Learning Objectives

- Explain the “Bank War” and its political significance

The Bank War

Andrew Jackson’s first term was full of controversy. For all of his reputation as a military and political warrior, however, the most characteristic struggle of his presidency was financial. In his second term, he waged a “war” against the Bank of the United States.

Congress established the Bank of the United States in 1791 as a key pillar of Alexander Hamilton’s financial program, but its twenty-year charter expired in 1811. Congress, swayed by the majority’s hostility to the bank as an institution catering to the wealthy elite, did not renew the charter at that time. In its place, Congress approved a new national bank—the Second Bank of the United States—in 1816. It too had a twenty-year charter, set to expire in 1836.

The Second Bank of the United States was created to stabilize the banking system. More than two hundred banks existed in the United States in 1816, and almost all of them issued paper money. In other words, citizens faced a bewildering welter of paper money with no standard value. In fact, the problem of paper money had contributed significantly to the Panic of 1819.

In the 1820s, the national bank moved into a magnificent new building in Philadelphia. However, despite Congress’s approval of the Second Bank of the United States, a great many people continued to view it as tool of the wealthy, an anti-democratic force. President Jackson was among them; he had faced economic crises of his own during his days speculating in land, an experience that had made him uneasy about paper money. To Jackson, hard currency—that is, gold or silver—was the far better alternative. The president also personally disliked the bank’s director, Nicholas Biddle.

An astute reader of public sentiment, Jackson used the debate over a centralized bank to promote his own view of presidential powers. Departing from the idea that Congress represented the will of the people, the president maintained that he was the symbolic representation of the electorate. In keeping with this conviction, Jackson made his case regarding the dangerous power of the bankers directly to the people, effectively bypassing Congress. While he may have read the public mood more accurately than his Whig adversaries, his sweeping decentralization of America’s banking system ultimately led to state banks issuing far too much paper currency. With prices rising and real incomes falling, the speculative balloon eventually deflated and harmed the very “farmers, mechanics, and laborers” that Jackson claimed to be championing.[1]

A large part of the allure of mass democracy for politicians was the opportunity to capture the anger and resentment of ordinary Americans against what they saw as the privileges of a few. One of the leading opponents of the bank was Thomas Hart Benton, a senator from Missouri, who declared that the bank served “to make the rich richer, and the poor poorer.” Also, The self-important statements of director Biddle, who claimed to have more power than President Jackson, helped fuel sentiments like Benton’s.

Jackson Vetos the Bank

In the reelection campaign of 1832, Jackson’s opponents in Congress, including Henry Clay, hoped to use their support of the bank to their advantage. In January 1832, they pushed for legislation that would recharter it, even though its charter was not scheduled to expire until 1836. When the bill for rechartering passed and came to President Jackson, he used his executive authority to veto the measure.

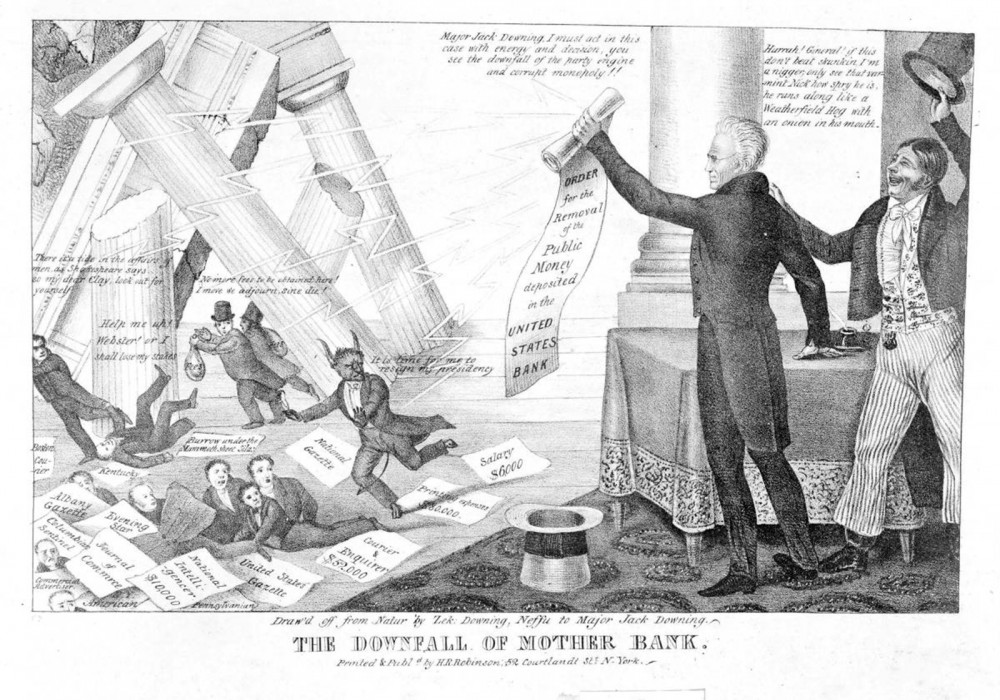

Figure 1. “The bank,” Andrew Jackson told Martin Van Buren, “is trying to kill me, but I will kill it!” That is just the unwavering force that Edward Clay depicted in this lithograph, which praised Jackson for terminating the Second Bank of the United States. Clay shows Nicholas Biddle as the Devil running away from Jackson as the bank collapses around him, his hirelings, and speculators.

In his veto message, Jackson called the bank unconstitutional and “dangerous to the liberties of the people.” The charter, he explained, didn’t do enough to protect the bank from its British stockholders, who might not have Americans’ interests at heart. In addition, Jackson wrote, the Bank of the United States was virtually a federal agency, but it had powers that were not granted anywhere in the Constitution. Worst of all, the bank was a way for well-connected people to get richer at everyone else’s expense. “The rich and powerful,” the president declared, “too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.”[2] Only a strictly limited government, Jackson believed, would treat people equally.

Figure 2. In General Jackson Slaying the Many Headed Monster (1836), the artist, Henry R. Robinson, depicts President Jackson using a cane marked “Veto” to battle a many-headed snake representing state banks, which supported the national bank. Battling alongside Martin Van Buren and Jack Downing, Jackson addresses the largest head, that of Nicholas Biddle, the director of the national bank: “Biddle thou Monster Avaunt [go away]!! . . .”

The defeat of the Second Bank of the United States demonstrates Jackson’s ability to focus on the specific issues that aroused the democratic majority. Jackson understood people’s anger and distrust toward the bank, which stood as an emblem of special privilege and top-down government. He skillfully used that perception to his advantage, presenting the bank issue as a struggle of ordinary people against a rapacious elite class who cared nothing for the public and pursued only their own selfish ends. As Jackson portrayed it, his was a battle for small government and ordinary Americans. His stand against what bank opponents called the monster bank proved very popular, and the Democratic press lionized him for it. In the election of 1832, Jackson received nearly 53 percent of the popular vote against his opponent Henry Clay.

Watch It

Watch the video below to better understand Andrew Jackson’s rationale for opposing a centralized bank. How do the historians’ accounts shed light on Jackson’s political priorities and sympathies? What did he think was at stake if private finance operated a putatively “public” national bank?

You can view the transcript for “The War Against the Bank” here (opens in new window).

Figure 3. In 1835, Jackson became the first US President on whom an assassination attempt was carried out. While unsuccessful, it became another moment for Jackson to establish his persona as impulsive and passionate when, after the assassin’s gun misfired twice, Jackson beat the man senseless with a cane.

Jackson’s veto was only one part of the war on the “monster bank.” In 1833, the president removed the deposits from the national bank and placed them in state banks. Biddle, the bank’s director, retaliated by restricting loans to the state banks, resulting in a reduction of the money supply. The financial turmoil only increased when Jackson issued an executive order known as the Specie Circular, which required that western land sales be conducted using gold or silver only (specie is the term for money in the form of coins rather than paper). Unfortunately, this policy proved a disaster when the Bank of England, the source of much of the hard currency borrowed by American businesses, dramatically cut back on loans to the United States. Without the flow of hard currency from England, American depositors drained the gold and silver from their own domestic banks, making hard currency scarce. Adding to the economic distress of the late 1830s, cotton prices plummeted, contributing to a financial crisis called the Panic of 1837. This economic panic would prove politically useful for Jackson’s opponents in the coming years and Van Buren, elected president in 1836, would pay the price for Jackson’s hard-currency preferences.

Understanding Speculation and the Bank Crisis

Link to learning

Explore a Library of Congress collection of 1830s political cartoons from the pages of Harper’s Weekly to learn more about how Andrew Jackson was viewed by the public in that era.

Try It

Review Question

Why did the Second Bank of the United States make such an inviting target for President Jackson?

Glossary

monster bank: the term Democratic opponents used to denounce the Second Bank of the United States as an emblem of special privilege and top-down government

Specie Circular: Jackson’s executive order requiring that western land sales be transacted using gold or silver instead of paper notes

- Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty: an American History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2011) 401-403. ↵

- Andrew Jackson, veto message regarding the Bank of the United States, July 10, 1832, Avalon Project, Yale Law School. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/ajveto01.asp. ↵