Learning Objectives

- Describe the ways social media influenced various social movements

- Describe conflicts associated with Donald Trump’s Presidency

The Presidency of Donald Trump

By 2016, American voters were fed up. In that year’s presidential race, Republicans spurned their political establishment and nominated a real estate developer and celebrity billionaire, Donald Trump, who, decrying the tyranny of political correctness and promising to Make America Great Again, promised to build a wall to keep out Mexican immigrants and bar Muslim immigrants. The Democrats, meanwhile, flirted with the candidacy of Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist from Vermont, before ultimately nominating Hillary Clinton, who, after eight years as first lady in the 1990s, had served eight years in the Senate and four more as secretary of state.

Voters despaired: Trump and Clinton were the most unpopular nominees in modern American history. Majorities of Americans viewed each candidate unfavorably and majorities in both parties said, early in the election season, that they were motivated more by voting against their rival candidate than for their own. With incomes frozen, politics gridlocked, race relations tense, and headlines full of violence, such frustrations only channeled a larger sense of stagnation, which upset traditional political allegiances. In the end, despite winning nearly three million more votes nationwide, Clinton failed to carry key Midwestern states where frustrated white, working-class voters abandoned the Democratic Party—a Republican president hadn’t carried Wisconsin, Michigan, or Pennsylvania, for instance, since the 1980s—and swung their support to the Republicans. Donald Trump won the presidency.

Figure 1. Donald Trump speaking at a 2018 rally. Photo by Gage Skidmore. Via Wikimedia.

Political divisions only deepened after the election. A nation already deeply split by income, culture, race, geography, and ideology continued to come apart. Trump’s presidency consumed national attention. Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian election meddling and the alleged collusion of campaign officials in that effort produced countless headlines.

American Cultural Divide Under Trump

Meanwhile, new policies enflamed widening cultural divisions. Border apprehensions and deportations reached record levels under the Obama administration, but Trump pushed even farther. He pushed for a massive wall along the border to supplement the fence built under the Bush administration. He began to order the deportation of American ‘Dreamers’, people who were born in other countries but grew up in The United States without documentation. Trump’s border policies heartened his base and aggravated his opponents. But while Trump fueled the value of xenophobia and nativism that many members of his base believed in, his narrowly passed 2017 tax cut continued the redistribution of American wealth toward corporations and wealthy individuals. The tax cut exploded the federal deficit and further exacerbated America’s widening economic inequality.

In his inaugural address, Donald Trump promised to end what he called “American carnage”—a nation ravaged, he said, by illegal immigrants, crime, and foreign economic competition. But, under his presidency, the nation only spiraled deeper into cultural and racial divisions, domestic unrest, and growing anxiety about the nation’s future. Trump represented an aggressive, pugilistic anti-liberalism, and, as president, never missing an opportunity to fuel on the fires of right-wing rage. Refusing to settle for the careful statement or defer to bureaucrats, Trump smashed many of the norms of the presidency and raged on his personal Twitter account.

Few Americans, especially after the Johnson and Nixon administrations, believed that presidents never lied. But perhaps no president ever lied so boldly or so often as Donald Trump, who made, according to one account, an untrue statement every day for the first forty days of his presidency. By the latter years of his presidency, only about a third of Americans counted him as trustworthy. And that compulsive dishonesty led directly to January 6, 2021.

2021 United States Capitol Attack

In November 2020, Joseph R. Biden, a longtime senator from Delaware and former Vice President under Barack Obama, running alongside Kamala Harris, a California senator who would become the nation’s first female vice president, convincingly defeated Donald Trump at the polls: Biden won the popular vote by a margin of four percent and the electoral vote by a margin of 74 votes, marking the first time an incumbent president had been defeated in over thirty years. But Trump refused to concede the election. He said it had been stolen. He said votes had been manufactured. He said it was all rigged. The claims were easily debunked, but it didn’t seem to matter: months after the election, somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of self-identified Republicans judged the election stolen. So when, on the afternoon of January 6, 2021, the president again articulated a litany of lies about the election and told the crowd of angry conspiracy-minded protestors to march to the Capitol and “fight like hell,” they did.

Thousands of Trump’s followers converged on the Capitol. Roughly one in seven of the more than 500 rioters later arrested were affiliated with extremist groups organized around conspiracy theories, white supremacy, and the right-wing militia movement. They waved American and Confederate flags, displayed conspiracy theory slogans and white supremacist icons, carried Christian iconography, and, above all, bore flags, hats, shirts, and other emblazoned with the name of Donald Trump. Arming themselves for hand-to-hand combat, they pushed past barriers and battled barricaded police officers. The Capitol attackers injured about 150 of them. Officers suffered concussions, burns, bruises, stab wounds, and broken bones. One suffered a non-fatal heart attack after being shocked repeatedly by a stun gun. Capitol Police Officer Brian D. Sicknick was killed, either by repeated attacks with a fire extinguisher or from mace or bear spray. Four other officers later died by suicide.

As the rioters breached the building, officers inside the House chamber moved furniture to barricade the doors as House members huddled together on the floor, waiting for a breach. Ashli Babbitt, a thirty-five-year-old Air Force veteran consumed by social-media conspiracy theories, and wearing a Trump flag around her neck, was shot and killed by a Capitol Police officer when she attempted to storm the chamber. The House Chamber held, but attackers breached the Senate Chamber on the opposite end of the building. Lawmakers had already been evacuated.

The rioters held the Capitol for several hours before the National Guard cleared it that evening. Congress, refusing to back down, stayed that evening to certify the results of the election. And yet, despite everything that had happened the day, the president’s unfounded claims of election fraud kept their grip on on Republican lawmakers. Eleven Republican senators and 150 of the House’s 212 Republicans lodged objections to the certification. A little more than a month later, they refused to convict Donald Trump during his quickly organized second impeachment trial, this time for “incitement of insurrection.”

The COVID-19 Pandemic

In the winter of 2019 and 2020, a new respiratory virus emerged in Wuhan, China. It was a coronavirus, named after its spiky, crown-like appearance under a microscope. Other coronaviruses had been identified and contained in previous years, but, by December, Chinese doctors were treating dozens of cases, and, by January, hundreds. Wuhan shut down to contain the outbreak but the virus escaped. By January, the United States confirmed its first case in New Rochelle, N.Y. Deaths were reported in the Philippines and in France. Outbreaks struck Italy and Iran. And American case counts grew. Countries began locking down. Air travel slowed.

The virus was highly contagious and could be spread before the onset of symptoms. Many who had the virus were asymptomatic—they didn’t exhibit any symptoms at all. But others, especially the elderly and those with “co-morbidities,” were devastated. The virus attacked their airways, suffocating them. Doctors didn’t know what they were battling. They struggled to procure oxygen and respirators and incubated the worst cases with what they had. But the deaths piled up.

The virus hit New York City in the spring. The city was devastated. Hospitals overflowed as doctors struggled to treat a disease they barely understood. By April, thousands of patients were dying every day. The city couldn’t keep up with the bodies. Dozens of “mobile morgues” were set up to house bodies which wouldn’t be processed for months.[1]

With medical-grade masks in short supply, Americans made their own homemade cloth masks. Many right-wing Americans notably refused to wear them at all, further exposing workers and family members to the virus.

Failing to contain the outbreak, the country shut down. Flights stopped. Schools and restaurants closed. White-collar workers transitioned to working from home when offices shut down. But others weren’t so lucky. By April, 10 million Americans had lost their jobs.

But shutdowns were scattered and incomplete. States were left to fend for themselves, setting their own policies and competing with one another to acquire scarce personal protective equipment (PPE). Many workers couldn’t stay home. Hourly workers, lacking paid sick leave, often had to choose between a paycheck and reporting to work having been exposed or even when presenting symptoms. Mask-wearing, meanwhile, was politicized. By May, 100,000 Americans were dead. A new wave of cases hit the South in July and August, overwhelming hospitals across much of the region. But the worst came in the winter, when the outbreak went fully national. Hundreds of thousands tested positive for the virus every day and nearly three-thousand Americans died every day throughout January and much of February.

The outbreak retreated in the spring, and pharmaceutical labs, flush with federal dollars, released new, cutting-edge vaccines. By late spring, Americans were getting vaccinated by the millions. The virus looked like it could be defeated. But many Americans, variously swayed by conspiracy theories peddled on social media or simply politically radicalized into associating vaccinations with anti-Trump politics, refused them. By late summer, barely a majority of those eligible for vaccines were fully vaccinated. And so the pandemic continued on. More contagious strains spread and the virus continued churning through the population, sending the unvaccinated to hospitals and to early deaths.

In the spring and fall of 2021, two new variants of the COVID-19 virus known as the Delta and Omicron variants were discovered. Each variant was more contagious then the original virus, but the symptoms were less severe. Those who were fully vaccinated were still getting sick, and the vaccine companies began to produce ‘booster’ shots to increase protection. In most cities and states, mask mandates have been lifted, and vaccine mandates put into place. However, there is no federal cohesive policy on either. As of March 2022, 950,000 Americans have died of COVID-19.

Generation Y and Z

Americans looked anxiously to the future, and yet also, often, to a new generation busy discovering, perhaps, that change was not impossible. Much public commentary in the early twenty-first century concerned “Millennials” and “Generation Z,” the generations that came of age during the new millennium. Commentators, demographers, and political prognosticators continued to ask what the new generation will bring. Time’s May 20, 2013, cover, for instance, read Millennials Are Lazy, Entitled Narcissists Who Still Live with Their Parents: Why They’ll Save Us All. Pollsters focused on features that distinguish millennials from older Americans: millennials, the pollsters said, were more diverse, more liberal, less religious, and wracked by economic insecurity. “They are,” as one Pew report read, “relatively unattached to organized politics and religion, linked by social media, burdened by debt, distrustful of people, in no rush to marry—and optimistic about the future.”[2]

While liberal social attitudes marked the younger generation, perhaps nothing defined young Americans more than the embrace of technology. The Internet in particular, liberated from desktop modems, shaped more of daily life than ever before. The release of the Apple iPhone in 2007 popularized the concept of smartphones for millions of consumers and, by 2011, about a third of Americans owned a mobile computing device. Four years later, two-thirds did.

Race & Gender in the 21st Century

Together with the advent of social media, Americans used their smartphones and their desktops to stay in touch with old acquaintances, chat with friends, share photos, and interpret the world—as newspaper and magazine subscriptions dwindled, Americans increasingly turned to their social media networks for news and information. Ambitious new online media companies, hungry for clicks and the ad revenue they represented, churned out provocatively titled, easy-to-digest stories that could be linked and tweeted and shared widely among like-minded online communities, but even traditional media companies, forced to downsize their newsrooms to accommodate shrinking revenues, fought to adapt to their new online consumers.

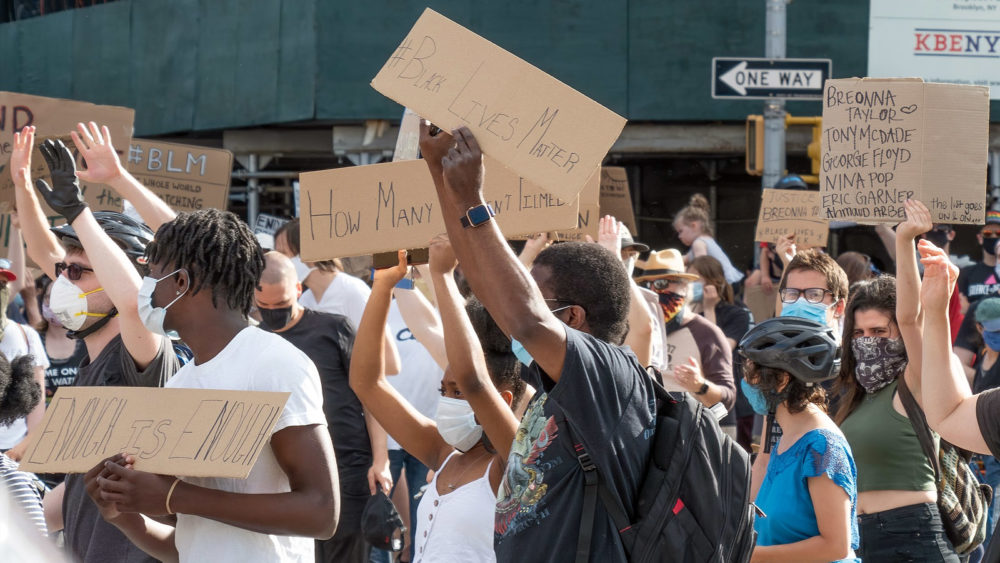

The ability of individuals to share stories through social media apps revolutionized the media landscape—smartphone technology and the democratization of media reshaped political debates and introduced new political questions. The easy accessibility of video capturing and the ability for stories to go viral outside traditional media, for instance, brought new attention to the tense and often violent relations between municipal police officers and African Americans. The 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked protests and focused the issue. It perhaps became a testament to the power of social media platforms such as Twitter that a hashtag, #blacklivesmatter, became a rallying cry for protesters and counter hashtags, #alllivesmatter and #policelivesmatter, for critics. But a relentless number of videos documenting the deaths of Black men at the hands of police officers continued to circulated across social media networks. The deaths of Eric Garner, twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, and Philando Castile, were captured on cell phone cameras and went viral. So too did the stories of Breonna Taylor and Botham Jean. “Say their names,” a popular chant at Black Lives Matters marches went. And then George Floyd was murdered.

Figure 2. George Floyd’s murder in 2020 sparked the largest protests in American history. Here, crowds holding homemade signs protest in New York City. Via Wikimedia.

George Floyd

On May 25, 2020, a teenager, Darnella Frazier, filmed Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin with his knee on the neck of George Floyd. “I can’t breath,” Floyd said. Despite his pleas, and those of bystanders, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes. Floyd’s body had long gone limp. The horrific footage shocked much of the country. Despite state and local lockdowns to slow the spread of Covid-19, spontaneous demonstrations broke out across the country. Protests erupted not only in major cities but in small towns and rural communities. The demonstrations dwarfed, in raw numbers, any comparable protest in American history. Taken together, as many as 25 million Americans may have participated in racial justice demonstrations that summer. And yet, despite the marches, no great national policy changes quickly followed.

The “system” resisted calls to address “systemic racism.” Localities made efforts, of course. Criminal justice reformers won elections as district attorneys. Police departments mandated their officers carry body cameras. As cries of “defund the police” sounded among left-wing Americans, some cities experimented with alternative emergency services that emphasized mediation and mental health. Meanwhile, at a symbolic level, Democratic-leaning towns and cities in the South pulled down their Confederate iconography. But the intractable racial injustices embedded deeply within American life had not been uprooted and racial disparities in wealth, education, health, and other measures persevered, as they already had, in the United States, for hundreds of years.

#MeToo

As the Black Lives Matter movement captured national attention, another social media phenomenon, the #MeToo movement, began as the magnification of and outrage toward the past sexual crimes of notable male celebrities before injecting a greater intolerance toward those accused of sexual harassment and violence into much of the rest of American society. The sudden zero tolerance reflected the new political energies of many American women, sparked in large part by the candidacy and presidency of Donald Trump. The day after Trump’s inauguration, between five hundred thousand and one million people descended on Washington, D.C., for the Women’s March, and millions more demonstrated in cities and towns around the country to show a broadly defined commitment toward the rights of women and others in the face of the Trump presidency.

Immigration Debates Continue

As issues of race and gender captured much public discussion, immigration continued on as a potent political issue. Since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society liberalized immigration laws in the 1960s, the demographics of the United States have been transformed. In 2012, nearly one-quarter of all Americans were immigrants or the sons and daughters of immigrants. Half came from Latin America. The ongoing Hispanicization of the United States and the ever-shrinking proportion of non-Hispanic White people have been the most talked about trends among demographic observers. By 2013, 17 percent of the nation was Hispanic. In 2014, Latinos surpassed non-Latino whites to become the largest ethnic group in California. In Texas, the image of a white cowboy hardly captures the demographics of a minority-majority state in which Hispanic Texans will soon become the largest ethnic group. For the nearly 1.5 million people of Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, for instance, where most residents speak Spanish at home, a full three-fourths of the population is bilingual. Political commentators often wonder what political transformations these populations will bring about when they come of age and begin voting in larger numbers.

Try It

Conclusion: History is Powerful

In 2021, Idaho became the first state to pass a law to ban the teaching of Critical Race Theory (CRT) in public schools. Thirty-five states since followed suit. However, not all legislation contains language specifically targeting CRT broadly. Instead, many of the bills make it illegal for teachers to educate their students on race, gender, and sexual orientation more broadly. For example, On May 24th, 2021 Governor Bill Lee of Tennessee signed into a law that states that “An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously.” Analyzing the ways in which White people are inherently privileged in society is a pillar stone to CRT. Provision 8 states that the following concept is prohibited “[that] this state or the United States is fundamentally or irredeemably racist or sexist.” The problem as defined by the Tennessee lawmakers who created and passed this bill is that students are being exposed to conversations around race too early and that these conversations are divisive.

The commonality between all of the anti-CRT legislation is the idea that students are influenced by how they learn history. More specifically, the inclusion of the histories of Black, Indigenous, and people of color can influence students to feel differently about different groups of people. This is a strong indicator of how powerful history truly is. All over the world throughout history there have been efforts to erase parts of history. Typically, the goal of this is to re-enforce the white-supremacist and Eurocentric view of history. Students all throughout the country are turning to social media to advocate for themselves and their teachers to push against the current legislation.

Try It

Glossary

critical race theory (CRT): an academic theory that states race is a social construct, and that racism is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies

Hispanicization: the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by Hispanic culture

inflation: the rate of increase in prices over a given period of time

political action committee (PAC): pools campaign contributions from members and donates those funds to campaigns for or against candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation

systemic racism: a form of racism that is embedded in the laws and regulations of a society or an organization

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Nicole Winans for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US History. Provided by: The American YAWP. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/30-the-recent-past/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike