Learning Objectives

- Describe Jackson’s rise to the presidency and the election of 1828

- Explain the early scandals during Andrew Jackson’s first term in office

A turning point in American political history occurred in 1828, which witnessed the election of Andrew Jackson over the incumbent John Quincy Adams. While democratic practices had been in ascendance since 1800, the year also saw the further expansion of a democratic spirit in the United States. Supporters of Jackson called themselves Democrats or the Democracy, giving birth to the Democratic Party. Political authority appeared to rest with the majority as never before.

Andrew Jackson’s Rise to the PResidency

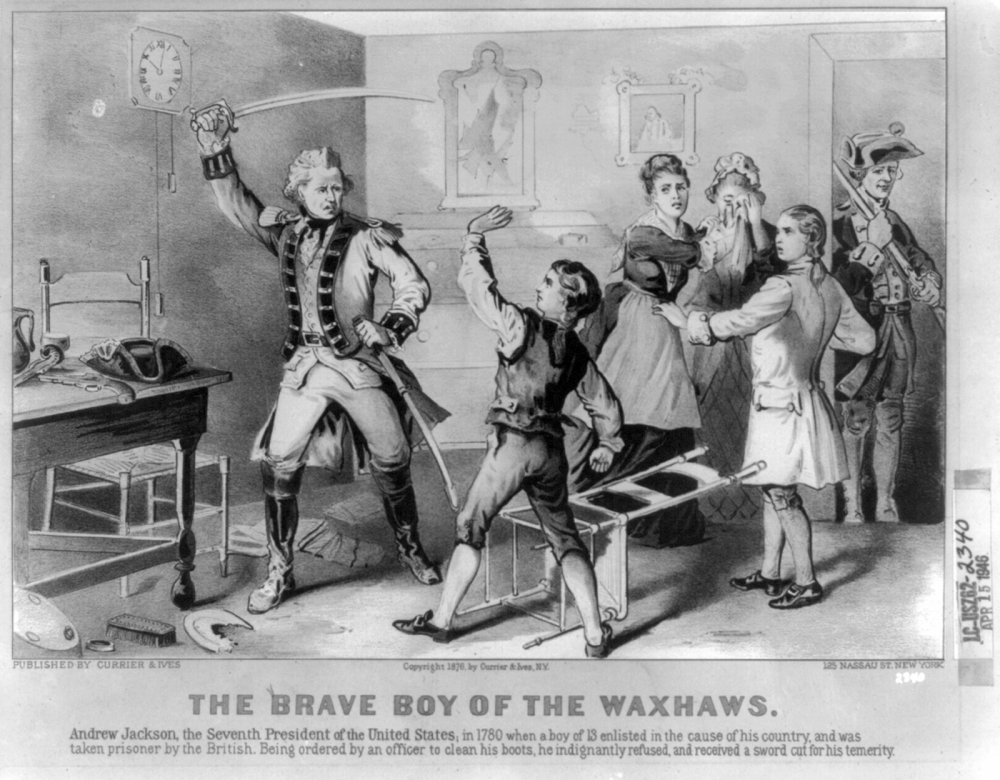

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, on the border between North and South Carolina, to two immigrants from northern Ireland. He grew up during dangerous times. At age thirteen, he joined an American militia unit in the Revolutionary War. He was soon captured, and a British officer slashed at his head with a sword after he refused to shine the officer’s shoes. Disease during the war had claimed the lives of his two brothers and his mother, leaving him an orphan. Their deaths and his wounds had left Jackson with a deep and abiding hatred of Great Britain.

After the war, Jackson moved west to frontier Tennessee, where despite his poor education, he prospered, working as a lawyer and acquiring land and enslaved laborers. (He would eventually come to keep 150 enslaved people at the Hermitage, his plantation near Nashville.) In 1796, Jackson was elected as a U.S. representative, and a year later he won a seat in the Senate, although he resigned within a year, citing financial difficulties.

Thanks to his political connections, Jackson obtained a general’s commission at the outbreak of the War of 1812. Despite having no combat experience, General Jackson quickly impressed his troops, who nicknamed him “Old Hickory” after a particularly tough kind of tree.

Jackson led his militiamen into battle in the Southeast, first during the Creek War, a side conflict that started between different factions of Muskogee (Creek) fighters in present-day Alabama. In that war, he won a decisive victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. A year later, he also defeated a large British invasion force at the Battle of New Orleans. There, Jackson’s troops—including backwoods militiamen, free Blacks, Native Americans, and a company of slave-trading pirates—successfully defended the city and inflicted more than two thousand casualties against the British, sustaining barely three hundred casualties of their own. The Battle of New Orleans was a thrilling victory for the United States, but it actually happened several days after a peace treaty was signed in Europe to end the war. News of the treaty had not yet reached New Orleans.

The end of the War of 1812 did not end Jackson’s military career. In 1818, as commander of the U.S. southern military district, Jackson also launched an invasion of Spanish-owned Florida. He was acting on vague orders from the War Department to break the resistance of the region’s Seminole people, who protected runaway enslaved people and attacked American settlers across the border. On Jackson’s orders in 1816, U.S. soldiers and their Creek allies had already destroyed the “Negro Fort,” a British-built fortress on Spanish soil, killing 270 formerly enslaved people and executing some survivors. In 1818, Jackson’s troops crossed the border again. They occupied Pensacola, the main Spanish town in the region, and arrested two British subjects, whom Jackson executed for helping the Seminoles. The execution of these two Britons created an international diplomatic crisis.

Figure 1. Images like this one—showing Jackson refusing to bow to the whims of a British officer and defending his family—helped establish the memory of Jackson as the keeper of the Revolution and a leader of the common man.

Most officials in President James Monroe’s administration called for Jackson’s censure. But Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the son of former president John Adams, found Jackson’s behavior useful. He defended the impulsive general, arguing that he had been forced to act. Adams used Jackson’s military successes in this First Seminole War to persuade Spain to accept the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, which gave Florida to the United States.

Any friendliness between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, however, did not survive long. In 1824, four nominees competed for the presidency in one of the closest elections in American history. Each came from a different part of the country—Adams from Massachusetts, Jackson from Tennessee, William H. Crawford from Georgia, and Henry Clay from Kentucky. Jackson won more popular votes than anyone else. But with no majority winner in the Electoral College, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives. There, Adams used his political clout to claim the presidency, persuading Clay to support him. Jackson would never forgive Adams, whom his supporters accused of engineering a “corrupt bargain” with Clay to circumvent the popular will. Jackson used this anger to fuel his campaign against Adams in the 1828 election.

Visit The Hermitage to explore a timeline of Andrew Jackson’s life and career. How do you think the events of his younger life affected the trajectory of his political career?

The Campaign and Election of 1828

Figure 2. The bitter rivalry between Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay was exacerbated by the “corrupt bargain” of 1824, which Jackson made much of during his successful presidential campaign in 1828. This drawing, published in the 1830s during the debates over the future of the Second Bank of the United States, shows Clay sewing up Jackson’s mouth while the “cure for calumny [slander]” protrudes from his pocket.

During the 1800s, democratic reforms made steady progress with the abolition of property qualifications for voting and the birth of new forms of political party organization. The 1828 campaign pushed new democratic practices even further and highlighted the difference between the Jacksonian expanded electorate and the older, more exclusive Adams style. A slogan of the day, “Adams who can write/Jackson who can fight,” captured the contrast between Adams the aristocrat and Jackson the frontiersman.

The 1828 campaign differed significantly from earlier presidential contests because of the party organization that promoted Andrew Jackson. Jackson and his supporters reminded voters of the “corrupt bargain” of 1824. They framed it as the work of a small group of political elites deciding who would lead the nation, acting in a self-serving manner and ignoring the will of the majority. From Nashville, Tennessee, the Jackson campaign organized supporters around the nation through editorials in partisan newspapers and other publications. Pro-Jackson newspapers heralded the “hero of New Orleans” while denouncing Adams. Though he did not wage an election campaign filled with public appearances, Jackson did give one major campaign speech in New Orleans on January 8, the anniversary of the defeat of the British in 1815. He also engaged in rounds of discussion with politicians who came to his home, the Hermitage, in Nashville.

At the local level, Jackson’s supporters worked to bring in as many new voters as possible. Rallies, parades, and other rituals further broadcast the message that Jackson stood for the common man against the corrupt elite backing Adams and Clay. Democratic organizations called Hickory Clubs, a tribute to Jackson’s nickname, Old Hickory, also worked tirelessly to ensure his election.

Pro-Jackson partisans accused Adams of elitism and claimed that while serving in Russia as a diplomat he had offered the Russian emperor an American prostitute. Adams’s supporters, on the other hand, accused Jackson of murder and attacked the morality of his marriage, pointing out that Jackson had unwittingly married his wife Rachel before the divorce ending her prior marriage was complete. (Rachel Jackson died suddenly before his inauguration and Jackson would never forgive the people who attacked his wife’s character during the campaign.)

In November 1828, Jackson won an overwhelming victory over Adams, capturing 56 percent of the popular vote and 68 percent of the electoral vote. As in 1800, when Jefferson had won over the Federalist incumbent John Adams, the presidency passed to a new political party, the Democrats. The election was the climax of several decades of expanding democracy in the United States and the end of the older politics of deference.

Scandal in the Presidency

Amid revelations of widespread fraud, including the disclosure that some $300,000 was missing from the Treasury Department, Jackson removed almost 50 percent of appointed civil officers, which allowed him to handpick their replacements. This replacement of appointed federal officials is called rotation in office. Lucrative posts, such as postmaster and deputy postmaster, went to party loyalists, especially in places where Jackson’s support had been weakest, such as New England. Some Democratic newspaper editors who had supported Jackson during the campaign also gained public jobs.

Jackson’s opponents were angered and took to calling the practice a new example of the spoils system, after the policies of Van Buren’s Bucktail Republican Party. The rewarding of party loyalists with government jobs resulted in spectacular instances of corruption. Perhaps the most notorious occurred in New York City, where a Jackson appointee made off with over $1 million. Such examples seemed proof positive that the Democrats were disregarding merit, education, and respectability in decisions about the governing of the nation.

Figure 3. Peggy O’Neal was so well known that advertisers used her image to sell products to the public. In this anonymous nineteenth-century cigar-box lid, her portrait is flanked by vignettes showing her scandalous past. On the left, President Andrew Jackson presents her with flowers. On the right, two men fight a duel for her.

In addition to dealing with rancor over rotation in office, the Jackson administration became embroiled in a personal scandal known as the Petticoat Affair. This incident exacerbated the division between the president’s team and the insider class in the nation’s capital, who found the new arrivals from Tennessee lacking in decorum and propriety. At the center of the storm was Margaret (“Peggy”) O’Neal, a well-known socialite in Washington, DC.

Although women could not vote or hold office, they played an important role in politics as people who controlled influence. They helped hold official Washington together. And according to one local society woman, “the ladies” had “as much rivalship and party spirit, desire of precedence and authority” as male politicians had.[1] These women upheld a strict code of femininity and sexual morality. They paid careful attention to the rules that governed personal interactions and official relationships.

Peggy O’Neal had connections to the republic’s most powerful men. She married John Timberlake, a naval officer, and they had three children. Rumors abounded, however, about her involvement with John Eaton, a U.S. senator from Tennessee who had come to Washington in 1818.

Timberlake committed suicide in 1828, setting off a flurry of rumors that he had been distraught over his wife’s reputed infidelities. Eaton and Mrs. Timberlake married soon after, with the full approval of President Jackson. The so-called Petticoat affair divided Washington society. Many Washington socialites snubbed the new Mrs. Eaton as a woman of low moral character. Among those who would have nothing to do with her was Vice President John C. Calhoun’s wife, Floride. Calhoun fell out of favor with President Jackson, who defended Peggy Eaton and derided those who would not socialize with her, declaring she was “as chaste as a virgin.” (Jackson had personal reasons for defending Eaton: he drew a parallel between Eaton’s treatment and that of his late wife, Rachel.) Martin Van Buren, who defended the Eatons and organized social gatherings with them, became close to Jackson, who came to rely on a group of informal advisers that included Van Buren and was dubbed the Kitchen Cabinet. This select group of presidential supporters highlights the importance of party loyalty to Jackson and the Democratic Party.

In one of the most famous presidential meetings in American history, Jackson called together his cabinet members to discuss what they saw as the bedrock of society: women’s position as protectors of the nation’s values. There, the men of the cabinet debated Margaret Eaton’s character. Jackson delivered a long defense, methodically presenting evidence against her attackers. But the men attending the meeting—and their wives—were not swayed. They continued to shun Margaret Eaton, and the scandal was resolved only with the resignation of four members of the cabinet, including Eaton’s husband.

Try It

Watch it

In this video, you’ll learn about President Jackson and the ways in which he transformed the office of the presidency (for better or for worse).

You can view the transcript for “Age of Jackson: Crash Course US History #14” here (opens in new window).

Review Questions

1. What were the planks of Andrew Jackson’s campaign platform in 1828?

2. What was the significance of the Petticoat affair?

Glossary

Kitchen Cabinet: a nickname for Andrew Jackson’s informal group of loyal advisers

Petticoat affair: a romantic scandal that highlighted the divisions between Andrew Jackson’s circle and the established socialites of Washington, D.C.

rotation in office: originally, simply the system of having term limits on political appointments; in the Jackson era, this came to mean the replacement of officials with party loyalists

- Margaret Bayard Smith to Margaret Bayard Boyd, December 20 [?], 1828, Margaret Bayard Smith Papers, quoted in Elizabeth R. Varon, We Mean to Be Counted: White Women and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 215. ↵