Learning Objectives

- Describe sociology and some of its central concepts

Figure 1. Sociologists learn about society as a whole while studying one-to-one and group interactions. (Photo courtesy of Gareth Williams/flickr)

What Are Central Concepts in Sociology?

Sociology is the study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions. A group is any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity. A group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture is what sociologists call a society.

Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society. Sociologists working from the micro-level study small groups and individual interactions, while those using macro-level analysis look at trends among and between large groups and societies. For example, a micro-level study might look at the accepted rules of conversation in various groups such as among teenagers or business professionals. In contrast, a macro-level analysis might research the ways that language use has changed over time or in social media outlets.

The term culture refers to the group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from routine, everyday interactions to the most important parts of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including all of the social rules. Sociologists often study culture using the sociological imagination, which pioneer sociologist C. Wright Mills described as an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shaped the person’s choices and perceptions. It is a way of seeing our own and other people’s behavior in relation to history and social structure (1959).

One illustration of this is a person’s decision to marry. In the United States, this choice is heavily influenced by individual feelings; however, the social acceptability of marriage relative to the person’s circumstances also plays a part. It is important to remember that culture is produced by the people in a society, and therefore sociologists take care not to treat the concept of “culture” as though it were alive in its own right. Reification is the term used to describe this mistaken tendency, where one treats an abstract concept as though it has a real, material existence (Sahn 2013).

Try It

Watch It

Throughout this course, you will encounter video clips that explain and reiterate key concepts from the reading. They are strongly recommended. Please take the time to watch the videos. The following video gives an introduction to sociology and will give you a preview of many concepts that will be covered in the course.

Studying Patterns: How Sociologists View Society

All sociologists are interested in the experiences of individuals and how those experiences are shaped by interactions with social groups and society as a whole. To a sociologist, the personal decisions an individual makes do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns and social forces put pressure on people to select one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behavior of large groups of people living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures.

Figure 2. Modern U.S. families may be very different in structure from what was historically typical. (Photo courtesy of Tony Alter/Wikimedia Commons)

Changes in the U.S. family structure offer an example of patterns that sociologists are interested in studying. A “typical” family is now quite different than in past decades when most U.S. families consisted of married parents living in a home with their unmarried children. The percentage of unmarried couples, same-sex couples, single-parent and single-adult households is increasing, as is the number of expanded households, in which extended family members such as grandparents, cousins, or adult children live together in the family home (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

While mothers still make up the majority of single parents, millions of fathers are also raising their children alone, and more than 1 million of these single fathers have never been married (Williams Institute 2010; cited in Ludden 2012). Increasingly, single men and women and cohabiting opposite-sex or same-sex couples are choosing to raise children outside of marriage through surrogates or adoption.

Sociologists study social facts, which are aspects of social life that shape a person’s behavior. How do social facts affect U.S. family structures? These can include the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and all of the cultural rules that govern social life. These all may contribute to changes in the U.S. family structure. Do people in the United States view marriage and family differently than in earlier periods? Do employment status and economic conditions play a role? How has culture influenced the choices that individuals make in living arrangements?

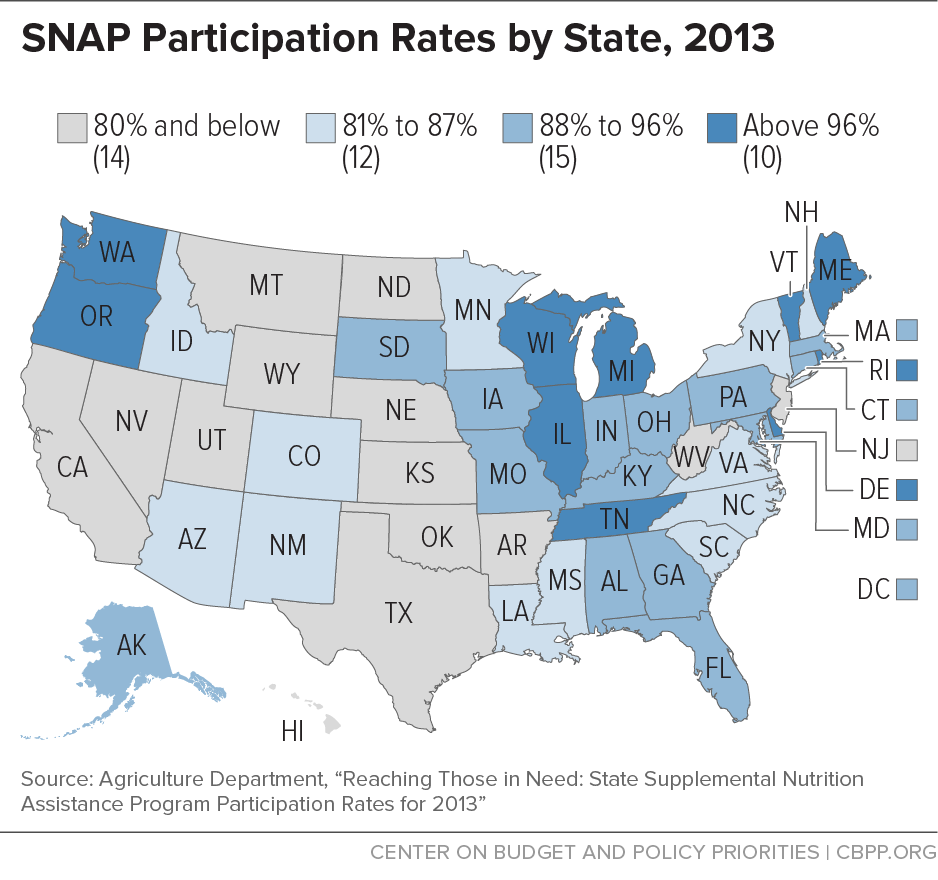

Sociologists are studying the consequences of these new patterns, such as the ways children are affected by them or by changing needs for education, housing, and healthcare. An example of the way society influences individual decisions can be seen in people’s opinions about and use of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP benefits. Some people believe those who receive SNAP benefits are lazy and unmotivated, though statistics from the United States Department of Agriculture show a more complex picture.

Figure 3. Percentage of eligible people who participate in SNAP.

To identify social trends, sociologists studied how some people use SNAP benefits and how other people react to their use. Research has found that for many people from all classes, there is a strong stigma, or an attribute that is deeply discrediting (Goffman 1963), attached to the use of SNAP benefits. This stigma can prevent people who qualify for this type of assistance from using the benefits. According to Hanson and Gundersen (2002), how strongly this stigma is felt is linked to the general economic climate. This illustrates how sociologists observe a pattern in society. The percentage of the population receiving SNAP benefits is much higher in certain states than in others. Does this mean, if the stereotype above were applied, that people in some states are lazier and less motivated than those in other states? Sociologists study the economies in each state—comparing unemployment rates, food, energy costs, and other factors—to explain differences in social issues like this. Sociologists identify and study patterns related to all kinds of contemporary social issues. The “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy regarding gay and lesbian service members, the emergence of the Tea Party political faction, how Twitter has influenced everyday communication—these are all examples of topics that sociologists might explore.

Studying Part and Whole: How Sociologists View Social Structures

A key premise of the sociological imagination is the concept that the individual and society are inseparable. It is impossible to study one without the other. German sociologist Norbert Elias called the process of simultaneously analyzing the behavior of individuals and the society that shapes that behavior figuration. An application that makes this concept understandable is the practice of religion. While people experience their religions in a distinctly individual manner, religion exists in a larger social context. For instance, an individual’s religious practice may be influenced by governmental authority, traditional holidays, educational institutions, places of worship, well-established rituals, and so on. These influences underscore the important relationship between individual practices of religion and the social pressures that influence that religious experience (Elias 1978).

Individual-Society Connections

When sociologist Nathan Kierns spoke to his friend Ashley (a pseudonym) about the move she and her female partner had made from an urban center to a small Midwestern town, he was curious about how the social pressures placed on a lesbian couple differed from one community to the other. Ashley said that in the city they had been accustomed to getting looks and hearing comments when she and her partner walked hand in hand. Otherwise, she felt that they were at least being tolerated. There had been little to no outright discrimination. Things changed when they moved to the small town for her partner’s job. For the first time, Ashley found herself experiencing direct discrimination because of her sexual orientation. Some of it was particularly hurtful. Landlords would not rent to them. Ashley, who is a highly trained professional, had a great deal of difficulty finding a new job.

When Nathan asked Ashley if she and her partner became discouraged or bitter about this new situation, Ashley said that rather than letting it get to them, they decided to do something about it. Ashley approached groups at a local college and several churches in the area. Together they decided to form the town’s first gay-straight alliance. The alliance has worked successfully to educate their community about same-sex couples. It also worked to raise awareness about the kinds of discrimination that Ashley and her partner experienced in the town and how those could be eliminated. The alliance has become a strong advocacy group, and it is working to attain equal rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LBGT individuals. Kierns observed that this is an excellent example of how negative social forces can result in a positive response from individuals to bring about social change (Kierns 2011).

Try It<

Think It Over

- What do you think C. Wright Mills meant when he said that to be a sociologist, one had to develop a sociological imagination?

- Describe a situation in which a choice you made was influenced by societal pressures.

Glossary

- culture:

- a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs

- figuration:

- the process of simultaneously analyzing the behavior of an individual and the society that shapes that behavior

- group:

- any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity

- reification:

- an error of treating an abstract concept as though it has a real, material existence

- society:

- a group of people who live in a defined geographical area who interact with one another and who share a common culture

- sociological imagination:

- the ability to understand how your own past relates to that of other people, as well as to history in general and societal structures in particular

- sociology:

- the systematic study of society and social interaction

Candela Citations

- What Is Sociology? Crash Course Sociology #1. Provided by: CrashCourse. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnCJU6PaCio. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- What is Sociology?. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/AgQDEnLI@11.2:XZe6d2Jr@11/What-Is-Sociology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@3.49

- SNAP participation by state. Authored by: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Located at: http://www.cbpp.org/snap-participation-rates-by-state-2013. License: All Rights Reserved