Henry Ford did not invent the automobile or the assembly line. Instead, he was the most successful at marrying these two technologies together in ways that increased efficiency and reduced costs. Small household goods were manufactured on assembly lines and canned meats were made by stripping meat from carcasses on “disassembly” lines. Prior to the early 1900s, automobile chassis were placed on blocks, and workers brought the parts to the cars to be assembled one at a time. In 1901, Ransom E. Olds of Lansing had shown that the assembly line could be made to work for automotive production, despite the size and weight of the product. However, the Oldsmobile factory burned to the ground, and Henry Ford invested in a much larger factory that built upon Olds’ methods. Ford’s heavy steel rails and conveyer belts moved a car’s chassis down a line. As a result, workers could stand in one place and complete one simple task, such as securing a specific bolt or adding a headlamp as cars moved along the line.

Ford’s newest assembly line, complete with its massive moving belts, was up and running in 1913. Ford produced 250,000 Model T automobiles that year. This was thirty times as many cars as Ford had produced a few years prior; it was also more cars than Oldsmobile and over eighty other competing automakers based primarily out of Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois had ever made. A decade later, Ford was producing 2 million Model Ts, which were nearly identical to the earlier models except for the price. Ford was able to take advantage of economies of scale through mass production; consequently, the price of the Model T dropped from over $800 to under $300. Other automakers produced more diverse offerings, and many competing automakers produced better or cheaper cars. However, in 1913, no one could match the quality of the Model T for the price Ford was charging. As for the monotony of mass production, Ford quipped that his customers could have his vehicle in any color they chose so long as that color was black.

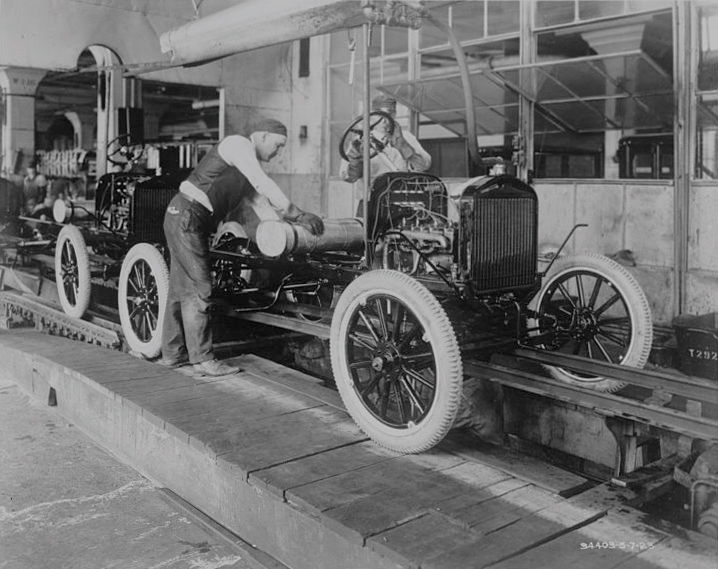

Figure 6.5

Ford automobiles being produced on a Detroit assembly line in 1923.

The work was routine and could be completed by anyone with minimal training. As a result, Ford no longer needed to hire workers with mechanical expertise. Instead, he hired unskilled workers but offered better wages than they might make on other assembly lines. Ford famously introduced the Five Dollar Plan, a daily wage that was roughly double the $2–$3 pay rate that was typical for factory work. Ford employees were required to submit to investigations by Ford’s Social Department. Ford desired only sober workers who shunned cigarettes and fast lifestyles. By the mid-1920s, the investigators no longer made home visits to determine whether factory workers drank alcohol or engaged in other behaviors their paternalistic boss considered a vice. Instead, they were more likely to investigate a worker’s political beliefs. Anyone who embraced Socialism or even considered starting a union would be terminated.

The high wages Ford workers earned permitted most employees to purchase their own automobile. These workers were required to make that purchase a Ford automobile or else they would share the fate of those who attempted to start a union in a Ford plant. Given the high wages Ford offered, most workers tolerated Ford’s demands and shunned unionization as Socialistic or even un-American. Ford himself wrapped his techniques of mass production, low prices, and high wages in the language of Americana. The 23 million automobiles on the road in 1929 satisfied Ford that he had democratized the automobile by bringing car ownership to the masses.

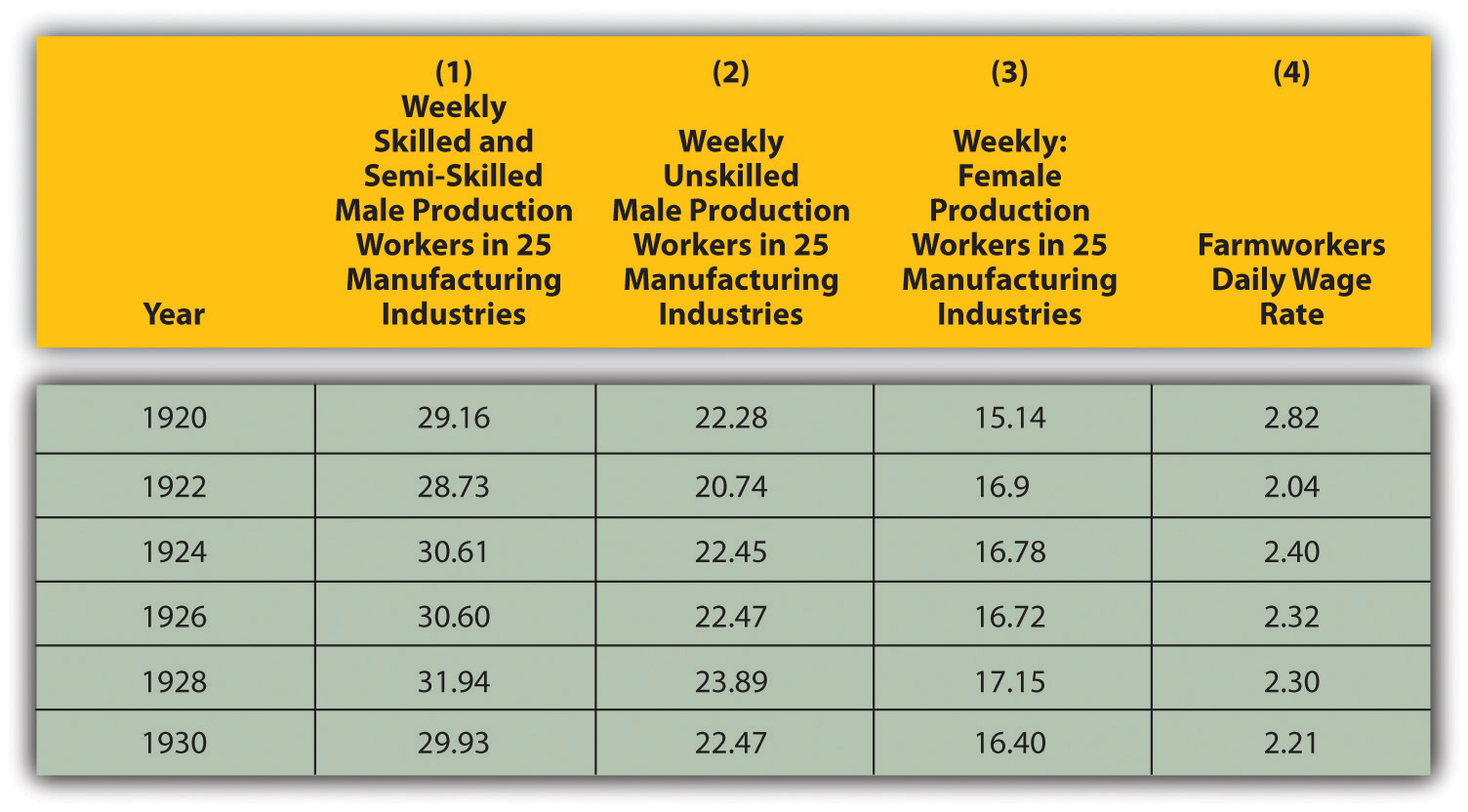

Ford’s assembly line methods were studied by the emerging business colleges and perfected to maximize efficiency of movement. Older methods of production that required skilled craftsmen largely disappeared, as did the level of job satisfaction workers expressed once they no longer felt connected to the products they produced. Instead of seeing a finished product or working closely with a team, workers stood in one place and performed repetitive tasks. The system was tremendously efficient, and it did provide the opportunity for more jobs among non-skilled workers. Worker productivity in most industrial fields increased by about 50 percent while real wages for the average factory worker also increased. However, these wages usually grew by no more than 10 percent over the decade. The average workweek declined to just over forty hours in some fields—a long goal of the labor movement. However, the typical workweek for industrial workers remained six days of forty-eight hours of labor. In addition, upward mobility was hindered by the elimination of most skilled positions, and a new generation of factory worker was even more disconnected from his labor than in the past.

Figure 6.6 Real Average Weekly or Daily Earnings for Selected Occupations, 1920–1930

Previous generations of farmers and craftsmen had been able to see tangible evidence of their labor. The only workers in factories with assembly lines who even saw the finished product were those who worked on loading docks, and they usually did not participate in the production of goods. Factory work had always featured monotony, a contest between one’s will and the time clock. But workers could at least identify the products they had made before the adoption of the assembly line. Consequently, workers no longer identified themselves in terms of their jobs, as farmers and craftsmen had in the past. No celebration of the harvest took place; no trade or skill provided a sense of identity and union. Unskilled workers were much more likely to change employers and industries many times throughout their lives. As a result, the urban worker sought satisfaction and meaning outside of their jobs in ways that led to the proliferation of recreational activities and the celebration of consumption rather than production.

Candela Citations

- section of text from Chapter 6.1 Prosperity and Its Limits, includes images 6.5 and 6.6. Located at: https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/united-states-history-volume-2/s09-01-prosperity-and-its-limits.html. Project: U.S. History Vol. 2. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- image of Henry Ford. Authored by: Hartsook. Provided by: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Ford#/media/File:Henry_ford_1919.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright