Learning Objectives

- Explain ways in which the West came to be mythologized in American culture

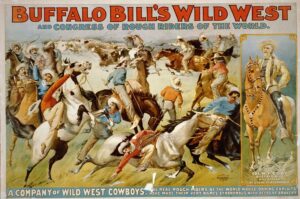

Figure 1. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World – Poster showing cowboys rounding up cattle and portrait of Col. W. F. Cody on horseback. c.1899.

Reading and Rodeos

“The American West” conjures visions of tipis, cabins, cowboys, Indians, farm wives in sunbonnets, and outlaws with six-shooters. Such images pervade American culture, but they are as old as the West itself: novels, rodeos, and Wild West shows mythologized the American West throughout the post–Civil War era.

Figure 2. Penguin classics cover of Owen Wister’s cowboy tale, The Virginian. This and other western novels created the image of the rugged American cowboy.

In the 1860s, Americans devoured dime novels that embellished the lives of real-life individuals such as Calamity Jane and Billy the Kid. Owen Wister’s novels, especially The Virginian, established the character of the cowboy as a gritty stoic with a rough exterior but the courage and heroism needed to rescue people from train robbers, Indians, and cattle rustlers. Such images were later reinforced when the emergence of rodeo added to popular conceptions of the American West. Rodeos began as small roping and riding contests among cowboys in towns near ranches or at camps at the end of the cattle trails. In Pecos, Texas, on July 4, 1883, cowboys from two ranches, the Hash Knife and the W Ranch, competed in roping and riding contests as a way to settle an argument; this event is recognized by historians of the West as the first real rodeo. Casual contests evolved into planned celebrations. Many were scheduled around national holidays, such as Independence Day, or during traditional roundup times in the spring and fall. Early rodeos took place in open grassy areas—not arenas—and included calf and steer roping and roughstock events such as bronco riding.

They gained popularity and soon dedicated rodeo circuits developed. Although about 90 percent of rodeo contestants were men, women helped popularize the rodeo and several popular female bronco riders, such as Bertha Kaepernick, entered men’s events, until around 1916 when women’s competitive participation was curtailed. Americans also experienced the “Wild West”—the mythical West imagined in so many dime novels—by attending traveling Wild West shows, arguably the unofficial national entertainment of the United States from the 1880s to the 1910s. Wildly popular across the country, the shows traveled throughout the eastern United States and even across Europe and showcased what was already a mythic frontier life.

Buffalo Bill and His Wild West Show

William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody was the first to recognize the broad national appeal of the stock “characters” of the American West—cowboys, Indians, sharpshooters, cavalrymen, and rangers—and put them all together into a single massive traveling extravaganza. Operating out of Omaha, Nebraska, Buffalo Bill launched his touring show in 1883. Cody himself shunned the word show, fearing that it implied an exaggeration or misrepresentation of the West. He instead called his production “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.” He employed real cowboys and Indians in his productions. But it was still, of course, a show. It was entertainment, little different in its broad outlines from contemporary theater. Storylines depicted westward migration, life on the Plains, and Indian attacks, all punctuated by “cowboy fun”: bucking broncos, roping cattle, and sharpshooting contests. Buffalo Bill, joined by shrewd business partners skilled in marketing, turned his shows into a sensation.

But he was not alone. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie, another popular Wild West showman, got his start in 1886 when Cody employed him as an interpreter for Pawnee members of the show. Lillie went on to create his own production in 1888, “Pawnee Bill’s Historic Wild West.” He was Cody’s only real competitor in the business until 1908 when the two men combined their shows to create a new extravaganza, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East” (most people called it the “Two Bills Show”). It was an unparalleled spectacle. The cast included American cowboys, Mexican vaqueros, Native Americans, Russian Cossacks, Japanese acrobats, and an Australian aboriginal.

Cody and Lillie knew that Native Americans fascinated audiences in the United States and Europe, and both featured them prominently in their Wild West shows. Most Americans believed that Native cultures were disappearing or had already, and felt a sense of urgency to see their dances, hear their songs, and be captivated by their bareback riding skills and their elaborate buckskin and feather attire. The shows certainly veiled the true cultural and historic value of so many Native demonstrations, and the Indian performers were curiosities to White Americans, but the shows were one of the few ways for many Native Americans to make a living in the late nineteenth century.

In an attempt to appeal to women, Cody recruited Annie Oakley, a female sharpshooter who thrilled onlookers with her many stunts. Billed as “Little Sure Shot,” she shot apples off her poodle’s head and the ash from her husband’s cigar, clenched trustingly between his teeth. Gordon Lillie’s wife, May Manning Lillie, also became a skilled shot and performed as “World’s Greatest Lady Horseback Shot.” Female sharpshooters were Wild West show staples. As many as eighty toured the country at the shows’ peaks. But if such acts challenged expected Victorian gender roles, female performers were typically careful to blunt criticism by maintaining their feminine identity—for example, by riding sidesaddle and wearing full skirts and corsets—during their acts.

The western “cowboys and Indians” mystique, perpetuated in novels, rodeos, and Wild West shows, was rooted in romantic nostalgia and, perhaps, in the anxieties that many felt in the late nineteenth century’s new seemingly “soft” industrial world of factory and office work. The mythical cowboy’s “aggressive masculinity” was the seemingly perfect antidote for middle- and upper-class, city-dwelling Americans who feared they “had become over-civilized” and longed for what Theodore Roosevelt called the “strenuous life.” Roosevelt himself, a scion of a wealthy New York family and later a popular American president, turned a brief tenure as a failed Dakota ranch owner into a potent part of his political image. Americans looked longingly to the West, whose romance would continue to pull at generations of Americans.

Watch it

In this CrashCourse video, you’ll learn about the not-so-wild west, at least not the romanticized version of what we so often see portrayed in media. Instead of lone rangers, most came in family groups, and many came as immigrants or with businesses. Unfortunately, the Native Americans already living on the lands were displaced from their homes, oftentimes through violent and horrific means.

You can view the transcript for “Westward Expansion: Crash Course US History #24” here (opens in new window).

Try It

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Megan Coplen for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Westward Expansion: Crash Course US History #24. Provided by: Crash Course. Located at: https://youtu.be/Q16OZkgSXfM?t=1s. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- The West. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/17-conquering-the-west/#identifier_25_97. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike