Learning Objectives

- Explain the process of “Americanization” as it applied to Native Americans in the nineteenth century

“Americanization”

Through the years of the Indian Wars of the 1870s and early 1880s, opinion back east was mixed. General Philip Sheridan (appointed in 1867 to pacify the Plains Indians) famously said “the only good Indian is a dead Indian” and many agreed with him. But increasingly, several American reformers who would later form the backbone of the Progressive Era had begun to criticize the violence, arguing that the Indians should be helped through “Americanization” to become assimilated into American society. Individual land ownership, Christian worship, and education for children became the cornerstones of this new, and final, assault on Native American life and culture.

Figure 1. Tom Torlino, a member of the Navajo Nation, entered the Carlisle Indian School, a Native American boarding school founded by the United States, on October 21, 1882 and departed on August 28, 1886. Torlino’s student file contained photographs from 1882 and 1885.

Boarding Schools and Reeducation

Beginning in the 1880s, clergymen, government officials, and social workers all worked to assimilate Indians into American life. The government permitted reformers to remove Indian children from their homes and place them in boarding schools, such as the Carlisle Indian School or the Hampton Institute, where they were taught to abandon their tribal traditions and embrace American modesty, sanctity, and tools of productivity through total immersion. Such schools not only acculturated Indian boys and girls, but also provided vocational training for males and domestic science classes for females. Adults were also targeted by religious reformers, specifically evangelical Protestants as well as a number of Catholics, who sought to convince Indians to abandon their language, clothing, and social customs for a more Euro-American lifestyle.

Proselytizing to Native Americans

Figure 2. The federal government’s policy towards the Indians shifted in the late 1880s from relocating them to assimilating them into the American ideal. Indians were given land in exchange for renouncing their tribe, traditional clothing, and way of life.

Many female Christian missionaries played a central role in cultural reeducation programs that attempted to not only instill Protestant religion but also impose traditional American gender roles and family structures. They endeavored to replace Indians’ tribal social units with small, patriarchal households. Women’s labor became a contentious issue because few tribes divided labor according to the gender norms of middle- and upper-class Americans. Fieldwork, the traditional domain of white males, was primarily performed by Native women, who also usually controlled the products of their labor and often land that was worked, giving them status in society as laborers and food providers. For missionaries, the goal was to get Native women to leave the fields and engage in more proper “women’s work”—housework.

Christian missionaries performed much as secular federal agents had. Few American agents could meet Native Americans on their own terms. Most viewed reservation Indians as lazy and thought of Native cultures as inferior to their own. The views of J. L. Broaddus, appointed to oversee several small Indian tribes on the Hoopa Valley reservation in California, are illustrative of these prejudiced views: in his annual report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1875, he wrote, “The great majority of them are idle, listless, careless, and improvident. They seem to take no thought about provision for the future, and many of them would not work at all if they were not compelled to do so. They would rather live upon the roots and acorns gathered by their women than to work for flour and beef.”[1]

Link to Learning

Take a look at the Carlisle Industrial Indian School where Indian students were “civilized” from 1879 to 1918. It is worth looking through the photographs and records of the school to see how this program obliterated Indian culture. This Vox video also details how this happened.

Currently, the Carlisle Indian School Project is seeking to tell the stories of those who attended and give a voice to their legacy.

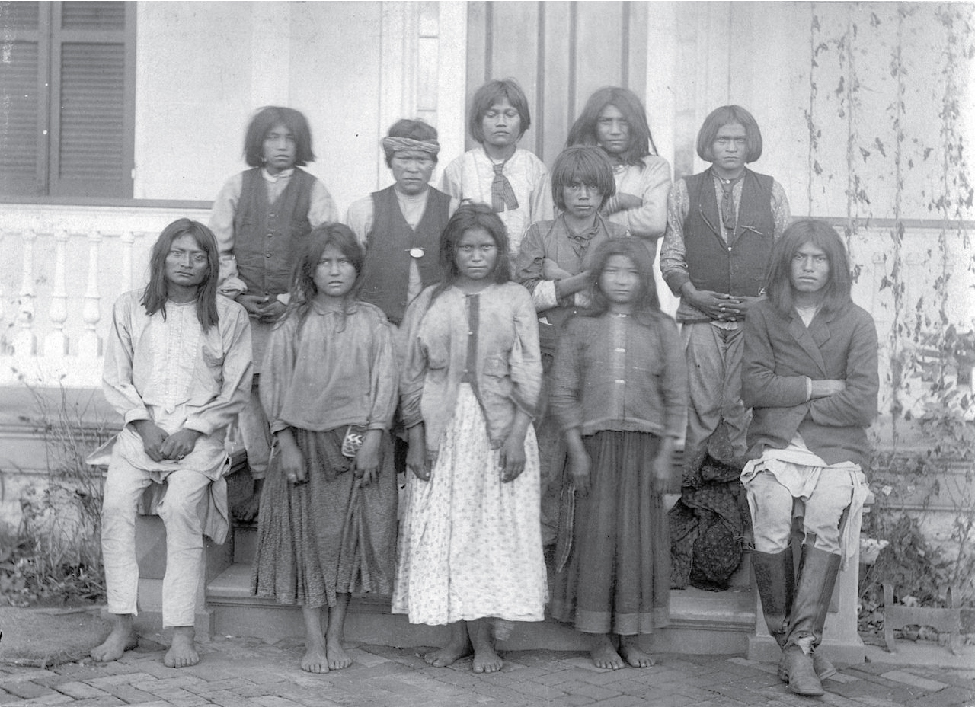

Figure 3. Eleven Apache boys and girls pose outside the Carlisle Indian School after their arrival in 1886.

Figure 4. The caption above the boys and girls reads, “Chiricahua Apaches Four Months After Arriving at Carlisle” and lists their names underneath.

Try It

The Allotment Era

As the rails moved into the West, and more and more Americans followed, the situation for Native groups deteriorated even further. Treaties negotiated between the United States and Native groups had typically promised that if tribes agreed to move to specific reservation lands, they would hold those lands collectively. But as American westward migration mounted and open lands closed, white settlers began to argue that Native people had more than their fair share of land, that the reservations were too big, that Native people were using the land “inefficiently,” and that they still preferred nomadic hunting instead of intensive farming and ranching.

By the 1880s, Americans increasingly championed legislation to allow the transfer of indigenous lands to farmers and ranchers, while many argued that allotting land to individual Native Americans, rather than to tribes, would encourage American-style agriculture and finally put Indians who had previously resisted the efforts of missionaries and federal officials on the path to “civilization.”

The Dawes General Allotment Act

Most Indian American belief structures did not allow for the concept of individual land ownership; rather, the land was available for all to use and required responsibility from all to protect it. As a part of their plan to Americanize the tribes, reformers sought legislation to replace this concept with the popular Euro-American notion of real estate ownership and self-reliance.

Figure 5. Red Cloud and American Horse – two of the most renowned Ogala chiefs – are seen clasping hands in front of a tipi on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Both men served as delegates to Washington, D.C., after years of actively fighting the American government. John C. Grabill, “‘Red Cloud and American Horse.’ The two most noted chiefs now living,” 1891. Library of Congress.

Passed by Congress on February 8, 1887, the Dawes General Allotment Act splintered Native American reservations into individual family homesteads. Each head of a Native family was to be allotted 160 acres, the typical size of a claim that any settler could establish on federal lands under the provisions of the Homestead Act. Single individuals over age eighteen would receive an eighty-acre allotment, and orphaned children received forty acres. A four-year timeline was established for Indian peoples to make their allotment selections. If at the end of that time no selection had been made, the act authorized the secretary of the interior to appoint an agent to make selections for the remaining tribal members. Allegedly to protect Indians from being swindled by unscrupulous land speculators, all allotments were to be held in trust—they could not be sold by allottees—for twenty-five years. Lands that remained unclaimed by tribal members after allotment would revert to federal control and be sold to American settlers. Only after 25 years could a Native landowner obtain the full title and be granted the citizenship rights that land ownership entailed. It would not be until 1924 that formal citizenship was granted to all Native Americans. Under the Dawes Act, Indians were given the most arid, useless land. Further, inefficiencies and corruption in the government meant that much of the land due to be allotted to Indians was simply deemed “surplus” and claimed by settlers. Once all allotments were determined, the remaining tribal lands—as much as eighty million acres—were sold to white American settlers.[2]

Americans touted the Dawes Act as an uplifting humanitarian reform, but it upended Native lifestyles and left Native nations without sovereignty over their lands. The act claimed that to protect Native property rights, it was necessary to extend “the protection of the laws of the United States . . . over the Indians.” Tribal governments and legal principles could be superseded, or dissolved and replaced, by U.S. laws. Under the terms of the Dawes Act, Native nations struggled to hold on to some measure of tribal sovereignty.

The “Last Arrow” Pageant

The final element of “Americanization” was the symbolic “last arrow” pageant, which often coincided with the formal redistribution of tribal lands under the Dawes Act. At these events, Indians were forced to assemble in their tribal garb, carrying a bow and arrow. They would then symbolically fire their “last arrow” into the air, enter a tent where they would strip away their Indian clothing, dress in a White farmer’s coveralls, and emerge to take a plow and an American flag to show that they had converted to a new way of life. It was a seismic shift for the Indians and one that left them bereft of their culture and history.

Try It

Glossary

Americanization: the process by which an Indian was “redeemed” and assimilated into the American way of life by changing his clothing to western clothing and renouncing his tribal customs in exchange for a parcel of land

Dawes Act: 1887 act that divided Native American reservations into individual homesteads, giving each family 160 acres

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Megan Coplen for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- The West. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/17-conquering-the-west/#identifier_25_97. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tom Torlino. Authored by: J. N. Choate. Image courtesy of the Richard Henry Pratt Papers, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tom_Torlino_Navajo_before_and_after_circa_1882.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Red Cloud and American Horse. Authored by: Grabill, John C. H.. Located at: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99613806/. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright