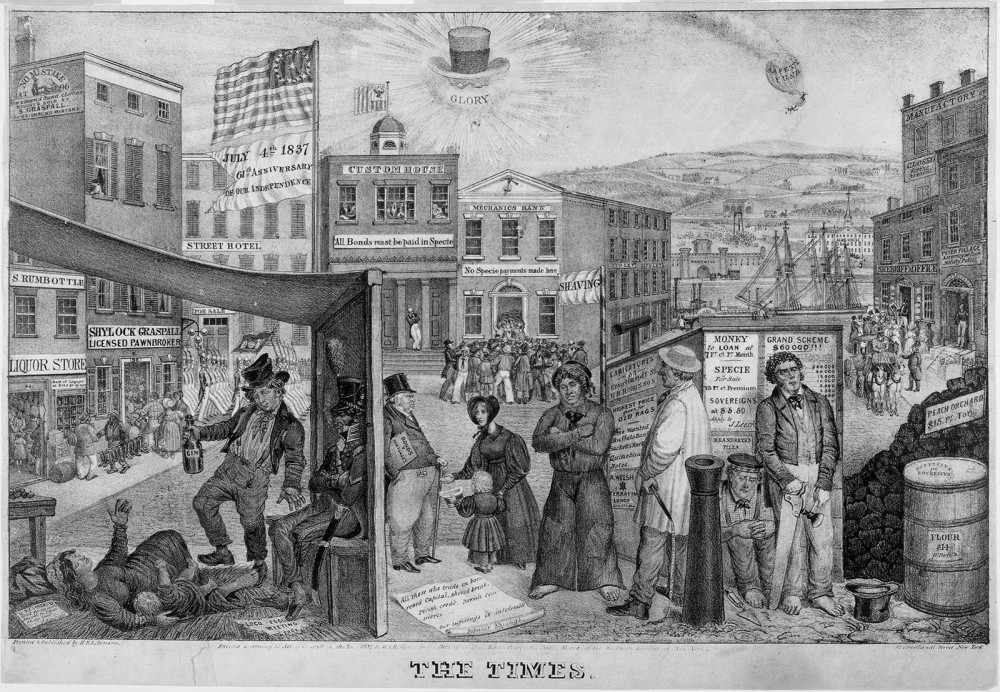

Many Americans blamed the Panic of 1837 on the economic policies of Andrew Jackson, who is sarcastically represented in the lithograph as the sun with top hat, spectacle, and a banner of “Glory” around him. The destitute people in the foreground (representing the common man) are suffering while a prosperous attorney rides in an elegant carriage in the background (right side of frame). Edward W. Clay, “The Times,” 1837. Wikimedia.

Normal banking activity did not resume around the nation until late 1842. Meanwhile, two hundred banks closed, cash and credit became scarce, prices declined, and trade slowed. During this downturn, seven states and a territorial government defaulted on loans made by British banks to finance internal improvements.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike