Learning Objectives

- Describe the abolitionist movement in the early to mid-nineteenth century

- Explain contributions to the abolitionist movement by influential leaders like William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass

William Lloyd Garrison and Abolitionist Activism

William Lloyd Garrison’s early life and career famously illustrated the transition toward immediatism among radical Christian reformers, who advocated the immediate and complete emancipation of all enslaved people in the U.S. As a young man immersed in the reform culture of antebellum Massachusetts, Garrison had fought slavery in the 1820s by advocating for both black colonization and gradual abolition. Fiery tracts penned by black northerners David Walker and James Forten, however, convinced Garrison that African Americans possessed a hard-won right to the fruits of American liberty and he began to call for more radical tactics and solutions to the problem of slavery.

Although William Lloyd Garrison had once been in favor of colonization, he came to believe that such a scheme only deepened racism and perpetuated the sinful practices of his fellow Americans. So, in 1831, he established a newspaper called The Liberator, through which he organized and spearheaded an unprecedented interracial crusade dedicated to promoting immediate emancipation and black citizenship. The first edition declared:

I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen;—but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.

Figure 1. These woodcuts of a chained and pleading slave, Am I Not a Man and a Brother? (a) and Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?, accompanied abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier’s antislavery poem, “Our Countrymen in Chains.” Such images exemplified moral suasion: showing with pathos and humanity the moral wrongness of slavery.

Then, in 1833, Garrison presided as reformers from ten states came together to create the American Antislavery Society. They rested their mission for immediate emancipation “upon the Declaration of our Independence, and upon the truths of Divine Revelation,” binding their cause to both national and Christian redemption. These predominately White, middle-class, northern Christian reformers saw the cause of abolition as not only fighting for the salvation of enslaved people but also for the soul of the nation.

White Virginians blamed Garrison for stirring up slaves and instigating slave rebellions like Nat Turner’s. Garrison founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1831, and the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in 1833. By 1838, the AASS had 250,000 members, sometimes called Garrisonians. They rejected colonization as a racist scheme and opposed the use of violence to end slavery. Influenced by evangelical Protestantism, Garrison and other abolitionists believed in moral suasion, which relied on dramatic narratives, often from former enslaved persons, about the horrors of slavery. They argued that slavery destroyed families, as children were sold and taken away from their mothers and fathers. Moral suasion resonated with many women, who condemned the sexual violence against enslaved women and the victimization of southern White women by adulterous husbands.

Link to Learning

Read the full text of John Greenleaf Whittier’s antislavery poem “Our Countrymen in Chains.”

What imagery and rhetoric does Whittier use to advance the cause of abolitionism?

Garrison wrote of equal rights and demanded that blacks be treated as equal to Whites. He appealed to women and men, Black and White, to join the fight. The abolitionist press, which produced hundreds of tracts, helped to circulate arguments of moral suasion. Garrison and other abolitionists also used the power of petitions, sending hundreds of petitions to Congress in the early 1830s, demanding an end to slavery. Since most newspapers published congressional proceedings, the debate over abolition petitions reached readers throughout the nation.

Try It

In order to accomplish their goals, abolitionists employed every method of outreach and agitation used in the social reform projects of the benevolent empire. At home in the North, abolitionists established hundreds of antislavery societies and worked with long-standing associations of Black activists to establish schools, churches, and voluntary associations. Women and men of all colors were encouraged to associate together in these spaces to combat what they termed “color phobia.” Harnessing the potential of steam-powered printing and mass communication, abolitionists also blanketed the free states with pamphlets and antislavery newspapers. They blared their arguments from lyceum podiums and broadsides. Prominent individuals such as Wendell Phillips and Angelina Grimké saturated northern media with shame-inducing exposés of northern complicity in the return of fugitive enslaved persons, and White reformers sentimentalized slave narratives that tugged at middle-class heartstrings, such as Sojourner Truth’s memoirs and the fictional novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Abolitionists used the United States Postal Service in 1835 to inundate southern enslavers with calls to emancipate their enslaved persons in order to save their souls, and, in 1836, they prepared thousands of petitions for Congress as part of the “Great Petition Campaign.” In the six years from 1831 to 1837, abolitionist activities reached dizzying heights.

Opposition to Abolition

However, such efforts encountered fierce opposition, as most Americans did not share abolitionists’ particular brand of nationalism. In fact, abolitionists remained a small, marginalized group detested by most White Americans in both the North and the South. Immediatists were attacked as the harbingers of disunion, rabble-rousers who would stir up sectional tensions and thereby imperil the American experiment of self-government. Fearful of disunion and outraged by the interracial nature of abolitionism, northern mobs smashed abolitionist printing presses and even killed a prominent antislavery newspaper editor named Elijah Lovejoy. White southerners, believing that abolitionists had incited Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, aggressively purged antislavery dissent from the region. On the ground, abolitionists’ personal safety was threatened by violent harassment. In the halls of congress, Whigs and Democrats joined forces in 1836 to pass an unprecedented restriction on freedom of political expression known as the gag rule, which prohibited all discussion of abolitionist petitions in the House of Representatives.

Varying Opinions on Abolition

In the face of such substantial external opposition, the abolitionist movement began to splinter. In 1839, an ideological schism shook the foundations of organized antislavery. Moral suasionists, led most prominently by William Lloyd Garrison, felt that the United States Constitution was a fundamentally pro-slavery document, and that the present political system was irredeemable. They dedicated their efforts exclusively towards persuading the public to redeem the nation by re-establishing it on antislavery grounds. However, many abolitionists, reeling from the level of entrenched opposition met in the 1830s, began to feel that moral suasion was no longer realistic. Instead, they believed, abolition would have to be effected through existing political processes. So, in 1839, political abolitionists split from Garrison’s American Antislavery, forming the Liberty Party under the leadership of James G. Birney. Born in Kentucky in 1792, Birney owned slaves and, searching for a solution to what he eventually condemned as the immorality of slavery, initially endorsed colonization. In the 1830s, however, he rejected colonization, freed his enslaved persons, and began to advocate the immediate end of slavery. The Liberty Party was predicated on the belief that the U.S. Constitution was actually an antislavery document that could be used to abolish the stain of slavery through the national political system. The Liberty Party did not generate much support and remained a fringe third party. Many of its supporters turned to the Free-Soil Party in the aftermath of the Mexican Cession.

The vast majority of northerners rejected abolition entirely. Indeed, abolition generated a fierce backlash in the United States, especially during the Age of Jackson, when racism saturated American culture. Anti-abolitionists in the North saw Garrison and other abolitionists as the worst of the worst, a threat to the republic that might destroy all decency and order by upending time-honored distinctions between Blacks and Whites, and between women and men. Northern anti-abolitionists feared that if slavery ended, the North would be flooded with blacks who would take jobs from Whites and exacerbate many of the social issues like poverty and urban overcrowding that reformers sought to alleviate.

Opponents made clear their resistance to Garrison and others of his ilk; Garrison nearly lost his life in 1835, when a Boston anti-abolitionist mob dragged him through the city streets. Anti-abolitionists tried to pass federal laws that made the distribution of abolitionist literature a criminal offense, fearing that such literature, with its engravings and simple language, could spark more violent revolts like Nat Turner’s. Their sympathizers in Congress passed a “gag rule” that forbade the consideration of the many hundreds of petitions sent to Washington by abolitionists. A mob in Illinois killed abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy in 1837, and the following year, ten thousand protestors destroyed the abolitionists’ newly built Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, burning it to the ground.

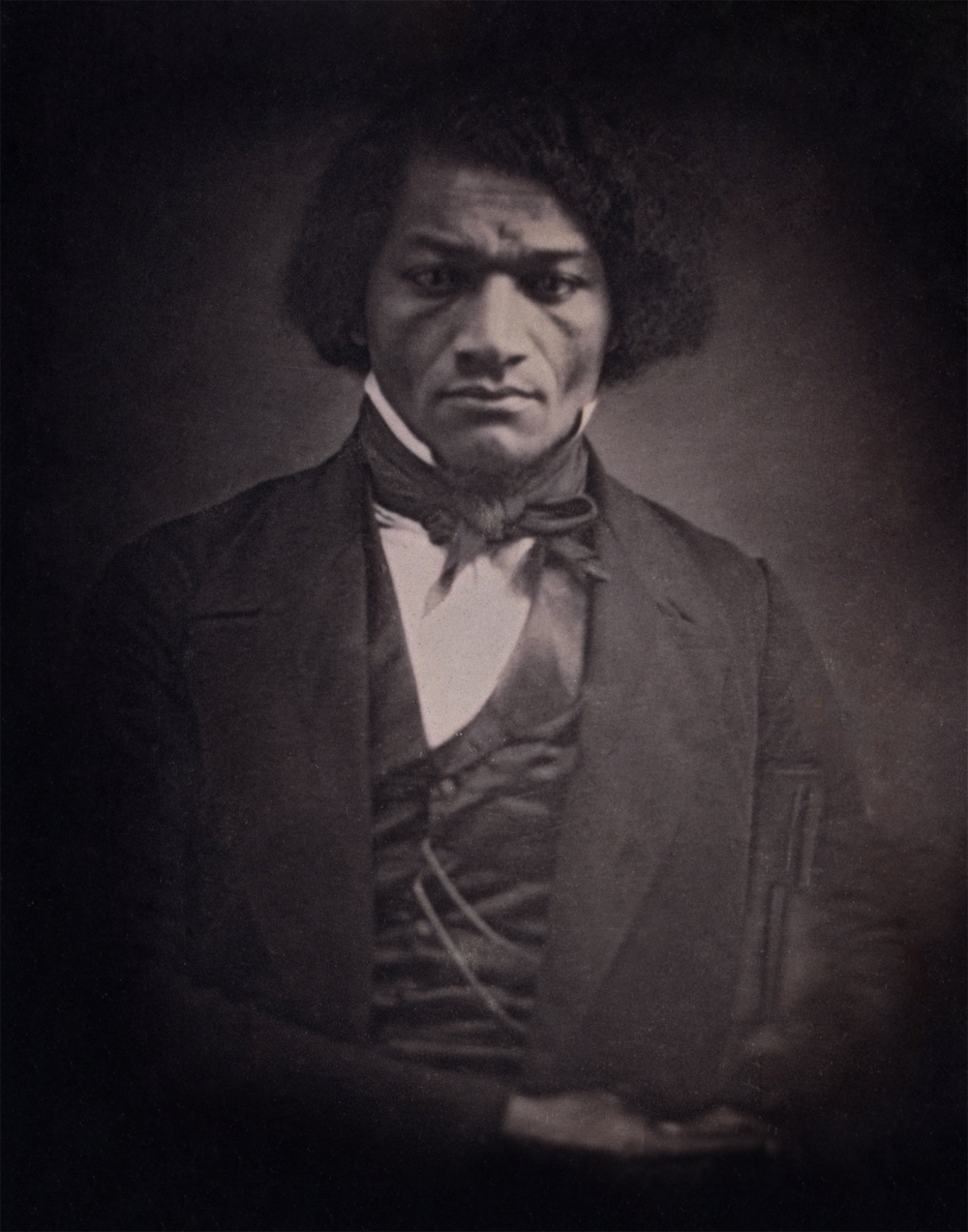

Figure 2. Frederick Douglass was perhaps the most famous African American abolitionist, fighting tirelessly not only for the end of slavery but for equal rights of all American citizens. This copy of a daguerreotype shows him as a young man, around the age of 29 and soon after his self-emancipation. Print, c. 1850 after c. 1847 daguerreotype.

Significantly, abolitionist factions also disagreed on the issue of women’s rights. Many abolitionists who believed full-heartedly in moral suasion nonetheless felt compelled to leave the American Antislavery Association because it elevated women to leadership positions and endorsed women’s suffrage. The more conservative members saw this as evidence that, in an effort to achieve general perfectionism, the American Antislavery Society had lost sight of its most important goal. Under the leadership of Arthur Tappan, they left to form the American and Foreign Antislavery Society. Though these disputes were ultimately mere road bumps on the long path to abolition, they did become so bitter and acrimonious that former friends cut social ties and traded public insults.

Another significant shift stemmed from the disappointments of the 1830s. Abolitionists in the 1840s increasingly moved from agendas based on reform to agendas based on resistance. While moral suasionists continued to appeal to hearts and minds, and political abolitionists launched sustained campaigns to bring abolitionist agendas to the ballot box, the entrenched and violent opposition of enslavers and the northern public to their reform efforts encouraged abolitionists to focus on other avenues of fighting the politically and economically entrenched slave power. For example, abolitionists increasingly focused on helping and protecting runaway enslaved persons, and on establishing international antislavery support networks to help put foreign political pressure on the United States to abolish the institution.

Frederick Douglass is one prominent example of how these two trends came together. Douglass was born in Maryland in 1818, escaping to New York in 1838. He later moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, with his wife. Douglass’s commanding presence and powerful speaking skills electrified his listeners when he began to provide public lectures on slavery. He came to the attention of Garrison and others, who encouraged him to publish his story. In 1845, Douglass published Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Written by Himself, in which he told about his life of slavery in Maryland. He identified by name the Whites who had brutalized him, and for that reason, along with the mere act of publishing his story, Douglass had to flee the United States to avoid being murdered. His first autobiography was so widely read that it was reprinted in nine editions and translated into several languages.

Figure 3. This 1856 ambrotype of Frederick Douglass (a) demonstrates an early type of photography developed on glass. Douglass was an escaped enslaved person who was instrumental in the abolitionist movement. His slave narrative, told in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Written by Himself (b), followed a long line of similar narratives that demonstrated the brutality of slavery for northerners unfamiliar with the institution.

British abolitionist friends bought his freedom from his Maryland owner, and Douglass returned to the United States. He began to publish his own abolitionist newspaper, North Star, in Rochester, New York. During the 1840s and 1850s, Douglass labored to bring about the end of slavery by telling the story of his life and highlighting how slavery destroyed families, both Black and White.

Frederick Douglass on Slavery

Most White enslavers frequently raped female enslaved persons. In this excerpt, Douglass explains the consequences for the children fathered by White masters and enslaved women.

Slaveholders have ordained, and by law established, that the children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers . . . this is done too obviously to administer to their own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable . . . the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father. . . .

Such slaves [born of white masters] invariably suffer greater hardships . . . They are . . . a constant offence to their mistress . . . she is never better pleased than when she sees them under the lash, . . . The master is frequently compelled to sell this class of his slaves, out of deference to the feelings of his white wife; and, cruel as the deed may strike any one to be, for a man to sell his own children to human flesh-mongers, . . . for, unless he does this, he must not only whip them himself, but must stand by and see one white son tie up his brother, of but few shades darker . . . and ply the gory lash to his naked back.

—Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Written by Himself (1845)

What moral complications did slavery unleash upon White enslavers in the South, according to Douglass? What imagery does he use?

The Fugitive Slave Act

The model of resistance to the slave power only became more pronounced after 1850, when the long-standing Fugitive Slave Act was given new teeth. Though a legal mandate to return runway enslaved persons had existed in U.S. federal law since 1793, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 upped the ante by harshly penalizing officials who failed to arrest runaways and private citizens who tried to help them. This law, coupled with growing concern over the possibility that slavery would be allowed in Kansas when it was admitted as a state, made the 1850s a highly volatile and violent period of American antislavery. Reform took a backseat as armed mobs protected runaway enslaved persons in the North and abolitionists engaged in bloody skirmishes in the West. Culminating in John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the violence of the 1850s convinced many Americans that the issue of slavery was pushing the nation to the brink of sectional cataclysm. After two decades of immediatist agitation, the idealism of revivalist perfectionism had given way to a protracted battle for the moral soul of the country.

John Brown at harper’s ferry

In 1859, White abolitionist John Brown led an armed raid on the federal armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Brown had been involved in several other violent anti-slavery events in Kansas before organizing the raid on Harper’s Ferry. His goal was to trigger a nationwide uprising by providing enslaved Virginians with weapons to fight for their freedom. Prior to the raid, Brown prepared a new Constitution which he hoped would replace the original and explicitly outlaw slavery in the U.S. Brown worked frequently with Harriett Tubman, whom he referred to as “General Tubman,” and she helped him to recruit men for his missions.

On October 16th, Brown took 18 men and attacked the armory at Harper’s Ferry. Local militiamen surrounded the raiders and waited on military reinforcements, which came from a company of U.S. Marines and soldiers commanded by Robert E. Lee. Brown and his men killed four of their opponents but lost ten of their own men. The trial for the captured leaders of the raid was national news, stoking fears of more armed rebellions in the South and inflaming tensions between the South and the North even further. Brown and four of his compatriots were convicted and hanged in December 1859.

For all of the problems that abolitionism faced, the movement was far from a failure. The prominence of African Americans in abolitionist organizations offered a powerful, if imperfect, model of interracial coexistence. While immediatists always remained a minority, their efforts paved the way for the moderately antislavery Republican Party to gain traction in the years preceding the Civil War. It is hard to imagine that Abraham Lincoln could have become president in 1860 without the ground prepared by antislavery advocates and without the presence of radical abolitionists against whom he could be cast as a moderate alternative. Though it ultimately took a civil war to break the bonds of slavery in the United States, the evangelical moral compass of revivalist Protestantism provided motivation for the embattled abolitionists.

Try It

Glossary

abolitionist: a believer in the complete elimination of slavery

immediatism: the moral demand to take immediate action against slavery to bring about its complete end, not gradually and not conditional

Frederick Douglass: a formerly enslaved man who escaped and became a prominent antislavery speaker and writer; his memoirs of his time in captivity were published by William Lloyd Garrison and widely disseminated as part of Garrison’s campaign of moral suasion to end slavery

Fugitive Slave Act: originally passed in the 18th century to require escaped enslaved persons to be returned to their captors, in the 19th century the law was updated to include punishment for any person found to be harboring or assisting fugitive enslaved persons

gag rule: a rule passed in Congress in the mid-19th-century which disallowed the reading of antislavery petitions in the House of Representatives

Liberty Party: a more moderate antislavery party that supported gradual emancipation, nonviolent and nonradical tactics, and did not allow women to take leadership positions

moral suasion: an abolitionist technique of appealing to the consciences of the public, especially enslavers

Candela Citations

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/13-4-addressing-slavery. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Antislavery and Abolitionism. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/10-religion-and-reform/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Unidentified Artist - Frederick Douglass - Google Art Project-restore. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Unidentified_Artist_-_Frederick_Douglass_-_Google_Art_Project-restore.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright