27.2.6: Japan’s Industrial Revolution

The rapid industrialization of Japan during the Meiji period resulted from a carefully engineered transfer of Western technology, modernization trends, and education led by the government in partnership with the private sector.

Learning Objective

Analyze the success of Japan’s rapid shift to industrialization

Key Points

- The Industrial Revolution in Japan began about 1870 as Meiji period leaders decided to catch up with the West. In 1871, a group of Japanese statesmen and scholars known as the Iwakura Mission embarked upon a voyage across Europe and the United States. The mission aimed to gain recognition for the newly reinstated imperial dynasty and begin preliminary renegotiation of the unequal treaties, but it was the exploration of modern Western industrial, political, military, and educational systems and structures that became its most consequential outcome.

- Japan’s Industrial Revolution first appeared in textiles, including cotton and especially silk, traditionally made in home workshops in rural areas. By the 1890s, Japanese textiles dominated the home markets and competed successfully with British products in China and India. Japan largely skipped water power and moved straight to steam-powered mills, which were more productive. That in turn created a demand for coal.

- To promote industrialization, the government decided that while it should help private business allocate resources and plan, the private sector was best equipped to stimulate economic growth. In the early Meiji period, the government built factories and shipyards that were sold to entrepreneurs at a fraction of their value. It also provided infrastructure, building railroads, improving roads, and inaugurating a land reform program to prepare the country for further development.

- Important social changes supported by the government also fueled industrialization. One of the biggest economic impacts of the Meiji period was the end of the feudal system. Japanese people now had the ability to become more educated as the Meiji period leaders inaugurated a new, more accessible Western-based education system.

- The government initially was involved in economic modernization, but by the 1890s largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process. Hand in hand, industrial and financial business conglomerates known as zaibatsu and government guided the nation, borrowing technology from the West. The private sector embraced the government-promoted Western model of capitalism.

- The phenomenal industrial growth sparked rapid urbanization, and most people lived longer and healthier lives. Like in other rapidly industrializing countries, poor working conditions in factories led to growing labor unrest, and many workers and intellectuals came to embrace socialist ideas. The government also introduced social legislation in 1911, setting maximum work hours and a minimum age for employment.

Key Terms

- Iwakura Mission

- A Japanese diplomatic voyage to the United States and Europe conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. Although it had a number of political, diplomatic, and economic goals, it is most well-known and possibly most significant in terms of its impact on the modernization of Japan after a long period of isolation from the West.

- zaibatsu

- Industrial and financial business conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over significant parts of the Japanese economy from the Meiji period until the end of World War II.

Iwakura Mission

The Industrial Revolution in Japan began about 1870 as Meiji period leaders decided to catch up with the West. In 1871, a group of Japanese statesmen and scholars known as the Iwakura Mission embarked upon a voyage across Europe and the United States. The aim of the mission was threefold: to gain recognition for the newly reinstated imperial dynasty under the Emperor Meiji, to begin preliminary renegotiation of the unequal treaties with the dominant world powers, and to explore modern Western industrial, political, military, and educational systems and structures.

The mission was named after and headed by Iwakura Tomomi in the role of extraordinary and plenipotentiary ambassador, assisted by four vice-ambassadors. It also included a number of administrators and scholars, totaling 48 people. In addition to the mission staff, about 53 students and attendants joined. Several students were left behind to complete their education in the foreign countries, including five young women who stayed in the United States.

Leaders of the Iwakura Mission photographed in London in 1872: Kido Takayoshi, Yamaguchi Masuka, Iwakura Tomomi, Itō Hirobumi, Ōkubo Toshimichi

The mission is the most well-known and possibly most significant in terms of its impact on the modernization of Japan after a long period of isolation from the West. It was first proposed by the influential Dutch missionary and engineer Guido Verbeck, based to some degree on the model of the Grand Embassy of Peter I.

Of the initial goals of the mission, the aim of revision of the unequal treaties was not achieved, prolonging the mission by almost four months but also impressing the importance of the second goal on its members. The attempts to negotiate new treaties under better conditions with the foreign governments led to criticism that members of the mission were attempting to go beyond the mandate set by the Japanese government. The missionaries were nonetheless impressed by industrial modernization in America and Europe and the tour provided them with a strong impetus to lead similar modernization initiatives.

Industrialization in Japan

Japan’s Industrial Revolution first appeared in textiles, including cotton and especially silk, traditionally made in home workshops in rural areas. By the 1890s, Japanese textiles dominated the home markets and competed successfully with British products in China and India. Japanese shippers competed with European traders to carry these goods across Asia and even in Europe. As in the West, the textile mills employed mainly women, half of them younger than age 20. They were sent by and gave their wages to their fathers. Japan largely skipped water power and moved straight to steam-powered mills, which were more productive. That in turn created a demand for coal.

To promote industrialization, the government decided that while it should help private business to allocate resources and to plan, the private sector was best equipped to stimulate economic growth. The greatest role of government was to help provide the economic conditions in which business could flourish. In the early Meiji period, the government built factories and shipyards that were sold to entrepreneurs at a fraction of their values. Many of these businesses grew rapidly into larger conglomerates. Government emerged as chief promoter of private enterprise, enacting a series of pro-business policies. The government also provided infrastructure, building railroads, improving roads, and inaugurating a land reform program to prepare the country for further development.

Social Changes

Important social changes supported by the government also fueled industrialization. One of the biggest economic impacts of the period was the end of the feudal system. With a relatively loose social structure, the Japanese were able to advance through the ranks of society more easily than before by inventing and selling their own wares. The Japanese people also now had the ability to become more educated. The Meiji period leaders inaugurated a new Western-based education system for all young people, sent thousands of students to the United States and Europe, and hired more than 3,000 Westerners to teach modern science, mathematics, technology, and foreign languages in Japan. With a more educated population, Japan’s industrial sector grew significantly.

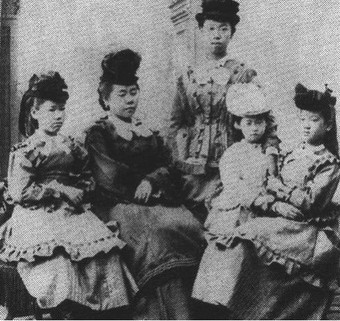

The first Japanese study-abroad female students to the United States, sponsored by the Meiji Government. From left: Shigeko Nagai (age 10), Teiko Ueda (16), Ryōko Yoshimasu (16), Umeko Tsuda (1864–1929, age 9 in the picture), and Sutematsu Yamakawa (1860–1919, age 12 in the picture).

Tsuda Umeko, who left Japan to study in the US at the age of 7, returned to Japan in 1900 and founded Tsuda College. It remains one of the most prestigious women’s institutes of higher education in Japan. Although Tsuda strongly desired social reform for women, she did not advocate feminist values and opposed the women’s suffrage movement. Her activities were based on her philosophy that education should focus on developing individual intelligence and personality.

Government vs. Private Sector

The government initially was involved in economic modernization, providing a number of “model factories” to facilitate the transition to the modern period. Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. Establishment of a modern institutional framework conducive to an advanced capitalist economy took time, but was completed by the 1890s. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons.

From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. The private sector—in a nation with an abundance of aggressive entrepreneurs—welcomed such change. Hand in hand, industrial and financial business conglomerates known as zaibatsu and government guided the nation, borrowing technology from the West. Many of the former feudal lords, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries. Those who had been informally involved in foreign trade before the Meiji Restoration also flourished. Old firms that clung to their traditional ways failed in the new business environment.

After the first twenty years of the Meiji period, the industrial economy expanded rapidly with inputs of advanced Western technology and large private investments. Implementing the Western ideal of capitalism into the development of technology and applying it to their military helped make Japan into both a militaristic and economic powerhouse by the beginning of the 20th century. Stimulated by wars and through cautious economic planning, Japan emerged from World War I as a major industrial nation. Japan gradually took control of much of Asia’s market for manufactured goods. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products—a reflection of Japan’s relative poverty in raw materials.

Consequences

The phenomenal industrial growth sparked rapid urbanization. The proportion of the population working in agriculture shrank from 75 percent in 1872 to 50 percent by 1920. Japan enjoyed solid economic growth during the Meiji period and most people lived longer and healthier lives. The population rose from 34 million in 1872 to 52 million in 1915. Like in other rapidly industrializing countries, poor working conditions in factories led to growing labor unrest, and many workers and intellectuals came to embrace socialist ideas. The Meiji government responded with harsh suppression of dissent. Radical socialists plotted to assassinate the Emperor in the High Treason Incident of 1910, after which the Tokkō secret police force was established to root out left-wing agitators. The government also introduced social legislation in 1911, setting maximum work hours and a minimum age for employment.

Attributions

- Japan’s Industrial Revolution

-

“Economic history of Japan.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_history_of_Japan. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Iwakura_mission.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iwakura_mission.jpg. Wikimedia Commons Public domain.

-

“First_female_study-abroad_students.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_female_study-abroad_students.jpg. Wikimedia Commons Public domain.

Candela Citations

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/. License: CC BY: Attribution