Learning Objectives

- Describe the daily life of a Civil War soldier

- Explain the role disease played amongst the Union and Confederate armies

Daily Life of a Soldier

Military life consisted of relative monotony punctuated by brief periods of horror. Daily life for a Civil War soldier was one of routine. A typical day began around six in the morning and involved drill, marching, lunch break, and more drilling followed by policing the camp. Weapon inspection and cleaning followed, perhaps one final drill, dinner, and taps around nine or nine thirty in the evening. Soldiers in both armies grew weary of the routine. Picketing or foraging afforded welcome distractions to the monotony.

Soldiers devised clever ways of dealing with the boredom of camp life. The most common was writing. These were highly literate armies; nine out of every ten Federals and eight out of every ten Confederates could read and write. Letters home served as a tether linking soldiers to their loved ones. Soldiers also read, and newspapers were in high demand. News of battles, events in Europe, politics in Washington and Richmond, and local concerns were voraciously sought and traded within the army camps.

Sometimes items were even exchanged between camps from each side. Neither side could consistently provide supplies for their soldiers, so it was not uncommon, though officially forbidden, for common soldiers to trade with the enemy. Confederate soldiers prized northern newspapers and coffee. Northerners were glad to barter these for southern tobacco.

Figure 1. Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery B, Petersburg, Virginia. Photograph by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, 1864. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

While there were nurses, camp followers, and some women who disguised themselves as men, camp life was overwhelmingly male. Soldiers drank liquor, smoked tobacco, gambled money, and swore often. Social commentators feared that when these men returned home, with their hard-drinking and irreligious ways, all decency, faith, and temperance would depart. But not all methods of distraction were detrimental. Soldiers also organized debate societies, composed music, sang songs, wrestled, raced horses, boxed, and played sports.

Music was popular among the soldiers of both armies, creating a diversion from the boredom and atrocities of the war. As a result, soldiers often sang on fatigue duty and while in camp. Favorite songs often reminded the soldiers of home, including “Lorena,” “Home, Sweet Home,” and “Just Before the Battle, Mother.” Dances held in camp offered another way to enjoy music. Since there were often few women nearby, soldiers would dance with one another.

When the Civil War broke out, one of the most popular songs among soldiers and civilians was “John Brown’s Body,” which began “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave.” Started as a Union anthem praising John Brown’s actions at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, then used by Confederates to vilify Brown, both sides’ version of the song stressed that they were on the right side. Eventually the words to Julia Ward Howe’s poem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” were set to the melody, further implying Union success. The themes of popular songs changed over the course of the war, as feelings of inevitable success alternated with feelings of terror and despair.

“dear folks”

Most of what we know about what life was like for soldiers of the Civil War comes from their own words. For example, read this letter back home from Confederate solider, Private Alexander Hunter.

Sunday Sept. 21, 1862

“Dear Folks,

On the 8th we struck up the refrain of “Maryland, My Maryland!” and camped in an apple orchard. We went hungry, for six days not a morsel of bread or meat had gone in our stomachs – and our menu consisted of apple; and corn. We toasted, we burned, we stewed, we boiled, we roasted these two together, and singly, until there was not a man whose form had not caved in, and who had not a bad attack of diarrhea. Our under-clothes were foul and hanging in strips, our socks worn out, and half of the men were bare-footed, many were lame and were sent to the rear; others, of sterner stuff, hobbled along and managed to keep up, while gangs from every company went off in the surrounding country looking for food. . . Many became ill from exposure and starvation, and were left on the road. The ambulances were full, and the whole route was marked with a sick, lame, limping lot, that straggled to the farm- houses that lined the way, and who, in all cases, succored and cared for them. . .

In an hour after the passage of the Potomac the command continued the march through the rich fields of Maryland. The country people lined the roads, gazing in open-eyed wonder upon the long lines of infantry . . .and as far as the eye could reach, was the glitter of the swaying points of the bayonets. It was the first ragged Rebels they had ever seen, and though they did not act either as friends or foes, still they gave liberally, and every haversack was full that day at least. No houses were entered – no damage was done, and the farmers in the vicinity must have drawn a long breath as they saw how safe their property was in the very midst of the army.”

Pvt. Alexander Hunter, Company A, 17th Virginia Infantry[1]

Rampant Disease

One ghastly, often fatal aspect of soldier life was sickness, as the close proximity of thousands of men bred disease. Severe illness haunted both armies, and accounted for over half of all Civil War casualties. Sometimes as many as half of the men in a company could be sick. The overwhelming majority of Civil War soldiers came from rural areas, where less exposure to diseases meant soldiers lacked immunities. Vaccines for diseases such as smallpox were largely unavailable to those outside cities or towns. Despite the common nineteenth-century tendency to see city men as weak or soft, soldiers from urban environments tended to succumb to fewer diseases than their rural counterparts. Poor sanitation and the constant presence of lice contributed to the contagions. Tuberculosis, measles, rheumatism, typhoid, malaria, and smallpox spread almost unchecked among the armies.

Civil War medicine focused almost exclusively on curing the patient rather than preventing disease. Many soldiers attempted to cure themselves by concocting elixirs and medicines themselves. These ineffective home remedies were often made from various plants the men found in woods or fields. There was no understanding of germ theory, so many soldiers did things that we would consider unsanitary today. They ate food that was improperly cooked and handled, and they practiced what we would consider poor personal hygiene. They did not take appropriate steps to ensure that drinking water was free from bacteria. Diarrhea and dysentery were common. These diseases were especially dangerous, as Civil War soldiers did not understand the value of replacing fluids as they were lost. As such, men affected by these conditions would weaken and become unable to fight or march, and as they became dehydrated their immune system became less effective, inviting other infections to attack the body. Through trial and error, soldiers began to protect themselves from some of the more preventable sources of infection. Around 1862 both armies began to dig latrines rather than rely on the local waterways. Burying human and animal waste also cut down on exposure to diseases considerably.

Medical surgery was limited and brutal. If a soldier was wounded in the torso, throat, or head, there was little surgeons could do. Invasive procedures to repair damaged organs or stem blood loss invariably resulted in death. Luckily for soldiers, only approximately one in six combat wounds were to one of those parts. The remaining were to limbs, which was treatable by amputation. Soldiers had the highest chance of survival if the limb was removed within forty-eight hours of injury. A skilled surgeon could amputate a limb in three to five minutes from start to finish. While the lack of germ theory again caused several unsafe practices, such as using the same tools on multiple patients, wiping hands on filthy gowns, or placing hands in communal buckets of water, there is evidence that amputation offered the best chance of survival.

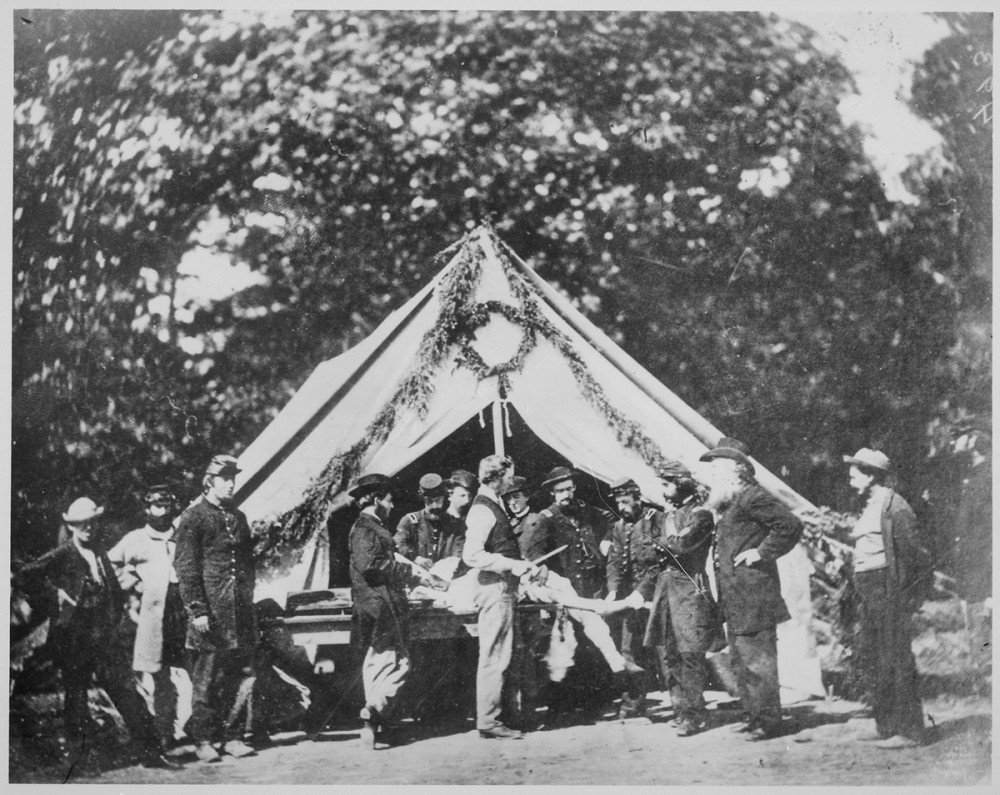

Figure 2. Amputations were a common form of treatment during the war. While it saved the lives of some soldiers, it was extremely painful and resulted in death in many cases. It also produced the first community of war veterans without limbs in American history.

It is a common misconception that amputation was done without anesthesia and against a patient’s wishes. Since the 1830s, Americans understood the benefits of nitrous oxide and ether in easing pain. Chloroform and opium were also used to either render patients unconscious or dull pain during the procedure. Also, surgeons would not amputate without the patient’s consent.

In the Union army alone, 2.8 million ounces of opium liquid and over 5.2 million opium pills were administered. In 1862, William Alexander Hammon was appointed Surgeon General for the United States. He sought to regulate dosages and manage supplies of available medicines, both to prevent overdosing and to ensure that an ample supply remained for the next engagement. However, his guidelines tended to apply only to the regular federal army. Most Union soldiers were in volunteer units and organized at the state level. Their surgeons often ignored posted limits on medicines, or worse, experimented with their own concoctions made from local flora.

In the North, the conditions in hospitals were somewhat superior. This was partly due to the organizational skills of women like Dorothea Dix, who was the Union’s Superintendent for Army Nurses. Additionally, many women were members of the United States Sanitary Commission and helped to staff and supply hospitals in the North. Women took on key roles within hospitals in both North and South. The publisher’s notice for Nurse and Spy in the Union Army stated, “In the opinion of many, it is the privilege of woman to minister to the sick and soothe the sorrowing—and in the present crisis of our country’s history, to aid our brothers to the extent of her capacity.”[2] Mary Chesnut wrote, “Every woman in the house is ready to rush into the Florence Nightingale business.”[3] However, she indicated that after she visited the hospital, “I can never again shut out of view the sights that I saw there of human misery. I sit thinking, shut my eyes, and see it all.”[4] Hospital conditions were often so bad that many volunteer nurses quit soon after beginning.

TRY IT

- “Antietam: Letters and Diaries of Soldiers and Civilians.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed August 25, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/education/classrooms/antietam-letters-and-diaries-of-soldiers-and-civilians.htm. ↵

- Emma Edwards, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-Fields (Hartford, CT: Williams, 1865), 6. ↵

- C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981), 85. ↵

- Ibid., 158. ↵