Learning Objectives

- Identify the causes of the War of 1812

- Describe key events and turning points during the War of 1812

- Examine the political and social consequences of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 Begins

The British continued to harass American shipping, and Madison faced enormous pressure at home to do something to alleviate this situation, even if any action meant war. British support for Indian resistance further exacerbated the situation. Madison knew that on paper the United States was militarily no match for Great Britain. But Britain’s continuing attacks on American ships fueled the calls for action from the War Hawks in Congress, particularly Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. Madison, having done all he could to find a non-military solution, was finally pushed to call for a declaration of war on June 1, 1812, a declaration that won Congress’s subsequent approval.

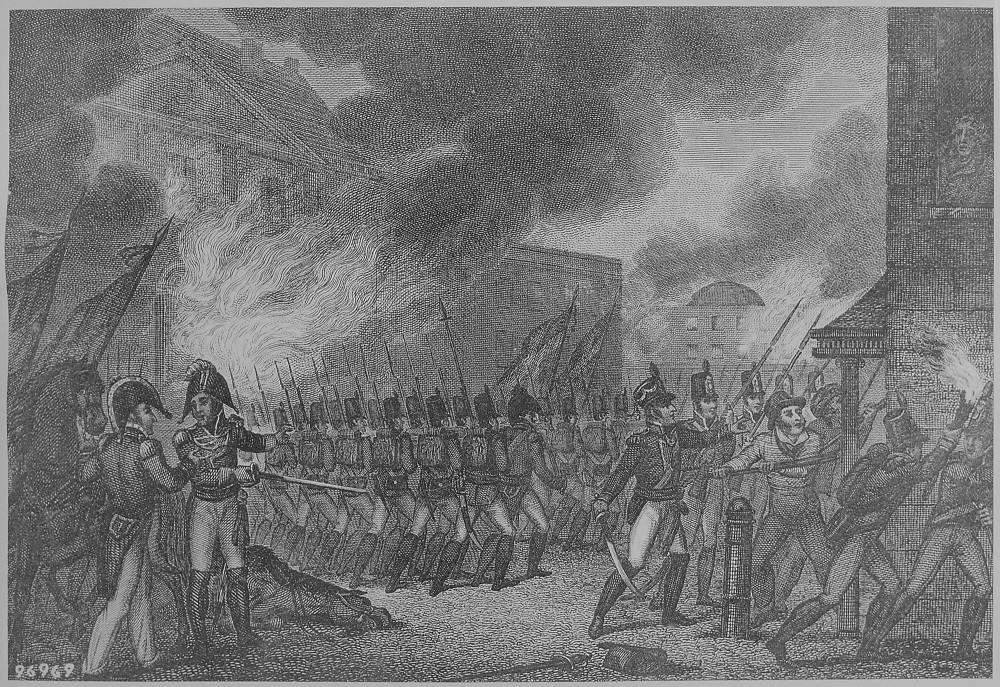

Figure 1. George Munger painted The President’s House shortly after the War of 1812, ca. 1814–1815. The painting shows the result of the British burning of Washington, DC.

In 1812, the Democratic-Republicans held 75 percent of the seats in the House and 82 percent of the Senate, giving them a free hand to set national policy. Among them were the “War Hawks,” whom one historian describes as “too young to remember the horrors of the American Revolution” and thus “willing to risk another British war to vindicate the nation’s rights and independence.” This group included men who would remain influential long after the War of 1812, such as Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Opposition to the war came from Federalists, especially those in the Northeast, who knew war would disrupt the maritime trade on which they depended. In a narrow vote, Congress authorized the president to declare war against Britain in June 1812.

While the War of 1812 contained two key players—the United States and Great Britain—it also drew in other groups, such as Tecumseh and his Confederacy. The war can be organized into three stages or theaters. The first, the Atlantic Theater, lasted until the spring of 1813. During this time, Great Britain was chiefly occupied in Europe against Napoleon, and the United States invaded Canada and sent their fledgling navy against British ships. During the second stage, from early 1813 to 1814, the United States launched their second offensive against Canada and the Great Lakes. In this period, the Americans won their first successes. The third stage, the Southern Theater, concluded with Andrew Jackson’s January 1815 victory outside New Orleans, Louisiana.

Try It

Watch it

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and Britain, lasting from 1812 to 1815. The war changed very little for the United States and Britain, but Native Americans suffered the biggest losses: their territory was taken and Tecumseh was killed.

You can view the transcript for “The War of 1812 – Crash Course US History #11” here (opens in new window).

The War Unfolds

During the war, the Americans were greatly interested in Canada and the Great Lakes borderlands. In July 1812, the U.S. launched their first offensive against Canada. By August, however, the British and their allies defeated the Americans in Canada, costing the U.S. control over Detroit and parts of the Michigan Territory. By the close of 1813, the Americans recaptured Detroit, shattered the Indian Confederacy, killed Tecumseh, and eliminated the British threat in that theater. Despite these accomplishments, the American land forces proved outmatched by their adversaries.

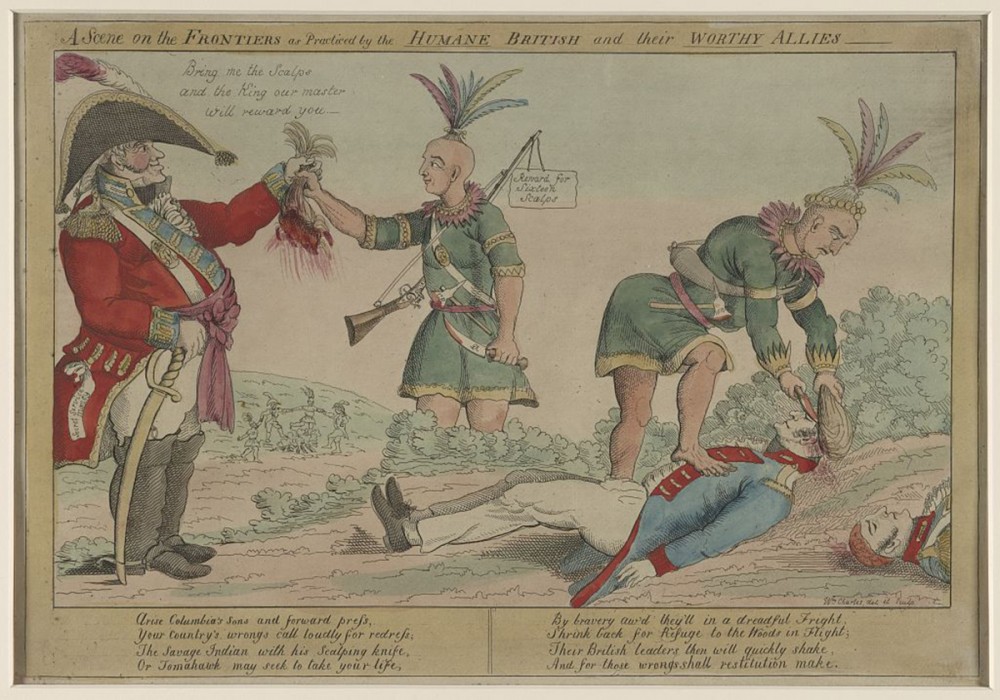

Figure 2. As pictured in this 1812 political cartoon published in Philadelphia, Americans lambasted the British and their native allies for what they considered “savage” offenses during war, though Americans too were engaging in such heinous acts.

After the land campaign of 1812 failed to secure America’s war aims, Americans turned to the infant navy in 1813. Privateers and the U.S. Navy rallied behind the slogan “Free Trade and Sailors Rights!” Although the British possessed the most powerful navy in the world, surprisingly the young American navy extracted early victories with larger, more heavily armed ships. By 1814, however, the major naval battles had been fought with little effect on the war’s outcome.

With Britain’s main naval fleet fighting in the Napoleonic Wars, smaller ships and armaments stationed in North America were generally no match for their American counterparts. Early on, Americans humiliated the British in single ship battles. In retaliation, Captain Phillip Broke, of the HMS Shannon attacked the USS Chesapeake captained by James Lawrence on June 1, 1813. Within six minutes, the Chesapeake was destroyed and Lawrence was mortally wounded. Yet, the Americans did not give up as Lawrence commanded them “Tell the men to fire faster! Don’t give up the ship!” Lawrence died of his wounds three days later and although the Shannon defeated the Chesapeake, Lawrence’s words became a rallying cry for the Americans.

Two and a half months later the USS Constitution squared off with the HMS Guerriere. As the Guerriere tried to outmaneuver the Americans, the Constitution pulled along broadside and began hammering the British frigate. The Guerriere returned fire, but as one sailor observed the cannonballs simply bounced off the Constitution’s thick hull. “Huzza! Her sides are made of iron!” shouted the sailor and henceforth, the Constitution became known as “Old Ironsides.” In less than thirty-five minutes, the Guerriere was so badly damaged it was set aflame rather than taken as a prize.

In 1814, Americans gained naval victories on Lake Champlain near Plattsburgh, preventing a British land invasion of the United States, and on the Chesapeake at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Fort McHenry repelled the nineteen-ship British fleet enduring twenty-seven hours of bombardment virtually unscathed. Watching from aboard a British ship, American poet Francis Scott Key penned the verses that would become the national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Francis Scott Key’s “In Defense of Fort McHenry”

After the British bombed Baltimore’s Fort McHenry in 1814 but failed to overcome the U.S. forces there, Francis Scott Key was inspired by the sight of the American flag, which remained hanging proudly in the aftermath. He wrote the poem “In Defense of Fort McHenry,” which was later set to the tune of a British song called “The Anacreontic Song” and eventually became the U.S. national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Oh, say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars, thru the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected, now shines on the stream:

Tis the star-spangled banner: O, long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a country should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.O, thus be it ever when freemen shall stand,

Between their loved home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav’n-rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: “In God is our trust”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!—Francis Scott Key, “In Defense of Fort McHenry,” 1814

What images does Key use to describe the American spirit? Most people are familiar with only the first verse of the song; what do you think the last three verses add?

Visit the Smithsonian Institute to explore an interactive feature on the flag that inspired “The Star-Spangled Banner,” where clickable “hot spots” on the flag reveal elements of its history.

Impressive though these accomplishments were, they belied what was actually a poorly executed military campaign against the British. The U.S. Navy won their most significant victories in the Atlantic Ocean in 1813. Napoleon’s defeat in early 1814, however, allowed the British to focus on North America and their blockade of the East coast. Thanks to the blockade, the British were able to burn Washington D.C. on August 24, 1814 and open a new theater of operations in the South.

Figure 3. The artist shows Washington D.C. engulfed in flames as the British troops set fire to the city in 1813.

Following the defeat of France, Britain no longer had to concern itself with stopping the United States from trade with its enemy, and pursued peace negotiations. The Treaty of Ghent ended the war and was signed in Europe on December 24, 1814. Due to slow communication, the last battle in the War of 1812 happened after the treaty had been signed. Andrew Jackson had distinguished himself in the war by defeating the Creek Indians in March 1814 before invading Florida in May of that year. After taking Pensacola, he moved his force of Tennessee fighters to New Orleans to defend the strategic port against British attack. On January 8, 1815 (despite the official end of the war), a force of battle-tested British veterans of the Napoleonic Wars attempted to take the port. Jackson’s forces devastated the British, killing over two thousand. New Orleans and the vast Mississippi River Valley had been successfully defended, ensuring the future of American settlement and commerce. The Battle of New Orleans immediately catapulted Jackson to national prominence as a war hero, and in the 1820s, he emerged as the head of the new Democratic Party.

The Hartford Convention

But not all Americans supported the war. In 1814, New England Federalists met in Hartford, Connecticut, to try to end the war and curb the power of the Democratic-Republican Party. They produced a document that proposed abolishing the three-fifths rule in the Constitution that afforded Southern slaveholders disproportionate representation in Congress, limiting the president to a single term in office, and most importantly, demanding a two-thirds congressional majority, rather than a simple majority, for legislation that declared war, admitted new states into the Union, or regulated commerce. With the two-thirds majority, New England’s Federalist politicians believed they could limit the power of their political foes.

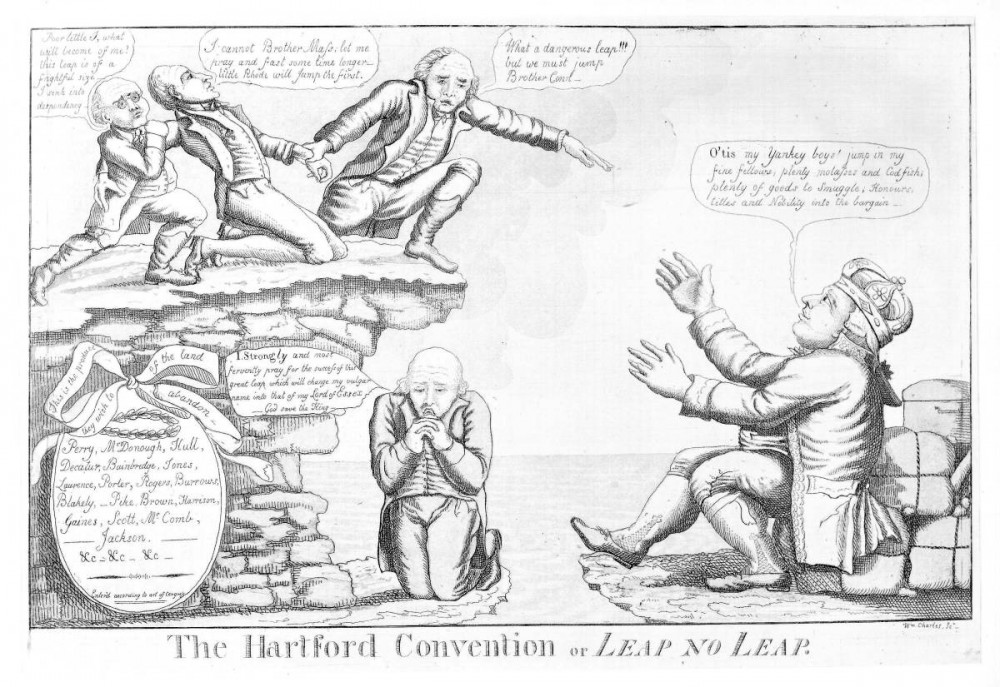

Figure 4. Contemplating the possibility of secession over the War of 1812 (fueled in large part by economic interests of New England merchants), the Hartford Convention posed the possibility of disaster for the still-young United States. England, represented by the figure John Bull on the right side, is shown in this political cartoon with arms open to accept New England back into its empire.

These proposals were sent to Washington, but unfortunately for the Federalists, the victory at New Orleans buoyed popular support for the Madison administration. With little evidence, newspapers accused the Hartford Convention’s delegates of plotting secession. The episode demonstrated the waning power of Federalism and the need for the region’s politicians to shed their aristocratic and Anglophile image. The next New England politician to assume the presidency, John Quincy Adams in 1824, would emerge not from within the Federalist fold, but after serving as Secretary of State under President James Monroe, the last leader of the Virginia Democratic-Republicans.

After the War

The Treaty of Ghent essentially returned relations between the U.S. and Britain to their pre-war status. The war, however, mattered politically and strengthened American nationalism. During the war, Americans read patriotic newspaper stories, sang patriotic songs, and bought consumer goods decorated with national emblems. They also heard stories about how the British and their Native allies threatened to bring violence into American homes. For example, rumors spread that British officers promised rewards of “beauty and booty” for their soldiers when they attacked New Orleans. In the Great Lakes borderlands, wartime propaganda fueled Americans’ fear of Britain’s Native American allies, who they believed would slaughter men, women, and children indiscriminately. Terror and love worked together to make American citizens feel a stronger bond with their country. Because the war mostly cut off America’s trade with Europe, it also encouraged Americans to see themselves as different and separate; it fostered a sense that the country had been reborn.

Former treasury secretary Albert Gallatin claimed that the War of 1812 revived “national feelings” that had dwindled after the Revolution. “The people,” he wrote, were now “more American; they feel and act more like a nation.” Politicians proposed measures to reinforce the fragile Union through capitalism and built on these sentiments of nationalism. The United States continued to expand into Indian territories with westward settlement in far-flung new states like Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Illinois. Between 1810 and 1830, the country added more than 6,000 new post offices.

In 1817, South Carolina congressman John C. Calhoun called for building projects to “bind the republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” He joined with other politicians, such as Kentucky’s powerful Henry Clay, to promote what came to be called an “American System.” They aimed to make America economically independent and encouraged commerce between the states over trade with Europe and the West Indies. The American System would include a new Bank of the United States to provide capital; a high protective tariff, which would raise the prices of imported goods and help American-made products compete; and a network of “internal improvements,” roads and canals to let people take American goods to market.

These projects were controversial. Many people believed they were unconstitutional or that they would increase the federal government’s power at the expense of the states. Even Calhoun later changed his mind and joined the opposition. The War of 1812, however, had reinforced Americans’ sense of the nation’s importance in their political and economic life. Even when the federal government did not act, states created banks, roads, and canals of their own.

What may have been the boldest declaration of America’s postwar pride came in 1823. President James Monroe issued an ultimatum to the empires of Europe in order to support independence in Latin America. The “Monroe Doctrine” declared that the United States considered its entire hemisphere, both North and South America, off-limits to new European colonization. Although Monroe was a Jeffersonian, some of his principles echoed Federalist policies. Whereas Jefferson cut the size of the military and ended all internal taxes in his first term, Monroe advocated the need for a strong military and an aggressive foreign policy. Since Americans were spreading out over the continent, Monroe authorized the federal government to invest in canals and roads, which he said would “shorten distances, and, by making each part more accessible to and dependent on the other…shall bind the Union more closely together.” As Federalists had attempted two decades earlier, Democratic-Republican leaders after the War of 1812 advocated strengthening the state in order to strengthen the nation.

Try It

Glossary

American System: a plan to encourage internal trade and make the United States economically independent through creation of a new Bank of the United States, a high protective tariff, and a network of roads and canals to ease the movement of goods to market

Hartford Convention: 1814 meeting of Federalists in Hartford, Connecticut. Their opposition to the War of 1812 would result in Americans viewing them as traitorous and mark the end of the Federalists as a force for political action

Monroe Doctrine: President Madison’s position, put forth in 1823, and adopted by all subsequent administrations, that the Western Hemisphere was closed to new efforts at European colonization

War Hawks: members of Congress who supported a declaration of war against Britain, culminating in the War of 1812