Learning Objectives

- Define and discuss happiness, including its determinants and how to increase it

Although the study of stress and how it affects us physically and psychologically is fascinating, it is—admittedly—somewhat of a grim topic. Psychology is also interested in the study of a more upbeat and encouraging approach to human affairs—the quest for happiness.

Happiness

America’s founders declared that its citizens have an unalienable right to pursue happiness. But what is happiness? When asked to define the term, people emphasize different aspects of this elusive state. Indeed, happiness is somewhat ambiguous and can be defined from different perspectives (Martin, 2012). Some people, especially those who are highly committed to their religious faith, view happiness in ways that emphasize virtuosity, reverence, and enlightened spirituality. Others see happiness as primarily contentment—the inner peace and joy that come from deep satisfaction with one’s surroundings, relationships with others, accomplishments, and oneself. Still others view happiness mainly as pleasurable engagement with their personal environment—having a career and hobbies that are engaging, meaningful, rewarding, and exciting. These differences, of course, are merely differences in emphasis. Most people would probably agree that each of these views, in some respects, captures the essence of happiness.

Elements of Happiness

Some psychologists have suggested that happiness consists of three distinct elements: the pleasant life, the good life, and the meaningful life, as shown in Figure 1 (Seligman, 2002; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). The pleasant life is realized through the attainment of day-to-day pleasures that add fun, joy, and excitement to our lives. For example, evening walks along the beach and a fulfilling sex life can enhance our daily pleasure and contribute to the pleasant life. The good life is achieved through identifying our unique skills and abilities and engaging these talents to enrich our lives; those who achieve the good life often find themselves absorbed in their work or their recreational pursuits. The meaningful life involves a deep sense of fulfillment that comes from using our talents in the service of the greater good: in ways that benefit the lives of others or that make the world a better place. In general, the happiest people tend to be those who pursue the full life—they orient their pursuits toward all three elements (Seligman et al., 2005).

Figure 1. Happiness is an enduring state of well-being involving satisfaction in the pleasant, good, and meaningful aspects of life.

For practical purposes, a precise definition of happiness might incorporate each of these elements: an enduring state of mind consisting of joy, contentment, and other positive emotions, plus the sense that one’s life has meaning and value (Lyubomirsky, 2001). The definition implies that happiness is a long-term state—what is often characterized as subjective well-being—rather than merely a transient positive mood we all experience from time to time. It is this enduring happiness that has captured the interests of psychologists and other social scientists.

The study of happiness has grown dramatically in the last three decades (Diener, 2013). One of the most basic questions that happiness investigators routinely examine is this: How happy are people in general? The average person in the world tends to be relatively happy and tends to indicate experiencing more positive feelings than negative feelings (Diener, Ng, Harter, & Arora, 2010). When asked to evaluate their current lives on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 (with 0 representing “worst possible life” and 10 representing “best possible life”), people in more than 150 countries surveyed from 2010–2012 reported an average score of 5.2. People who live in North America, Australia, and New Zealand reported the highest average score at 7.1, whereas those living Sub-Saharan Africa reported the lowest average score at 4.6 (Helliwell, Layard, & Sachs, 2013). Worldwide, the five happiest countries are Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Sweden; the United States is ranked 17th happiest (Figure 2) (Helliwell et al., 2013).

Figure 2. (a) Surveys of residents in over 150 countries indicate that Denmark has the happiest citizens in the world. (b) Americans ranked the United States as the 17th happiest country in which to live. (credit a: modification of work by “JamesZ_Flickr”/Flickr; credit b: modification of work by Ryan Swindell)

Several years ago, a Gallup survey of more than 1,000 U.S. adults found that 52% reported that they were “very happy.” In addition, more than 8 in 10 indicated that they were “very satisfied” with their lives (Carroll, 2007). However, a recent poll found that only 42% of American adults report being “very happy.” The groups that show the greatest declines in happiness are people of color, those who have not completed a college education, and those who politically identify as Democrats or independents (McCarthy, 2020). These results suggest that challenging economic conditions may be related to declines in happiness. Of course, this interpretation implies that happiness is closely tied to one’s finances. But, is it? What factors influence happiness?

Subjective Well-Being

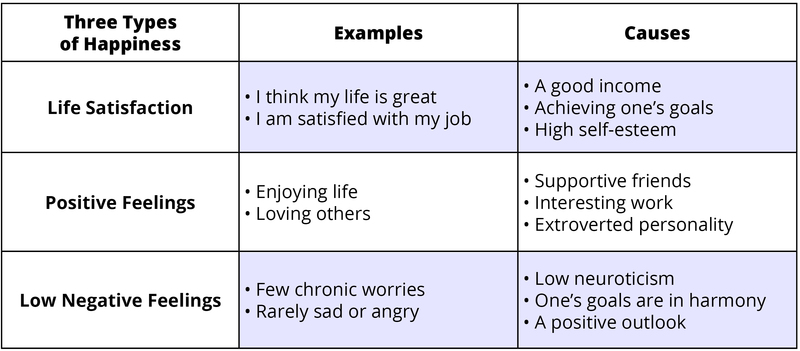

Another way that researchers define happiness is by examining high life satisfaction, frequent positive feelings, and infrequent negative feelings (Diener, 1984). “Subjective well-being” is the label given by scientists to the various forms of happiness taken together. Although there are additional forms of SWB, the three in the table below have been studied extensively. The table also shows that the causes of the different types of happiness can be somewhat different.

Table 1. Three Types of Subjective Well-Being

You can see in the table that there are different causes of happiness, and that these causes are not identical for the various types of SWB. Therefore, there is no single key, no magic wand—high SWB is achieved by combining several different important elements (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008). Thus, people who promise to know the key to happiness are oversimplifying.

Factors Connected to Happiness

What really makes people happy? What factors contribute to sustained joy and contentment? Is it money, attractiveness, material possessions, a rewarding occupation, a satisfying relationship? Extensive research over the years has examined this question. One finding is that age is related to happiness: Life satisfaction usually increases the older people get, but there do not appear to be gender differences in happiness (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999). Although it is important to point out that much of this work has been correlational, many of the key findings (some of which may surprise you) are summarized below.

Family and other social relationships appear to be key factors correlated with happiness. Studies show that married people report being happier than those who are single, divorced, or widowed (Diener et al., 1999). Happy individuals also report that their marriages are fulfilling (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). In fact, some have suggested that satisfaction with marriage and family life is the strongest predictor of happiness (Myers, 2000). Happy people tend to have more friends, more high-quality social relationships, and stronger social support networks than less happy people (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Happy people also have a high frequency of contact with friends (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000).

Can money buy happiness? In general, extensive research suggests that the answer is yes, but with several caveats. While a nation’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) is associated with happiness levels (Helliwell et al., 2013), changes in GDP (which is a less certain index of household income) bear little relationship to changes in happiness (Diener, Tay, & Oishi, 2013). On the whole, residents of affluent countries tend to be happier than residents of poor countries; within countries, wealthy individuals are happier than poor individuals, but the association is much weaker (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002). To the extent that it leads to increases in purchasing power, increases in income are associated with increases in happiness (Diener, Oishi, & Ryan, 2013). However, income within societies appears to correlate with happiness only up to a point. In a study of over 450,000 U.S. residents surveyed by the Gallup Organization, Kahneman and Deaton (2010) found that well-being rises with annual income, but only up to $75,000. The average increase in reported well-being for people with incomes greater than $75,000 was null. As implausible as these findings might seem—after all, higher incomes would enable people to indulge in Hawaiian vacations, prime seats as sporting events, expensive automobiles, and expansive new homes—higher incomes may impair people’s ability to savor and enjoy the small pleasures of life (Kahneman, 2011). Indeed, researchers in one study found that participants exposed to a subliminal reminder of wealth spent less time savoring a chocolate candy bar and exhibited less enjoyment of this experience than did participants who were not reminded of wealth (Quoidbach, Dunn, Petrides, & Mikolajczak, 2010).

What about education and employment? Happy people, compared to those who are less happy, are more likely to graduate from college and secure more meaningful and engaging jobs. Once they obtain a job, they are also more likely to succeed (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). While education shows a positive (but weak) correlation with happiness, intelligence is not appreciably related to happiness (Diener et al., 1999).

Does religiosity correlate with happiness? In general, the answer is yes (Hackney & Sanders, 2003). However, the relationship between religiosity and happiness depends on societal circumstances. Nations and states with more difficult living conditions (e.g., widespread hunger and low life expectancy) tend to be more highly religious than societies with more favorable living conditions. Among those who live in nations with difficult living conditions, religiosity is associated with greater well-being; in nations with more favorable living conditions, religious and nonreligious individuals report similar levels of well-being (Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011).

Clearly the living conditions of one’s nation can influence factors related to happiness. What about the influence of one’s culture? To the extent that people possess characteristics that are highly valued by their culture, they tend to be happier (Diener, 2012). For example, self-esteem is a stronger predictor of life satisfaction in individualistic cultures than in collectivistic cultures (Diener, Diener, & Diener, 1995), and extraverted people tend to be happier in extraverted cultures than in introverted cultures (Fulmer et al., 2010).

So we’ve identified many factors that exhibit some correlation to happiness. What factors don’t show a correlation? Researchers have studied both parenthood and physical attractiveness as potential contributors to happiness, but no link has been identified. Although people tend to believe that parenthood is central to a meaningful and fulfilling life, aggregate findings from a range of countries indicate that people who do not have children are generally happier than those who do (Hansen, 2012). And although one’s perceived level of attractiveness seems to predict happiness, a person’s objective physical attractiveness is only weakly correlated with her happiness (Diener, Wolsic, & Fujita, 1995).

Try It

Life Events and Happiness

An important point should be considered regarding happiness. People are often poor at affective forecasting: predicting the intensity and duration of their future emotions (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). In one study, nearly all newlywed spouses predicted their marital satisfaction would remain stable or improve over the following four years; despite this high level of initial optimism, their marital satisfaction actually declined during this period (Lavner, Karner, & Bradbury, 2013). In addition, we are often incorrect when estimating how our long-term happiness would change for the better or worse in response to certain life events. For example, it is easy for many of us to imagine how euphoric we would feel if we won the lottery, were asked on a date by an attractive celebrity, or were offered our dream job. It is also easy to understand how long-suffering fans of the Chicago Cubs baseball team, which has not won a World Series championship since 1908, think they would feel permanently elated if their team would finally win another World Series. Likewise, it is easy to predict that we would feel permanently miserable if we suffered a crippling accident or if a romantic relationship ended.

However, something similar to sensory adaptation often occurs when people experience emotional reactions to life events. In much the same way our senses adapt to changes in stimulation (e.g., our eyes adapting to bright light after walking out of the darkness of a movie theater into the bright afternoon sun), we eventually adapt to changing emotional circumstances in our lives (Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Helson, 1964). When an event that provokes positive or negative emotions occurs, at first we tend to experience its emotional impact at full intensity. We feel a burst of pleasure following such things as a marriage proposal, birth of a child, acceptance to law school, an inheritance, and the like; as you might imagine, lottery winners experience a surge of happiness after hitting the jackpot (Lutter, 2007). Likewise, we experience a surge of misery following widowhood, a divorce, or a layoff from work. In the long run, however, we eventually adjust to the emotional new normal; the emotional impact of the event tends to erode, and we eventually revert to our original baseline happiness levels. Thus, what was at first a thrilling lottery windfall or World Series championship eventually loses its luster and becomes the status quo (Figure 3). Indeed, dramatic life events have much less long-lasting impact on happiness than might be expected (Brickman, Coats, & Janoff-Bulman, 1978).

Figure 3. (a) Long-suffering Chicago Cub fans felt elated in 2016 when their team won a World Series championship, a feat that had not been accomplished by that franchise in over a century. (b) In ways that are similar, those who play the lottery rightfully think that choosing the correct numbers and winning millions would lead to a surge in happiness. However, the initial burst of elation following such elusive events would most likely erode with time. (credit a: modification of work by Phil Roeder; credit b: modification of work by Robert S. Donovan)

Dig Deeper: MEasuring Happiness

An example of adaptation to circumstances is shown in Figure 4, which shows the daily moods of “Harry,” a college student who had Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a form of cancer). As can be seen, over the 6-week period when I studied Harry’s moods, they went up and down. A few times his moods dropped into the negative zone below the horizontal blue line. Most of the time Harry’s moods were in the positive zone above the line. But about halfway through the study Harry was told that his cancer was in remission—effectively cured—and his moods on that day spiked way up. But notice that he quickly adapted—the effects of the good news wore off, and Harry adapted back toward where he was before. So even the very best news one can imagine—recovering from cancer—was not enough to give Harry a permanent “high.” Notice too, however, that Harry’s moods averaged a bit higher after cancer remission. Thus, the typical pattern is a strong response to the event, and then a dampening of this joy over time. However, even in the long run, the person might be a bit happier or unhappier than before.

Recently, some have raised questions concerning the extent to which important life events can permanently alter people’s happiness set points (Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006). Evidence from a number of investigations suggests that, in some circumstances, happiness levels do not revert to their original positions. For example, although people generally tend to adapt to marriage so that it no longer makes them happier or unhappier than before, they often do not fully adapt to unemployment or severe disabilities (Diener, 2012). Figure 5, which is based on longitudinal data from a sample of over 3,000 German respondents, shows life satisfaction scores several years before, during, and after various life events, and it illustrates how people adapt (or fail to adapt) to these events. German respondents did not get lasting emotional boosts from marriage; instead, they reported brief increases in happiness, followed by quick adaptation. In contrast, widows and those who had been laid off experienced sizeable decreases in happiness that appeared to result in long-term changes in life satisfaction (Diener et al., 2006). Further, longitudinal data from the same sample showed that happiness levels changed significantly over time for nearly a quarter of respondents, with 9% showing major changes (Fujita & Diener, 2005). Thus, long-term happiness levels can and do change for some people.

Increasing Happiness

Some recent findings about happiness provide an optimistic picture, suggesting that real changes in happiness are possible. For example, thoughtfully developed well-being interventions designed to augment people’s baseline levels of happiness may increase happiness in ways that are permanent and long-lasting, not just temporary. These changes in happiness may be targeted at individual, organizational, and societal levels (Diener et al., 2006). Researchers in one study found that a series of happiness interventions involving such exercises as writing down three good things that occurred each day led to increases in happiness that lasted over six months (Seligman et al., 2005).

Measuring happiness and well-being at the societal level over time may assist policy makers in determining if people are generally happy or miserable, as well as when and why they might feel the way they do. Studies show that average national happiness scores (over time and across countries) relate strongly to six key variables: per capita gross domestic product (GDP, which reflects a nation’s economic standard of living), social support, freedom to make important life choices, healthy life expectancy, freedom from perceived corruption in government and business, and generosity (Helliwell et al., 2013). Investigating why people are happy or unhappy might help policymakers develop programs that increase happiness and well-being within a society (Diener et al., 2006). Resolutions about contemporary political and social issues that are frequent topics of debate—such as poverty, taxation, affordable health care and housing, clean air and water, and income inequality—might be best considered with people’s happiness in mind.

Try It

Glossary

Candela Citations

- The Pursuit of Happiness. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/14-5-the-pursuit-of-happiness. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being, sections on SWB and Harry example. Authored by: Edward Diener. Provided by: University of Utah, University of Virginia. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/textbooks/wendy-king-introduction-to-psychology-the-full-noba-collection/modules/happiness-the-science-of-subjective-well-being. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike