Learning Outcomes

- Determine the convergence or divergence of a given sequence

We now turn our attention to one of the most important theorems involving sequences: the Monotone Convergence Theorem. Before stating the theorem, we need to introduce some terminology and motivation. We begin by defining what it means for a sequence to be bounded.

Definition

A sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is bounded above if there exists a real number [latex]M[/latex] such that

for all positive integers [latex]n[/latex].

A sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is bounded below if there exists a real number [latex]M[/latex] such that

for all positive integers [latex]n[/latex].

A sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is a bounded sequence if it is bounded above and bounded below.

If a sequence is not bounded, it is an unbounded sequence.

For example, the sequence [latex]\left\{\frac{1}{n}\right\}[/latex] is bounded above because [latex]\frac{1}{n}\le 1[/latex] for all positive integers [latex]n[/latex]. It is also bounded below because [latex]\frac{1}{n}\ge 0[/latex] for all positive integers n. Therefore, [latex]\left\{\frac{1}{n}\right\}[/latex] is a bounded sequence. On the other hand, consider the sequence [latex]\left\{{2}^{n}\right\}[/latex]. Because [latex]{2}^{n}\ge 2[/latex] for all [latex]n\ge 1[/latex], the sequence is bounded below. However, the sequence is not bounded above. Therefore, [latex]\left\{{2}^{n}\right\}[/latex] is an unbounded sequence.

We now discuss the relationship between boundedness and convergence. Suppose a sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is unbounded. Then it is not bounded above, or not bounded below, or both. In either case, there are terms [latex]{a}_{n}[/latex] that are arbitrarily large in magnitude as [latex]n[/latex] gets larger. As a result, the sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] cannot converge. Therefore, being bounded is a necessary condition for a sequence to converge.

Theorem: Convergent Sequences Are Bounded

If a sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] converges, then it is bounded.

Note that a sequence being bounded is not a sufficient condition for a sequence to converge. For example, the sequence [latex]\left\{{\left(-1\right)}^{n}\right\}[/latex] is bounded, but the sequence diverges because the sequence oscillates between [latex]1[/latex] and [latex]-1[/latex] and never approaches a finite number. We now discuss a sufficient (but not necessary) condition for a bounded sequence to converge.

Consider a bounded sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex]. Suppose the sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is increasing. That is, [latex]{a}_{1}\le {a}_{2}\le {a}_{3}\ldots[/latex]. Since the sequence is increasing, the terms are not oscillating. Therefore, there are two possibilities. The sequence could diverge to infinity, or it could converge. However, since the sequence is bounded, it is bounded above and the sequence cannot diverge to infinity. We conclude that [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] converges. For example, consider the sequence

Since this sequence is increasing and bounded above, it converges. Next, consider the sequence

Even though the sequence is not increasing for all values of [latex]n[/latex], we see that [latex]-\frac{1}{2}<\text{-}\frac{1}{3}<\text{-}\frac{1}{4}<\cdots[/latex]. Therefore, starting with the eighth term, [latex]{a}_{8}=-\frac{1}{2}[/latex], the sequence is increasing. In this case, we say the sequence is eventually increasing. Since the sequence is bounded above, it converges. It is also true that if a sequence is decreasing (or eventually decreasing) and bounded below, it also converges.

Definition

A sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is increasing for all [latex]n\ge {n}_{0}[/latex] if

A sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is decreasing for all [latex]n\ge {n}_{0}[/latex] if

A sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is a monotone sequence for all [latex]n\ge {n}_{0}[/latex] if it is increasing for all [latex]n\ge {n}_{0}[/latex] or decreasing for all [latex]n\ge {n}_{0}[/latex].

We now have the necessary definitions to state the Monotone Convergence Theorem, which gives a sufficient condition for convergence of a sequence.

Theorem: Monotone Convergence Theorem

If [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is a bounded sequence and there exists a positive integer [latex]{n}_{0}[/latex] such that [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is monotone for all [latex]n\ge {n}_{0}[/latex], then [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] converges.

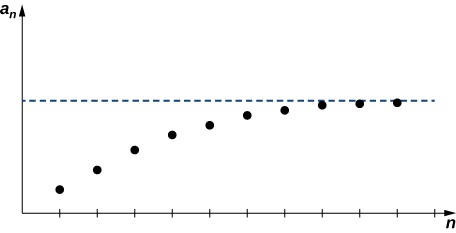

The proof of this theorem is beyond the scope of this text. Instead, we provide a graph to show intuitively why this theorem makes sense (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Since the sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] is increasing and bounded above, it must converge.

In the following example, we show how the Monotone Convergence Theorem can be used to prove convergence of a sequence.

Example: Using the Monotone Convergence Theorem

For each of the following sequences, use the Monotone Convergence Theorem to show the sequence converges and find its limit.

- [latex]\left\{\frac{{4}^{n}}{n\text{!}}\right\}[/latex]

- [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] defined recursively such that

[latex]{a}_{1}=2\text{ and }{a}_{n+1}=\frac{{a}_{n}}{2}+\frac{1}{2{a}_{n}}\text{ for all }n\ge 2[/latex].

try it

Consider the sequence [latex]\left\{{a}_{n}\right\}[/latex] defined recursively such that [latex]{a}_{1}=1[/latex], [latex]{a}_{n}=\frac{{a}_{n - 1}}{2}[/latex]. Use the Monotone Convergence Theorem to show that this sequence converges and find its limit.

Watch the following video to see the worked solution to the above Try IT.

For closed captioning, open the video on its original page by clicking the Youtube logo in the lower right-hand corner of the video display. In YouTube, the video will begin at the same starting point as this clip, but will continue playing until the very end.

You can view the transcript for this segmented clip of “5.1.3” here (opens in new window).

Try It

ACTIVITY: Fibonacci Numbers

The Fibonacci numbers are defined recursively by the sequence [latex]\left\{{F}_{n}\right\}[/latex] where [latex]{F}_{0}=0[/latex], [latex]{F}_{1}=1[/latex] and for [latex]n\ge 2[/latex],

Here we look at properties of the Fibonacci numbers.

- Write out the first twenty Fibonacci numbers.

- Find a closed formula for the Fibonacci sequence by using the following steps.

- Consider the recursively defined sequence [latex]\left\{{x}_{n}\right\}[/latex] where [latex]{x}_{o}=c[/latex] and [latex]{x}_{n+1}=a{x}_{n}[/latex]. Show that this sequence can be described by the closed formula [latex]{x}_{n}=c{a}^{n}[/latex] for all [latex]n\ge 0[/latex].

- Using the result from part a. as motivation, look for a solution of the equation

[latex]{F}_{n}={F}_{n - 1}+{F}_{n - 2}[/latex]

of the form [latex]{F}_{n}=c{\lambda }^{n}[/latex]. Determine what two values for [latex]\lambda[/latex] will allow [latex]{F}_{n}[/latex] to satisfy this equation. - Consider the two solutions from part b.: [latex]{\lambda }_{1}[/latex] and [latex]{\lambda }_{2}[/latex]. Let [latex]{F}_{n}={c}_{1}{\lambda }_{1}{}^{n}+{c}_{2}{\lambda }_{2}{}^{n}[/latex]. Use the initial conditions [latex]{F}_{0}[/latex] and [latex]{F}_{1}[/latex] to determine the values for the constants [latex]{c}_{1}[/latex] and [latex]{c}_{2}[/latex] and write the closed formula [latex]{F}_{n}[/latex].

- Use the answer in 2 c. to show that

[latex]\underset{n\to \infty }{\text{lim}}\frac{{F}_{n+1}}{{F}_{n}}=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}[/latex].

The number [latex]\varphi =\frac{\left(1+\sqrt{5}\right)}{2}[/latex] is known as the golden ratio (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. The seeds in a sunflower exhibit spiral patterns curving to the left and to the right. The number of spirals in each direction is always a Fibonacci number—always. (credit: modification of work by Esdras Calderan, Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 8. The proportion of the golden ratio appears in many famous examples of art and architecture. The ancient Greek temple known as the Parthenon was designed with these proportions, and the ratio appears again in many of the smaller details. (credit: modification of work by TravelingOtter, Flickr)

Candela Citations

- 5.1.3. Authored by: Ryan Melton. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Calculus Volume 2. Authored by: Gilbert Strang, Edwin (Jed) Herman. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/calculus-volume-2/pages/1-introduction. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/calculus-volume-2/pages/1-introduction