Learning Objectives

- Explain the labor-intensive processes of cotton production

- Describe the impact of cotton on the economy of the South

Figure 1. Major events related to the rise of the “Cotton Kingdon” and a Southern society dependent on enslaved laborers.

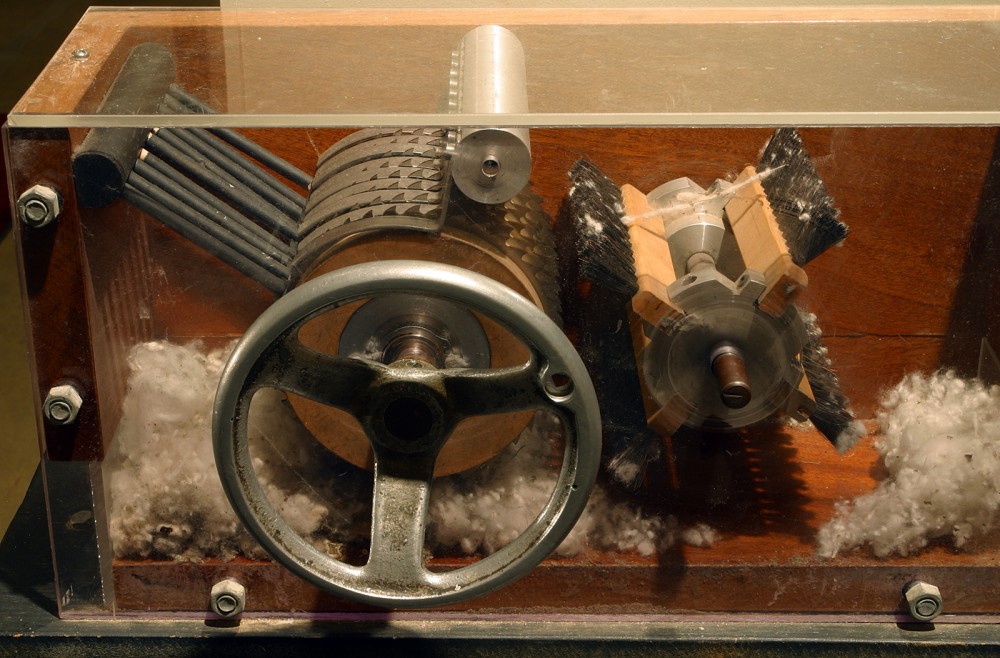

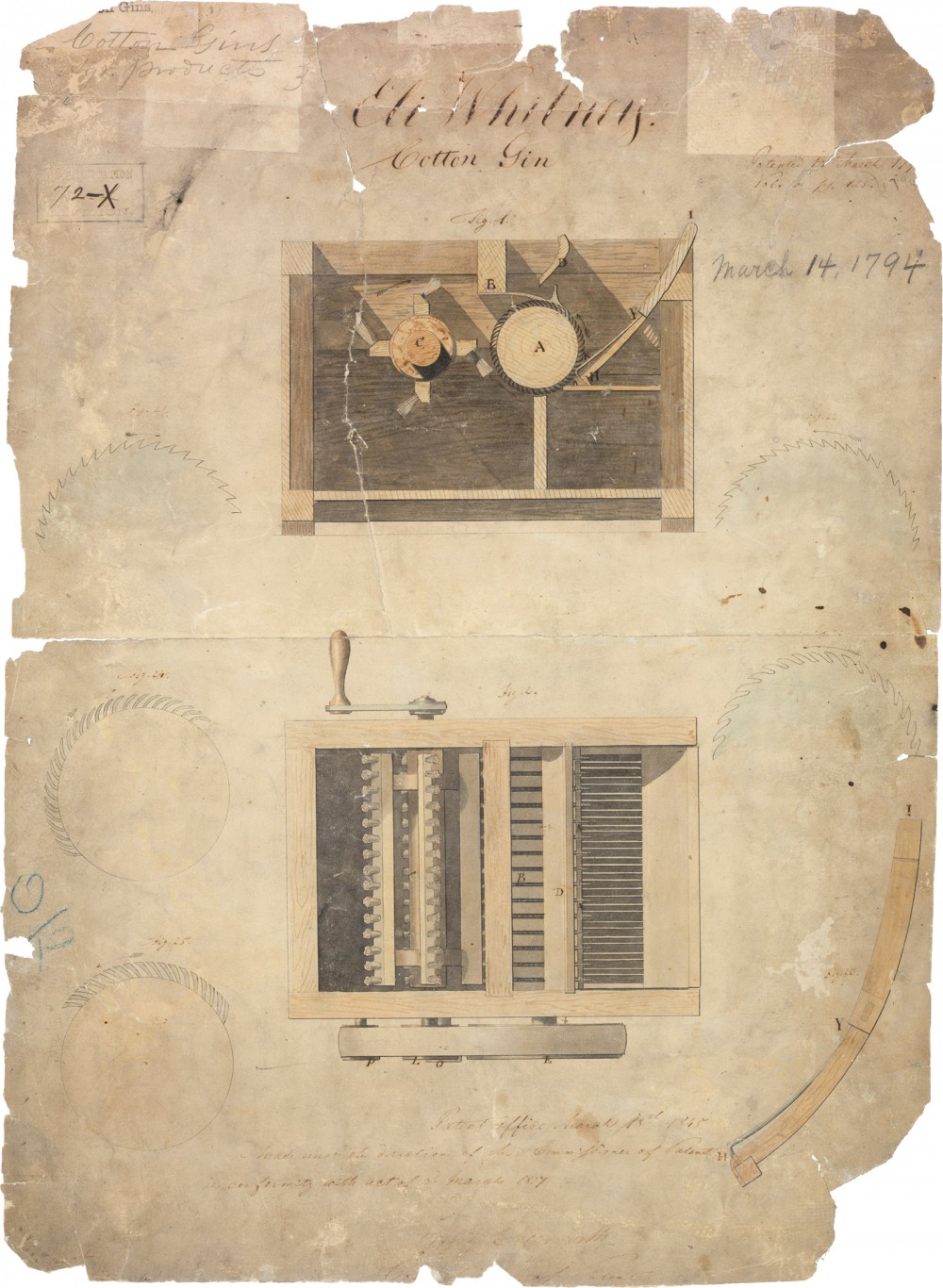

In the antebellum era—that is, in the years before the Civil War—American planters in the South continued to grow Chesapeake tobacco and Carolina rice as they had in the colonial era. Cotton, however, emerged as the antebellum South’s major commercial crop, eclipsing tobacco, rice, and sugar in economic importance. By 1860, the region was producing two-thirds of the world’s cotton. In 1793, Eli Whitney revolutionized the production of cotton when he invented the cotton gin, a device that separated the seeds from raw cotton. Suddenly, a process that was extraordinarily labor-intensive when done by hand could be completed quickly and easily. American plantation owners, who were searching for a successful staple crop to compete on the world market, found it in cotton.

As a commodity, cotton had the advantage of being easily stored and transported. A demand for it already existed in the industrial textile mills in Great Britain, and in time a steady stream of American cotton produced by enslaved labor would also supply northern textile mills. Southern cotton, picked and processed by American enslaved persons, helped fuel the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution in both the United States and Great Britain.

King Cotton

Figure 2. Eli Whitney’s mechanical cotton gin revolutionized cotton production and expanded and strengthened slavery throughout the South. Eli Whitney’s Patent for the Cotton gin, March 14, 1794; Records of the Patent and Trademark Office; Record Group 241.

Almost no cotton was grown in the United States in 1787, the year the federal constitution was written. However, following the War of 1812, a huge increase in production resulted in the so-called cotton boom, and by midcentury, cotton became the key cash crop (a crop grown to sell rather than for the farmer’s sole use) of the southern economy and the most important American commodity. By 1850, of the 3.2 million enslaved people in the country’s fifteen slave states, 1.8 million were producing cotton; by 1860, enslaved labor was producing over two billion pounds of cotton per year. Indeed, American cotton soon made up two-thirds of the global supply, and production continued to soar. By the time of the Civil War, South Carolina politician James Hammond confidently proclaimed that the North could never threaten the South because “cotton is king.”

Petit Gulf, the type of cotton grown in the South, was said to slide through the cotton gin more easily than any other strain. It also grew tightly, producing more usable cotton than anyone had imagined to that point. This discovery came at a time when Native peoples were removed from the Southwest—southern Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and northern Louisiana. Following the displacement of Indigenous peoples, land became readily available for White men with a few dollars and big dreams. This system, enacted through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, allowed the federal government to survey, divide, and auction off millions of acres of land for however much bidders were willing to pay. Suddenly, farmers with aspirations of owning a large plantation could purchase dozens, even hundreds, of acres in the fertile Mississippi River Delta for cents on the dollar. Pieces of land that would cost thousands of dollars elsewhere sold in the 1830s for several hundred, at prices as low as 40¢ per acre.

Petit Gulf dominated cotton production in the Mississippi River Valley—home of the new slave states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri—as well as in other states like Texas. Whenever new slave states entered the Union, White slaveholders sent armies of the enslaved to clear the land in order to grow and pick the lucrative crop. The phrase “to be sold down the river,” used by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, refers to this forced migration from the upper southern states to the Deep South, lower on the Mississippi, to grow cotton.

Uncle Tom’s cabin

Written in 1852 by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin tells the story of Uncle Tom, an enslaved person, living on a plantation in the South. The novel depicts the reality of life for many enslaved persons. Uncle Tom’s Cabin is credited with stoking the growing abolitionist movement in the 1850s because it brought enslaved persons’ lives into sharp focus for the first time. More than any other novel of the time, it had a profound impact on attitudes towards slavery and African Americans in the U.S. It was the best-selling novel and the second best-selling book of the 19th century, following the Bible. The novel was also made into a number of plays that further spread the story.

However, in more recent years the novel has been criticized for popularizing negative stereotypes about African Americans. While Uncle Tom is kind and loving to his fellow enslaved persons, he is also dutiful and subservient to his White master and mistress. Another stereotype is that of the caring “mammy” figure taking care of the White children. These depictions helped solidify stereotypes of African Americans.

Producing Cotton

The enslaved people who built this cotton kingdom in the South with their forced labor started by clearing the land. Although the Jeffersonian vision of the settlement of new U.S. territories entailed White yeoman farmers single-handedly carving out small independent farms, the reality proved quite different. Entire old-growth forests and cypress swamps fell to the axe as enslaved people were ordered to strip the vegetation to make way for cotton. With the land cleared, they readied the earth by plowing and planting. To ambitious White planters, the extent of new land available for cotton production seemed almost limitless, and many planters simply leapfrogged from one area to the next, abandoning their fields every ten to fifteen years after the soil became exhausted. As a result, enslaved people composed the vanguard of this American expansion to the West.

Figure 4. In the late nineteenth century, J. N. Wilson captured this image of harvest time at a southern plantation. While the workers in this photograph are not enslaved laborers, the process of cotton harvesting shown here had changed little from antebellum times.

Cotton planting took place in March and April, when enslaved people planted seeds in rows around three to five feet apart. Over the next several months, from April to August, they carefully tended the plants. Weeding the cotton rows took significant energy and time. In August, after the cotton plants had flowered and the flowers had begun to give way to cotton bolls (the seed-bearing capsule that contains the cotton fiber), all the plantation’s enslaved men, women, and children worked together to pick the crop. On each day of cotton picking, enslaved workers went to the fields with sacks, which they would fill as many times as they could. The effort was laborious, and a White “driver” employed the lash to make the enslaved people work as quickly as possible.

Cotton planters projected the amount of cotton they could harvest based on the number of enslaved people under their control. In general, planters expected a good “hand,” or enslaved laborer, to work ten acres of land and pick two hundred pounds of cotton a day. An overseer or “master” measured each enslaved individual’s daily yield. Great pressure existed to meet the expected daily amount, and some overseers whipped enslaved people who picked less than expected.

Cotton picking occurred as many as seven times a season as the plant grew and continued to produce bolls through the fall and early winter. During the picking season, enslaved people worked from sunrise to sunset with a ten-minute break at lunch; many enslavers tended to give them little to eat, since spending on food would cut into their profits. Other enslavers knew that feeding the enslaved could increase productivity and therefore provided what they thought would help ensure a profitable crop. Enslaved people’s day didn’t end after they picked the cotton; once they had brought it to the gin house to be weighed, they then had to care for the animals and perform other chores. Indeed, they often maintained their own gardens and livestock, which they tended after working the cotton fields, in order to supplement their supply of food.

Sometimes the cotton was dried before it was ginned (put through the process of separating the seeds from the cotton fiber). The cotton gin allowed an enslaved laborer to remove the seeds from fifty pounds of cotton a day, compared to one pound if done by hand. After the seeds had been removed, the cotton was pressed into bales. These bales, weighing about four hundred to five hundred pounds, were wrapped in burlap cloth and sent down the Mississippi River.

Watch It

This video shows how cotton is produced and explains why the invention of the cotton gin transformed the history of the South.

You can view the transcript for “The cost of cotton production | Georgia Stories” here (opens in new window).

You can also visit the Internet Archive to watch a 1937 WPA film showing cotton bales being loaded onto a steamboat.

Try It

A Booming Economy

Thousands rushed into the Cotton Belt. Joseph Holt Ingraham, a writer and traveler from Maine, called it a “mania.”[1] William Henry Sparks, a lawyer living in Natchez, Mississippi, remembered it as “a new El Dorado” in which “fortunes were made in a day, without enterprise or work.” The change was astonishing. “Where yesterday the wilderness darkened over the land with her wild forests,” he recalled, “to-day the cotton plantations whitened the earth.”[2] Money flowed from banks, many newly formed, on promises of “other-worldly” profits and overnight returns. Banks in New York City, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and even London offered lines of credit to anyone looking to buy land in the Southwest. Some even sent their own agents to purchase cheap land at auction for the express purpose of selling it, sometimes the very next day, at double and triple the original value, a process known as speculation.

The numbers were staggering. In 1793, just a few years after the first, albeit unintentional, shipment of American cotton to Europe, the South produced around five million pounds of cotton, again almost exclusively the product of South Carolina’s Sea Islands. Seven years later, in 1800, South Carolina remained the primary cotton producer in the South, sending 6.5 million pounds of the luxurious long-staple blend to markets in Charleston, Liverpool, London, and New York. But as the tighter, more abundant, and vibrant Petit Gulf strain moved west with the dreamers, schemers, and speculators, the American South quickly became the world’s leading cotton producer. By 1835, the five main cotton-growing states—South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—produced more than five hundred million pounds of Petit Gulf for a global market stretching from New Orleans to New York and to London, Liverpool, Paris, and beyond. That five hundred million pounds of cotton made up nearly 55 percent of the entire United States export market, a trend that continued nearly every year until the outbreak of the Civil War. Indeed, the two billion pounds of cotton produced in 1860 alone amounted to more than 60 percent of the United States’ total exports for that year.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about the Cotton Revolution from Crash Course Black American History to learn about the demand for cotton and the resulting expansion of slavery.

The Rise of Southern Cities

Much of the story of slavery and cotton lies in the rural areas where cotton actually grew. Enslaved laborers worked in the fields, and planters and farmers held reign over their plantations and farms. But the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s saw an extraordinary spike in urban growth across the South. For nearly a half-century after the Revolution, the South existed as a series of plantations, county seats, and small towns, some connected by roads, others connected only by rivers, streams, and lakes. Cities certainly existed, but they served more as local ports than as regional, or national, commercial hubs. For example, New Orleans, then the capital of Louisiana, which entered the union in 1812, was home to just over 27,000 people in 1820; and even with such a seemingly small population, it was the second-largest city in the South—Baltimore had more than 62,000 people in 1820. Given the standard nineteenth-century measurement of an urban space (2,500+ people), the South had just ten in that year, one of which—Mobile, Alabama—contained only 2,672 individuals, nearly half of whom were enslaved.

As late as the 1820s, southern life was predicated on a rural lifestyle—farming, laboring, acquiring land and enslaved laborers, and producing whatever that land and those enslaved laborers could produce. The market, often located in the nearest town or city, rarely stretched beyond state lines. Even in places like New Orleans, Charleston, and Norfolk, Virginia, which had active ports as early as the 1790s, shipments rarely, with some notable exceptions, left American waters or traveled farther than the closest port down the coast. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, American involvement in international trade was largely confined to ports in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and sometimes Baltimore—which loosely falls under the demographic category of the South. Imports dwarfed exports. In 1807, U.S. imports outnumbered exports by nearly $100 million, and even as the Napoleonic Wars broke out in Europe, causing a drastic decrease in European production and trade, the United States still took in almost $50 million more than it sent out.

Cotton changed much of this, at least with respect to the South. Before cotton, the South had few major ports, almost none of which actively maintained international trade routes or even domestic supply routes. Internal travel and supply was difficult, especially on the waters of the Mississippi River, the main artery of the North American continent, and the eventual gold mine of the South. With the Mississippi’s strong current, deadly undertow, and constant sharp turns, sandbars, and subsystems, navigation was difficult and dangerous. The river promised a revolution in trade, transportation, and commerce only if the technology existed to handle its impossible bends and fight against its southbound current. By the 1820s and into the 1830s, small ships could successfully navigate their way to New Orleans from as far north as Memphis and even St. Louis, if they so dared. But the problem was getting back. Most often, traders and sailors scuttled their boats on landing in New Orleans, selling the wood for a quick profit or a journey home on a wagon or caravan.

Figure 5. New Orleans in 1852 shows the massive growth of the city, partially brought about by the proliferation of steamboats and the cotton boom in the South.

The rise of cotton benefited from a change in transportation technology that aided and guided the growth of southern cotton into one of the world’s leading commodities. In January 1812, a 371-ton ship called the New Orleans arrived at its namesake city from the distant internal port of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This was the first steamboat to navigate the internal waterways of the North American continent from one end to the other and remain capable of returning home. The technology was far from perfect—the New Orleans sank two years later after hitting a submerged sandbar covered in driftwood—but its successful trial promised a bright, new future for river-based travel.

Investors poured huge sums into steamships. In 1817, only seventeen plied the waters of western rivers, but by 1837, there were over seven hundred steamships in operation. Major new ports developed at St. Louis, Missouri; Memphis, Tennessee; and other locations. By 1860, some thirty-five hundred vessels were steaming in and out of New Orleans, carrying an annual cargo made up primarily of cotton that amounted to $220 million worth of goods (approximately $7 billion in 2021 dollars). Steamboats, a crucial part of the transportation revolution thanks to their enormous freight-carrying capacity and ability to navigate shallow waterways, became a defining component of the cotton kingdom. Steamboats also illustrated the class and social distinctions of the antebellum age. While the decks carried precious cargo, ornate rooms graced the interior. In these spaces, Whites socialized in the ship’s saloons and dining halls while enslaved Black people served them

Figure 6. As in this depiction of the saloon of the Mississippi River steamboat Princess, elegant and luxurious rooms often occupied the interiors of antebellum steamships, whose decks were filled with cargo.

Coastal ports like New Orleans, Charleston, Norfolk, and even Richmond became targets of steamboats and coastal carriers. Merchants, traders, skilled laborers, and foreign speculators and agents flooded the towns. In fact, the South experienced a greater rate of urbanization between 1820 and 1860 than the seemingly more industrial, urban-based North. Urbanization of the South simply looked different from that seen in the North and in Europe. Where most northern and some European cities (most notably London, Liverpool, Manchester, and Paris) developed along the lines of industry, creating public spaces to boost the morale of wage laborers in factories, on the docks, and in storehouses, southern cities developed within the cyclical logic of sustaining the trade in cotton that justified and paid for the maintenance of an enslaved labor force. The growth of southern cities, then, allowed slavery to flourish and brought the South into a more modern world.

Between 1820 and 1860, quite a few southern towns experienced dramatic population growth, which paralleled the increase in cotton production and international trade to and from the South. The 27,176 people New Orleans claimed in 1820 expanded to more than 168,000 by 1860. In fact, in New Orleans, the population nearly quadrupled from 1830 to 1840 as the Cotton Revolution hit full stride. At the same time, Charleston’s population nearly doubled, from 24,780 to 40,522; Richmond expanded threefold, growing from a town of 12,067 to a capital city of 37,910; and St. Louis experienced the largest increase of any city in the nation, expanding from a frontier town of 10,049 to a booming Mississippi River metropolis of 160,773.

New Orleans had been part of the French empire before the United States purchased it, along with the rest of the Louisiana Territory, in 1803. In the first half of the nineteenth century, it rose in prominence and importance largely because of the cotton boom, steam-powered river traffic, and its strategic position near the mouth of the Mississippi River. Steamboats moved down the river transporting cotton grown on plantations along the river and throughout the South to the port at New Orleans. From there, the bulk of American cotton went to Liverpool, England, where it was sold to British manufacturers who ran the cotton mills in Manchester and elsewhere. This lucrative international trade brought new wealth and new residents to the city. By 1840, New Orleans alone had 12 percent of the nation’s total banking capital, and visitors often commented on the great cultural diversity of the city. In 1835, Joseph Holt Ingraham wrote: “Truly does New-Orleans represent every other city and nation upon earth. I know of none where is congregated so great a variety of the human species.” Slaves, cotton, and the steamship transformed the city from a relatively isolated corner of North America in the eighteenth century to a thriving metropolis that rivaled New York in importance.

Figure 7. This print of The Levee – New Orleans (1884) shows the bustling port of New Orleans with bales of cotton waiting to be shipped. The sheer volume of cotton indicates its economic importance throughout the century.

The astronomical rise of American cotton production came at the cost of the South’s first staple crop—tobacco. Perfected in Virginia but grown and sold in nearly every southern territory and state, tobacco served as the South’s main economic commodity for more than a century. But tobacco was a rough crop. It treated the land poorly, draining the soil of nutrients. Tobacco fields did not last forever. In fact, fields rarely survived more than four or five cycles of growth, which left them dried and barren, incapable of growing much more than patches of grass. Of course, tobacco is and was an addictive substance, but because of its violent pattern of growth, farmers had to move around, purchasing new lands, developing new methods of production, and even creating new fields through deforestation and westward expansion. Tobacco, then, was expensive to produce—and not only because of the ubiquitous use of slave labor. It required massive, temporary fields, large numbers of laborers, and constant movement.

Cotton was different, and it arrived at a time best suited for its success. Petit Gulf cotton, in particular, grew relatively quickly on cheap, widely available land. With the invention of the cotton gin in 1794, and the emergence of steam power three decades later, cotton became the common person’s commodity, the product with which the United States could expand westward, producing and reproducing Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an idyllic republic of small farmers—a nation in control of its land, reaping the benefits of honest, free, and self-reliant work, a nation of families and farmers, expansion and settlement. But this all came at a violent cost. With the democratization of land ownership through Indian removal, federal auctions, readily available credit, and the seemingly universal dream of cotton’s immediate profit, one of the South’s lasting traditions became normalized and engrained. And by the 1860s, that very tradition, seen as the backbone of southern society and culture, would split the nation in two. The heyday of American slavery had arrived.

Try It

Glossary

antebellum: a term meaning “before the war” and used to describe the decades before the American Civil War began in 1861

cash crop: a crop grown to be sold for profit instead of consumption by the farmer’s family

cotton boom: the upswing in American cotton production during the nineteenth century

cotton gin: a device, patented by Eli Whitney in 1794, that separated the seeds from raw cotton quickly and easily

Candela Citations

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/12-1-the-economics-of-cotton. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- The Importance of Cotton. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/11-the-cotton-revolution/#footnote_3_84. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Uncle Tom's Cabin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncle_Tom%27s_Cabin. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The cost of cotton production | Georgia Stories. Provided by: GPB Education. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIrC39WghF0. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Patent for Cotton Gin (1794). Authored by: Eli Whitney. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Patent_for_Cotton_Gin_%281794%29_-_hi_res.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cotton gin EWM 2007. Authored by: Tom Murphy VII. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cotton_gin_EWM_2007.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright