Learning Objectives

- Explain the purpose of the 1765 Stamp Act

- Describe the colonial responses to the Stamp Act

Figure 1. Events leading to the Revolutionary War (credit “1765”: modification of work by the United Kingdom Government)

The Stamp Act of 1765

Prime Minister Grenville, author of the Sugar Act of 1764, introduced the Stamp Act in the early spring of 1765. Under this act, anyone who used or purchased anything printed on paper had to buy a revenue stamp for it. In the same year, Parliament also passed the Quartering Act, a law that attempted to solve the problems of stationing troops in North America by requiring the colonies to provide barracks at their own cost. The British Parliament understood the Stamp Act and the Quartering Act as an assertion of their authority over colonial policy.

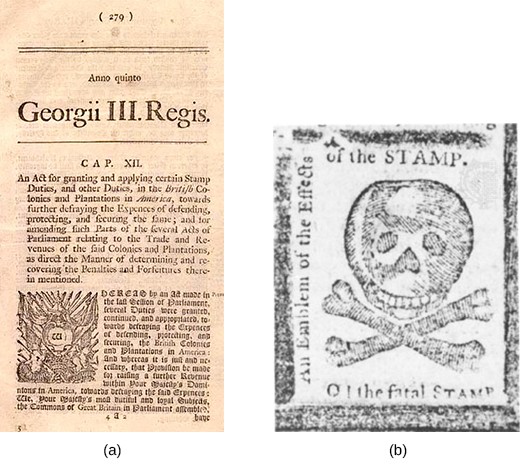

Figure 2. Under the Stamp Act, anyone who used or purchased anything printed on paper had to buy a revenue stamp for it. Image (a) shows a partial proof sheet of one-penny stamps. Image (b) provides a close-up of a one-penny stamp. (credit a: modification of work by the United Kingdom Government; credit b: modification of work by the United Kingdom Government)

The Stamp Act signaled a shift in British policy after the French and Indian War. Before the Stamp Act, the colonists had paid taxes to their colonial governments or indirectly through higher prices, not directly to the Crown’s appointed governors. The passage of the Stamp Act meant that starting on November 1, 1765, the colonists would contribute £60,000 per year—17 percent of the total cost—to the upkeep of the ten thousand British soldiers in North America. Because the Stamp Act raised constitutional issues, it triggered the first serious protest against British Imperial policy in the colonies.

Figure 3. The announcement of the Stamp Act, seen in this newspaper publication (a), raised numerous concerns among colonists in America. Protests against British Imperial policy took many forms, such as this mock stamp (b) whose text reads “An Emblem of the Effects of the STAMP. O! the Fatal STAMP.”

Watch It

This video highlights the reasoning for the Stamp Act and the colonial reactions to it.

You can view the transcript for “The Stamp Act” here (opens in new window).

The Quartering Act

Parliament also asserted its colonial authority in 1765 with the Quartering Act. The Quartering Act of 1765 addressed the problem of housing British soldiers stationed in the American colonies. It required that they be provided with barracks or places to stay in public houses and that if extra housing were necessary, then troops could be stationed in barns and other uninhabited private buildings. In addition, the costs of the troops’ food and lodging fell to the colonists. Since the time of King James II (1685 -1688) many British subjects had mistrusted the presence of a standing army during peacetime, and having to pay for the soldiers’ lodging and food was especially burdensome. Widespread disregard for the law occurred in almost all the colonies, but the issue was especially contentious in New York, the headquarters of the British forces. When 1500 troops arrived in New York in 1766, the New York Assembly refused to follow the Quartering Act.

Colonial Protest: Gentry, Merchants, and the Stamp Act Congress

For many British colonists living in America, the Stamp Act raised serious civil liberties concerns. As a direct tax, it appeared to be an unconstitutional measure, one that deprived freeborn British citizens of the rights and privileges they enjoyed as British subjects, including the right to representation. According to the British Constitution, only representatives for whom British subjects voted could tax them. Parliament was in charge of taxation, and although it was a representative body, the colonies did not have direct representation in it. Parliamentary members who supported the Stamp Act argued that the colonists had virtual representation because the architects of the British Empire knew best how to maximize returns from its possessions overseas. However, this argument did not satisfy the protesters, who viewed themselves as having the same right as all British subjects to avoid taxation without their consent. With no representation in the House of Commons, where bills of taxation originated, they felt deprived of this inherent right.

Figure 4. Patrick Henry Before the Virginia House of Burgesses (1851), painted by Peter F. Rothermel, offers a romanticized depiction of Henry’s speech denouncing the Stamp Act of 1765. Supporters and opponents alike debated the stark language of the speech, which quickly became legendary.

The British government knew the colonists might object to the Stamp Act’s expansion of parliamentary power, but Parliament believed the relationship of the colonies to the Empire was one of dependence. However, the Stamp Act had the unintended consequence of drawing together colonists from very different backgrounds in protest. In Massachusetts, James Otis, a lawyer and defender of British liberty, became the leading voice for the idea that “taxation without representation is tyranny.” In the Virginia House of Burgesses, firebrand and enslaver Patrick Henry introduced the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions, which denounced the Stamp Act and the British crown in language so strong that some conservative Virginians accused him of treason. Henry replied that Virginians were subject only to taxes that they themselves—or their representatives—imposed. In short, there could be no taxation without representation. The colonists had never before formed a unified political front, so Grenville and Parliament did not fear true revolt until 1765.

In response to the Stamp Act, the Massachusetts Assembly sent letters to the other colonies, asking them to attend a meeting, or congress, to discuss how to respond to the act. Many American colonists from different colonies found common cause in their opposition to the Stamp Act. Representatives (including Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Thomas Hutchinson, Philip Livingston, and James Otis, among others) from nine colonial legislatures met in New York in the fall of 1765 to reach a consensus on whether Parliament could impose taxation without representation. The members of this first congress, known as the Stamp Act Congress, said no. These nine representatives had a vested interest in repealing the tax. Not only did it weaken their businesses and the colonial economy, but it also threatened their liberty under the British Constitution. They drafted a rebuttal to the Stamp Act, making clear that they desired only to protect their liberty as loyal subjects of the Crown. The document, called the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, outlined the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and trials without juries. Meanwhile, a popular protest was also gaining force.

The Stamp Act Congress issued the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which, like the Virginia Resolves, declared allegiance to the king and “all due subordination” to Parliament but also reasserted the idea that colonists were entitled to the same rights as British citizens living on British soil. Those rights included trial by jury, which had been abridged by the Sugar Act, and the right to be taxed only by their own elected representatives. As Daniel Dulany wrote in 1765: “It is an essential principle of the English constitution, that the subject shall not be taxed without his consent.”[1] Benjamin Franklin called it the “prime Maxim of all free Government.”[2] Because the colonies did not elect members to Parliament, they believed that they were not represented and could not be taxed by that body. The colonists rejected Parliament’s notion of virtual representation, with one pamphleteer calling it a “monstrous idea.”[3]

Link to Learning

Browse the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society to examine digitized primary sources of the documents that paved the way to the fight for liberty, such as Virginia’s Resolves.

Try It

Mobilization Against the Stamp Act

The Stamp Act Congress was a gathering of landowning, educated White men who represented the political elite of the colonies and were the colonial equivalent of the British landed aristocracy. While these upper-class men were drafting their grievances during the Stamp Act Congress, other colonists showed their distaste for the new act by boycotting British goods and protesting in the streets. Two groups, the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty, led the popular resistance to the Stamp Act.

Figure 5. With this broadside of December 17, 1765, the Sons of Liberty call for the resignation of Andrew Oliver, the Massachusetts Distributor of Stamps.

Forming in Boston in the summer of 1765, the Sons of Liberty were artisans, shopkeepers, and small-time merchants willing to adopt extralegal means of protest. Before the act had even gone into effect, the Sons of Liberty began protesting. On August 14, they took aim at Andrew Oliver, who had been named the Massachusetts Distributor of Stamps. After hanging Oliver in effigy—that is, using a crudely made figure as a representation of Oliver—the unruly crowd stoned and ransacked his house, finally beheading the effigy and burning the remains. Such a brutal response shocked the royal governmental officials, who hid until the violence had spent itself. Andrew Oliver resigned the next day. By that time, the mob had moved on to the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson who, because of his support of Parliament’s actions, was considered an enemy of colonial liberty. The Sons of Liberty barricaded Hutchinson in his home and demanded that he renounce the Stamp Act; he refused, and the protesters looted and burned his house. Furthermore, the Sons (also called “True Sons” or “True-born Sons” to make clear their commitment to liberty and distinguish them from the likes of Hutchinson) continued to lead violent protests with the goal of securing the resignation of all appointed stamp collectors.

Starting in early 1766, the Daughters of Liberty protested the Stamp Act by refusing to buy British goods and encouraging others to do the same. They avoided British tea, opting to make their own teas with local herbs and berries. They built a community—and a movement—around creating homespun cloth instead of buying British linen. Well-born women held “spinning bees,” at which they competed to see who could spin the most and the finest linen. An entry in The Boston Chronicle of April 7, 1766, states that on March 12, in Providence, Rhode Island, “18 Daughters of Liberty, young ladies of good reputation, assembled at the house of Doctor Ephraim Bowen, in this town. . . . There they exhibited a fine example of industry, by spinning from sunrise until dark, and displayed a spirit for saving their sinking country rarely to be found among persons of more age and experience.” At dinner, they “cheerfully agreed to omit tea, to render their conduct consistent. Besides this instance of their patriotism, before they separated, they unanimously resolved that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional, that they would purchase no more British manufactures unless it be repealed, and that they would not even admit the addresses of any gentlemen should they have the opportunity, without they determined to oppose its execution to the last extremity, if the occasion required.”

The Daughters’ boycott movement broadened the protest against the Stamp Act, giving women a new and active role in political dissent. Women were responsible for purchasing goods for the home, so by exercising the power of the purse, they could wield more power than they had in the past. Although they could not vote, they could mobilize others and make a difference in the political landscape.

link to learning

Esther de Berdt Reed was born and raised in London but moved to Philadelphia when she married an American colonist. She became active in raising money for the Continental Army during the American Revolution and her husband, Joseph Reed, was George Washington’s aide-de-camp.

In 1780, Esther published a pamphlet titled Sentiments of an American Woman, which explained her own reasons for supporting the Revolution and her belief that men and women were equal in their feelings of patriotism and desire for liberty:

“Our ambition is kindled by the same of those heroines of antiquity, who have rendered their sex illustrious, and have proved to the universe, that, if the weakness of our Constitution, if opinion and manners did not forbid us to march to glory by the same paths as the Men, we should at least equal, and sometimes surpass them in our love for the public good. I glory in all that which my sex has done great and commendable.”

– Esther de Berdt Reed, Sentiments of an American Woman, 1780

Escalation of Protests

From a local movement, the protests of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty soon spread until there was a chapter in every colony. The Daughters of Liberty promoted the boycott on British goods while the Sons enforced it, threatening retaliation against anyone who bought imported goods or used stamped paper. In the protest against the Stamp Act, wealthy political figures like John Adams supported the goals of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, even if they did not engage in the Sons’ violent actions.

These men, who were lawyers, printers, and merchants, ran a propaganda campaign parallel to the Sons’ campaign of violence. In newspapers and pamphlets throughout the colonies, they published article after article outlining the reasons the Stamp Act was unconstitutional and urging peaceful protest. They officially condemned violent actions but did not have the protesters arrested; a degree of cooperation prevailed, despite the groups’ different economic backgrounds. Certainly, all the protesters saw themselves as standing up against the corruption that threatened their liberty.

Figure 6. This 1766 illustration shows a funeral procession for the Stamp Act. Reverend William Scott leads the procession of politicians who had supported the act, while a dog urinates on his leg. George Grenville, pictured fourth in line, carries a small coffin. What point do you think this cartoon is trying to make?

The Declaratory Act

Back in Great Britain, news of the colonists’ reactions worsened an already volatile political situation. Grenville’s imperial reforms had brought increased domestic taxes and his unpopularity led to his dismissal by King George III. While many in Parliament still wanted such reforms, British merchants argued strongly for their repeal. These merchants had no interest in the philosophy behind the colonists’ desire for liberty; rather, their motive was financial: the boycott of British goods by North American colonists was hurting their business. Many of the British at home were also appalled by the colonists’ violent reaction to the Stamp Act. Other Britons cheered what they saw as the vigorous defense of liberty by their counterparts in the colonies.

In March 1766, the new prime minister, Lord Charles Watson-Wentworth Rockingham, compelled Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. Colonists celebrated what they saw as a victory for their British liberty; in Boston, merchant John Hancock treated the entire town to drinks. However, to appease opponents of the repeal, who feared that it would weaken parliamentary power over the American colonists, Rockingham also proposed the Declaratory Act, which stated in no uncertain terms that Parliament’s power was supreme and that any laws the colonies passed to govern and tax themselves were null and void if they ran counter to Parliamentary law.

Link to Learning

Visit The Avalon Project to read the full text of the Declaratory Act, in which Parliament asserted the supremacy of parliamentary power.

Try It

Glossary

Daughters of Liberty: well-born British colonial women who led a boycott movement against the imported British goods which were taxed by the Stamp Act

Decleratory Act: a law passed by the British Parliament following their half-hearted repeal of the Stamp Act, which declared that the British government had full and primary authority over all colonial policy

direct representation: when citizens of a nation are allowed to participate in free elections to choose their own representatives, who then -theoretically- vote in those citizens’ best interests

direct tax: a tax that consumers pay directly, rather than through merchants’ higher prices

no taxation without representation: the principle, first articulated in the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions, that the colonists needed to be represented in Parliament if they were to be taxed

non-importation movement: a widespread colonial boycott of British goods

Sons of Liberty: artisans, shopkeepers, and small-time merchants who opposed the Stamp Act and considered themselves British patriots

Stamp Act Congress: a group of 9 colonial representatives who gathered to discuss their response to the Stamp Act. They drafted the Declaration of Rights and Grievances against the British government, outlining all the actions they believed deprived colonists of their civil liberties

- Dulany, Considerations on the Propriety of imposing Taxes in the British Colonies, 8 ↵

- “The Colonist’s Advocate: III, 11 January 1770,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-17-02-0009 ↵

- George Canning, A Letter to the Right Honourable Wills Earl of Hillsborough, on the Connection Between Great Britain and Her American Colonies (London: T. Becket, 1768), 9. ↵