Learning Objectives

- Describe major conflicts between New England colonists and Native Americans, including Pequot and King Philip’s War

Puritan Relationships with Native Peoples

Like their Spanish and French Catholic rivals, English Puritans in America took steps to convert Native peoples to their version of Christianity. John Eliot, the leading Puritan missionary in New England, urged Natives in Massachusetts to live in “praying towns” established by English authorities for converts who would ostensibly adopt the Puritan emphasis on the centrality of the Bible. In keeping with the Protestant focus on reading scripture, he translated the Bible into the local Algonquian language and published his work in 1663. Eliot hoped that as a result of his efforts, some of New England’s native inhabitants would become preachers.

Tensions had existed from the beginning between the Puritans and the Native people who controlled southern New England. Relationships deteriorated as the Puritans continued to expand their settlements aggressively and as European ways increasingly disrupted native life. These strains led to King Philip’s War (1675–1676), a massive regional conflict that was nearly successful in pushing the English out of New England.

WAtch IT

This video explains some of the major conflicts between the early colonists and the Native Americans, including the Pequot War and King Philip’s War.

You can view the transcript for “The Natives and the English – Crash Course US History #3” here (opens in new window).

The Pequot War

When the Puritans began to arrive in the 1620s and 1630s, local Algonquian peoples had viewed them as potential allies in the conflicts already simmering between rival native groups. In 1621, the Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, negotiated a peace treaty with the Pilgrims at Plymouth. In the 1630s, the Puritans in Massachusetts and Plymouth allied themselves with the Narragansett and Mohegan people against the Pequot, who had recently expanded their claims into southern New England.

In May 1637, an armed contingent of English Puritans from Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut colonies trekked into the New England wilderness. Referring to themselves as the “Sword of the Lord,” this military force intended to attack “that insolent and barbarous Nation, called the Pequots.” In the resulting violence, Puritans put the Mystic community to the torch, beginning with the north and south ends of the town. As Pequot men, women, and children tried to escape the blaze, other soldiers waited with swords and guns. One commander estimated that of the “four hundred souls in this Fort…not above five of them escaped out of our hands,” although another counted near “six or seven hundred” dead. In a span of less than two months, the English Puritans boasted that the Pequot “were drove out of their country, and slain by the sword, to the number of fifteen hundred.”

The foundations of the war lay within the rivalry between the Pequot, the Narragansett, and Mohegan, who battled for control of the fur and wampum trades. This rivalry eventually forced the English and Dutch to choose sides. The war remained a conflict of native interests and initiative, especially as the Mohegan hedged their bets on the English and reaped the rewards that came with displacing the Pequot.

Victory over the Pequot not only provided security and stability for the English colonies, but also propelled the Mohegan to new heights of political and economic influence as the primary power in New England.

Link to Learning

This JSTOR Daily article highlights how Puritan attitudes about Native Americans changed following the Pequot War, and how this led some colonists to justify their enslavement.

King Philip’s War

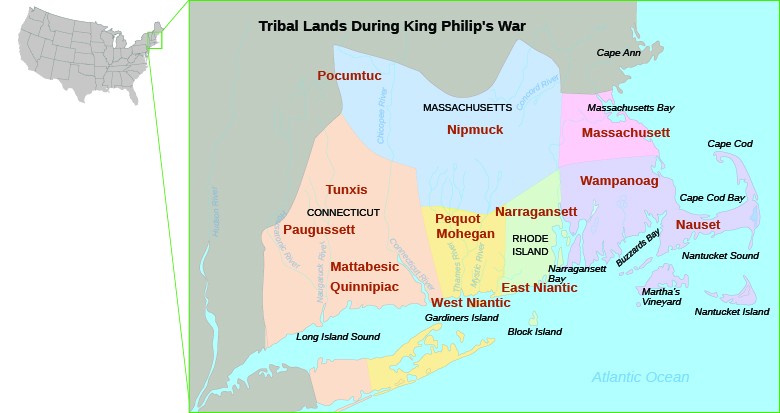

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Puritans had pushed their way further into the interior of New England, establishing outposts along the Connecticut River Valley. There seemed no end to their expansion. Wampanoag leader Metacom or Metacomet, also known as King Philip among the English, was determined to stop the encroachment. The Wampanoag, along with the Nipmuck, Pocumtuck, and Narragansett, took up the hatchet to drive the English from the land. In the ensuing conflict, called King Philip’s War, native forces succeeded in destroying half of the frontier Puritan towns; however, in the end, the English (aided by Mohegans and Indigenous Christian converts) prevailed and sold many captives into slavery in the West Indies.

Figure 1. This map indicates the domains of New England’s native inhabitants in 1670, a few years before King Philip’s War.

In the winter of 1675, the body of John Sassamon, a Christian, Harvard-educated Wampanoag, was found under the ice of a nearby pond. A fellow Native Christian convert informed English authorities that three warriors under the local sachem, Metacom, known to the English as King Philip, had killed Sassamon, who had previously accused Metacom of planning an insurrection against the English. The three alleged killers appeared before the Plymouth court in June 1675, were found guilty of murder, and executed. Several weeks later, a group of Wampanoags killed nine English colonists in the town of Swansea.

Metacom—like most other New England sachems—had entered into covenants of “submission” to various colonies, viewing the arrangements as relationships of protection and reciprocity rather than subjugation. Indians and English lived, traded, worshiped, and arbitrated disputes in close proximity before 1675, but the execution of three of Metacom’s men at the hands of Plymouth Colony epitomized what many Indigenous people viewed as a growing inequality of that relationship. The Wampanoags who attacked Swansea may have sought to restore balance, or to retaliate for the recent executions. Neither they nor anyone else sought to engulf all of New England in war, but that is precisely what happened. Authorities in Plymouth sprung into action, enlisting help from the neighboring colonies of Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Metacom and his followers eluded colonial forces in the summer of 1675, striking more Plymouth towns as they moved northwest. Some groups joined his forces, while others remained neutral or supported the English. The war badly divided some tribal communities. Metacom himself had little control over events, as panic and violence spread throughout New England in the autumn of 1675. English mistrust of neutral tribes, sometimes accompanied by demands they surrender their weapons, pushed many into open war. By the end of 1675, most of the Natives of western and central Massachusetts had entered the war, laying waste to nearby English towns like Deerfield, Hadley, and Brookfield. Hapless colonial forces, spurning the military assistance of Native allies such as the Mohegans, proved unable to locate more mobile native villages or intercept attacks.

The English compounded their problems by attacking the powerful and neutral Narragansetts of Rhode Island in December 1675. In an action called the Great Swamp Fight, a thousand Englishmen put the main Narragansett village to the torch, gunning down as many as a thousand Narragansett men, women, and children as they fled the maelstrom. The surviving Narragansetts joined the Native forces already in rebellion against the English. Between February and April 1676, rebels devastated a succession of English towns closer and closer to Boston.

Mary Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative

Mary Rowlandson was a Puritan woman whom native tribes captured and imprisoned for several weeks during King Philip’s War. After her release, she wrote The Narrative of the Captivity and the Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, which was published in 1682. The book was an immediate sensation that was reissued in multiple editions for over a century.

Figure 2. Puritan woman Mary Rowlandson wrote her captivity narrative, the front cover of which is shown here (a), after her imprisonment during King Philip’s War. In her narrative, she tells of her treatment by the Indians holding her as well as of her meetings with the Wampanoag leader Metacom (b), shown in a contemporary portrait.

But now, the next morning, I must turn my back upon the town, and travel with them into the vast and desolate wilderness, I knew not whither. It is not my tongue, or pen, can express the sorrows of my heart, and bitterness of my spirit that I had at this departure: but God was with me in a wonderful manner, carrying me along, and bearing up my spirit, that it did not quite fail. One of the Indians carried my poor wounded babe upon a horse; it went moaning all along, “I shall die, I shall die.” I went on foot after it, with sorrow that cannot be expressed. At length I took it off the horse, and carried it in my arms till my strength failed, and I fell down with it. Then they set me upon a horse with my wounded child in my lap, and there being no furniture upon the horse’s back, as we were going down a steep hill we both fell over the horse’s head, at which they, like inhumane creatures, laughed, and rejoiced to see it, though I thought we should there have ended our days, as overcome with so many difficulties. But the Lord renewed my strength still, and carried me along, that I might see more of His power; yea, so much that I could never have thought of, had I not experienced it.

What sustains Rowlandson during her ordeal? How does she characterize her captors? What do you think made her narrative so compelling to readers?

Access the entire text of Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative at the Gutenberg Project.

In the spring of 1676, the tide turned. The New England colonies took the advice of men like Benjamin Church, who urged the greater use of native allies to find and fight the mobile rebels. Unable to plant crops and forced to live off the land, the rebels’ will to fight waned as companies of English and native allies pursued them. Growing numbers of rebels fled the region, switched sides, or surrendered in the spring and summer. The English sold many of the latter group into slavery. Colonial forces finally caught up with Metacom in August 1676, and the sachem was slain by an Indigenous Christian convert fighting with the English. After his death, his wife and nine-year-old son were captured and sold as slaves in Bermuda. Philip’s head was mounted on a pike at the entrance to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where it remained for more than two decades.

The war permanently altered the political and demographic landscape of New England. Between 800 and 1000 English and at least 3000 Indigenous people perished in the 14-month conflict. Thousands of other Natives fled the region or were sold into slavery. In 1670, Native Americans comprised roughly 25 percent of New England’s population; a decade later, they made up perhaps 10 percent. The war’s brutality also encouraged a growing hatred of all Natives among many New England colonists; from then on, Puritan writers took great pains to vilify the natives as bloodthirsty savages. A new type of racial hatred became a defining feature of Indigenous-English relationships in the Northeast. Though the fighting ceased in 1676, the bitter legacy of King Philip’s War lived on.

Native-English Relations in the 18th Century

Yamasee War

In 1715, The Yamasees, Carolina’s closest allies and most lucrative trading partners, turned against the colony and very nearly destroyed it all. Writing from Carolina to London, the settler George Rodd believed they wanted nothing less than “the whole continent and to kill us or chase us all out.” Yamasees would eventually advance within miles of Charles Town.

The Yamasee War’s first victims were traders. The governor had dispatched two of the colony’s most prominent men to visit and pacify a Yamasee council following rumors of native unrest. Yamasees quickly proved the fears well founded by killing the emissaries and every English trader they could corral.

Yamasees, like many other natives, had come to depend on English courts as much as the flintlock rifles and ammunition traders offered them for slaves and animal skins. Feuds between English agents in Native territory had crippled the court of trade and shut down all diplomacy, provoking the violent Yamasee reprisal. Most native villages in the southeast sent at least a few warriors to join what quickly became a pan-tribal cause against the colony.

Yet Charles Town ultimately survived the onslaught by preserving one crucial alliance with the Cherokees. By 1717, the conflict had largely dried up, and the only remaining menace was roaming Yamasee bands operating from Spanish Florida. Most native villages returned to terms with Carolina and resumed trading. The lucrative trade in Indigenous slaves, however, which had consumed 50,000 souls in five decades, largely dwindled after the war. The danger was too high for traders, and the colonies discovered even greater profits by importing Africans to work new rice plantations. Herein lies the birth of the “Old South,” that hoard of plantations that created untold wealth and misery. Indigenous people retained the strongest militaries in the region, but they never again threatened the survival of English colonies.

Native and Colonist Relations in Pennsylvania

If there were a colony where peace with Indigenous people might continue, it would be in Pennsylvania, where William Penn created a religious imperative for the peaceful treatment of Indians. His successors, sons John, Thomas, and Richard, continued the practice but increased immigration, and booming land speculation increased the demand for land. The Walking Purchase of 1737, a deal made between members of the Delaware tribe and the proprietary government in an effort to secure a large tract of land for the colony north of Philadelphia in the Delaware and Lehigh River valleys, became emblematic of both colonials’ desire for cheap land and the changing relationship between Pennsylvanians and their native neighbors.

Through treaty negotiation in 1737, native Delaware leaders agreed to sell Pennsylvania all of the land that a man could walk in a day and a half, a common measurement utilized by Delawares in evaluating distances. John and Thomas Penn, joined by the land speculator James Logan, hired a team of skilled runners to complete the “walk” on a prepared trail. The runners traveled from Wrightstown to present-day Jim Thorpe and proprietary officials then drew the new boundary line perpendicular to the runners’ route, extending northeast to the Delaware River. The colonial government thus measured out a tract much larger than the Delawares had originally intended to sell, roughly 1200 square miles. As a result, Delaware-proprietary relations suffered. Many Delawares left the lands in question and migrated westward to join Shawnees and other Delawares already living in the Ohio Valley. There, they established diplomatic and trade relationships with the French. Memories of the suspect purchase endured into the 1750s and became a chief point of contention between the Pennsylvanian government and Delawares during the upcoming Seven Years War.

Try It

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Metacomet. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metacomet. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rule Brittania. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/4-3-an-empire-of-slavery-and-the-consumer-revolution. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction