What Is the Digestive System?

The digestive system consists of organs that break down food, absorb its nutrients, and expel any remaining waste. Organs of the digestive system are shown in Figure 18.2.218.2.2. Most of these organs make up the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Food actually passes through these organs. The rest of the organs of the digestive system are called accessory organs. These organs secrete enzymes and other substances into the GI tract, but food does not actually pass through them.

Functions of the Digestive System

The digestive system has three main functions relating to food: digestion of food, absorption of nutrients from food, and elimination of solid food waste. Digestion is the process of breaking down food into components the body can absorb. It consists of two types of processes: mechanical digestion and chemical digestion. Mechanical digestion is the physical breakdown of chunks of food into smaller pieces. This type of digestion takes place mainly in the mouth and stomach. Chemical digestion is the chemical breakdown (bonds are broken) of large, complex food molecules into smaller, simpler nutrient molecules that can be absorbed by body fluids (blood or lymph). This type of digestion begins in the mouth and continues in the stomach but occurs mainly in the small intestine.

After food is digested, the resulting nutrients are absorbed. Absorption is the process in which substances pass into the bloodstream or lymph system to circulate throughout the body. The absorption of nutrients occurs mainly in the small intestine. Any remaining matter from food that is not digested and absorbed passes out of the body through the anus in the process of elimination.

Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is basically a long, continuous tube that connects the mouth with the anus. If it were fully extended, it would be about 9 meters (30 feet) long in adults. It includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines. Food enters the mouth and then passes through the other organs of the GI tract where it is digested and/or absorbed. Finally, any remaining food waste leaves the body through the anus at the end of the large intestine. It takes up to 50 hours for food or food waste to make the complete trip through the GI tract.

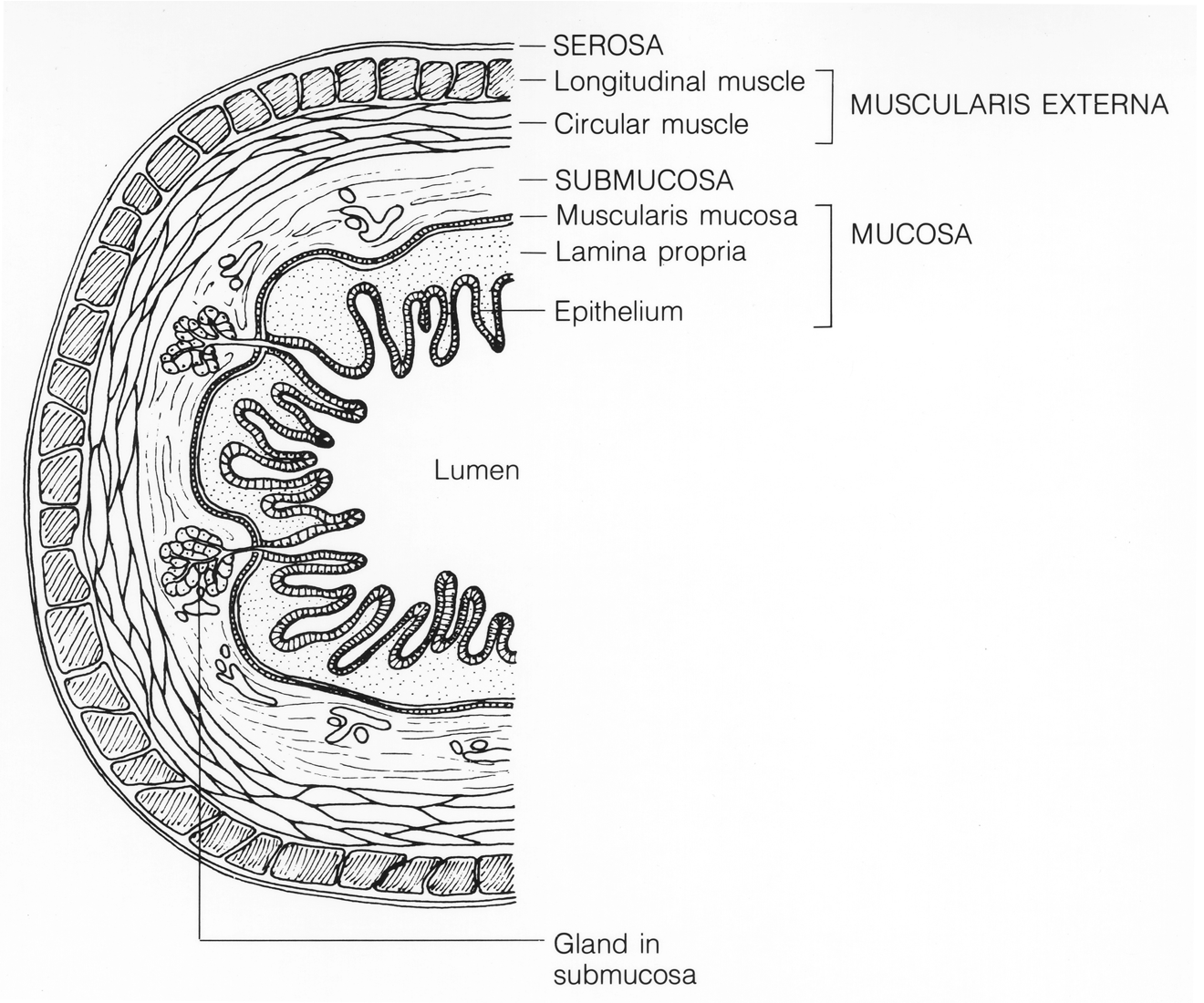

Tissues of the GI Tract

The walls of the organs of the GI tract consist of four different tissue layers, which are illustrated in the figure below: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa.

- The mucosa is the innermost layer surrounding the lumen, or open space within the organs of the GI tract. This layer consists mainly of the epithelium with the capacity to secrete and absorb substances. For example, the epithelium can secrete digestive enzymes and mucus, and it can absorb nutrients and water.

- The submucosa layer consists of connective tissue that contains blood and lymph vessels and also nerves. The vessels are needed to absorb and carry away nutrients after food is digested, and nerves help control the muscles of the GI tract organs.

- The muscularis externa layer contains two types of smooth muscle: longitudinal muscle and circular muscle. The longitudinal muscle runs the length of the GI tract organs and circular muscle encircles the organs. Both types of muscles contract to keep food moving through the track by the process of peristalsis, which is described below.

- The serosa layer is the outermost layer of the walls of GI tract organs. This is a thin layer that consists of connective tissue and separates the organs from surrounding cavities and tissues.

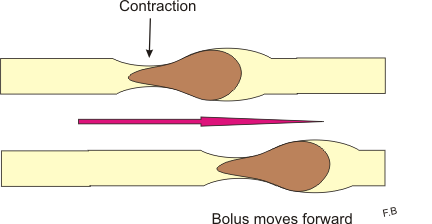

Peristalsis in the GI Tract

The muscles in the walls of GI tract organs enable peristalsis, which is illustrated in the figure below. Peristalsis is a continuous sequence of involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation that moves rapidly along an organ like a wave, similar to the way a wave moves through a spring toy. Peristalsis in organs of the GI tract propels food through the tract.

Immune Function of the GI Tract

The GI tract plays an important role in protecting the body from pathogens. The surface area of the GI tract is estimated to be about 32 square meters or about half the area of a badminton court. This is more than three times the area of the exposed skin of the body, and it provides a lot of surface area for pathogens to invade the tissues of the body. The innermost mucosal layer of the walls of the GI tract provides a barrier to pathogens so they are less likely to be able to enter the blood or lymph circulations. For example, the mucus produced by the mucosal layer contains antibodies that mark many pathogenic microorganisms for destruction. Enzymes in some of the secretions of the GI tract also destroy pathogens. In addition, stomach acids have a very low pH that is fatal for many microorganisms that enter the stomach.

Divisions of the GI Tract

The GI tract is often divided into an upper GI tract and a lower GI tract. For medical purposes, the upper GI tract is typically considered to include all the organs from the mouth through the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. For instructional purposes, it makes more sense to include the mouth through the stomach in the upper GI tract and all of the small intestine as well as the large intestine in the lower GI tract. The latter approach is followed here.

Upper GI Tract

The mouth is the first digestive organ that food enters. The sight, smell, or taste of food stimulates the release of digestive enzymes and other secretions by salivary glands inside the mouth. The major salivary gland enzyme is amylase. It begins the chemical digestion of carbohydrates by breaking down starches into sugar. The mouth also begins the mechanical digestion of food. When you chew, your teeth break, crush, and grind food into increasingly smaller pieces. Your tongue helps to mix the food with saliva and also helps you swallow.

A lump of swallowed food is called a bolus. The bolus passes from the mouth into the pharynx and from the pharynx into the esophagus. The esophagus is a long, narrow tube that carries food from the pharynx to the stomach. It has no other digestive functions. Peristalsis starts at the top of the esophagus when food is swallowed and continues down the esophagus in a single wave, pushing the bolus of food ahead of it.

From the esophagus, food passes into the stomach, where both mechanical and chemical digestion continue. The muscular walls of the stomach churn and mix the food, thus completing mechanical digestion as well as mixing the food with digestive fluids secreted by the stomach. One of these fluids is hydrochloric acid. As well as killing pathogens in food, it gives the stomach the low pH needed by digestive enzymes that work in the stomach. One of these enzymes is pepsin, which chemically digests proteins. The stomach stores the partially digested food until the small intestine is ready to receive it. Food that enters the small intestine from the stomach is in the form of a thick slurry (semi-liquid) called chyme.

Lower GI Tract

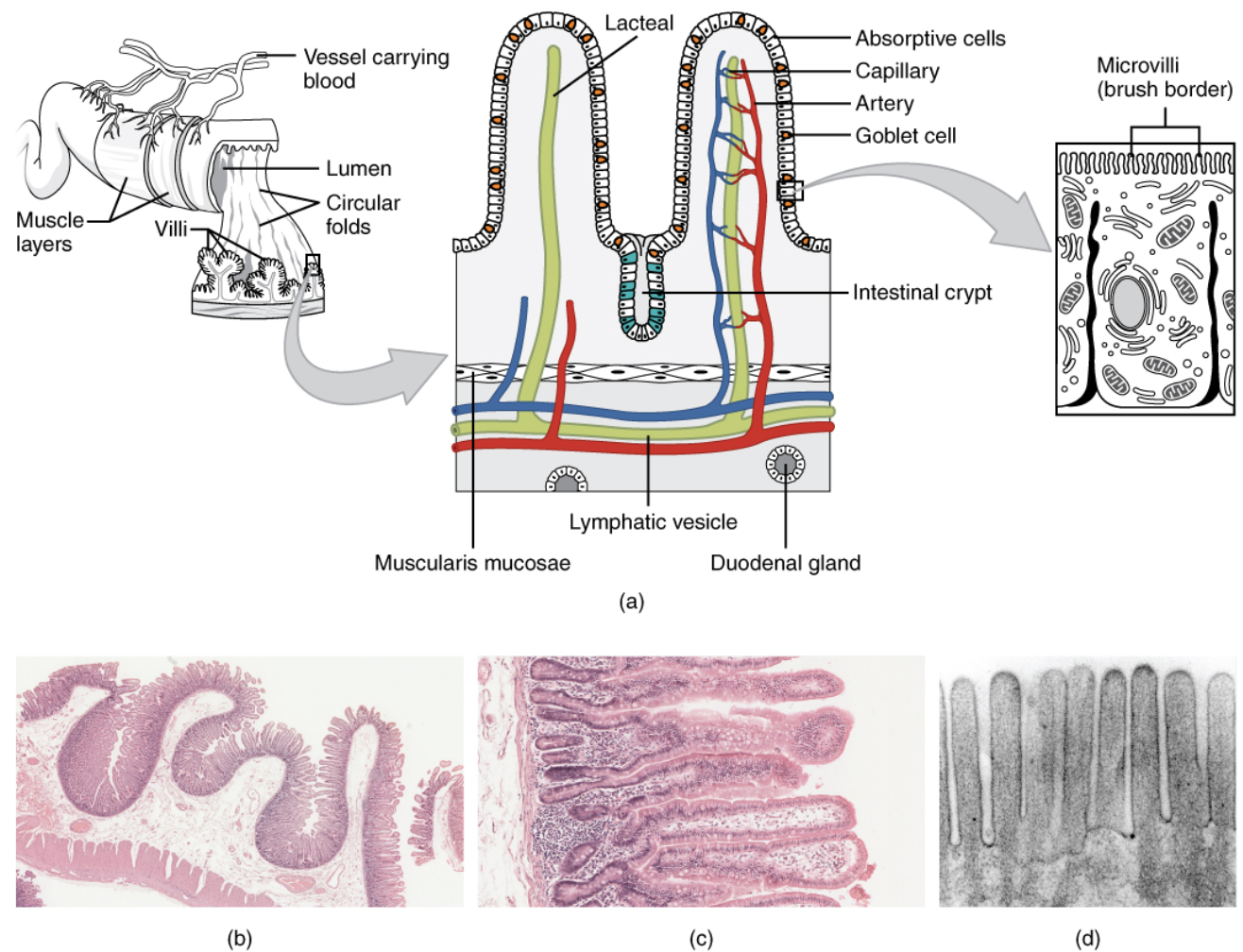

The small intestine is a narrow but very long tubular organ. It may be almost 7 meters (23 feet) long in adults. It is the site of most chemical digestion and virtually all absorption of nutrients. Many digestive enzymes are active in the small intestine, some of which are produced by the small intestine itself, and some of which are produced by the pancreas, an accessory organ of the digestive system. Much of the inner lining of the small intestine is covered by tiny finger-like projections called villi, each of which in turn is covered by even tinier projections called microvilli. These projections, shown in the drawing below, greatly increase the surface area through which nutrients can be absorbed from the small intestine.

The small intestine is made up of three parts:

- The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine. It is also the shortest part. This is where most chemical digestion takes place.

- The jejunum is the second part of the small intestine. This is where most nutrients are absorbed into the blood.

- The ileum is the last part of the small intestine. A few remaining nutrients are absorbed in the ileum. From the ileum, any remaining food waste passes into the large intestine.

From the small intestine, any remaining nutrients and food waste pass into the large intestine. The large intestine is another tubular organ like the small intestine, but it is wider and shorter than the small intestine. It connects the small intestine and the anus. Waste that enters the large intestine is in a liquid state. As it passes through the large intestine, excess water is absorbed from it. The remaining solid waste, called feces, is eventually eliminated from the body through the anus.

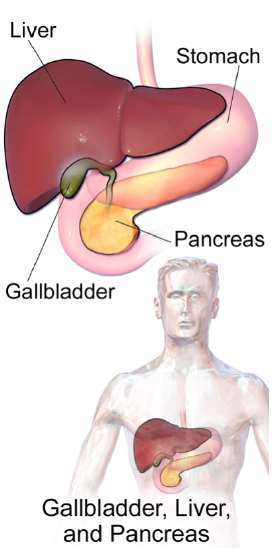

Accessory Organs of the Digestive System

Accessory organs of the digestive system are not part of the GI tract, so they are not sites where digestion or absorption take place. Instead, these organs secrete or store substances that are needed for the chemical digestion of food. The accessory organs include the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. They are shown in Figure 18.2.618.2.6 and described in the text that follows:

- The liver is an organ that has a multitude of functions. Its main digestive function is producing and secreting a fluid called bile, which reaches the small intestine through a duct. Bile breaks down large globules of lipids into smaller ones that are easier for enzymes to chemically digest. Bile is also needed to reduce the acidity of food entering the small intestine from the highly acidic stomach because enzymes in the small intestine require a less acidic environment in order to work.

- The gallbladder is a small sac below the liver that stores some of the bile from the liver. The gallbladder also concentrates the bile by removing some of the water from it. It then secretes the concentrated bile into the small intestine as needed for fat digestion following a meal.

- The pancreas secretes many digestive enzymes and releases them into the small intestine for the chemical digestion of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. The pancreas also helps to lessen the acidity of the small intestine by secreting bicarbonate, a basic substance that neutralizes the acid.

Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract

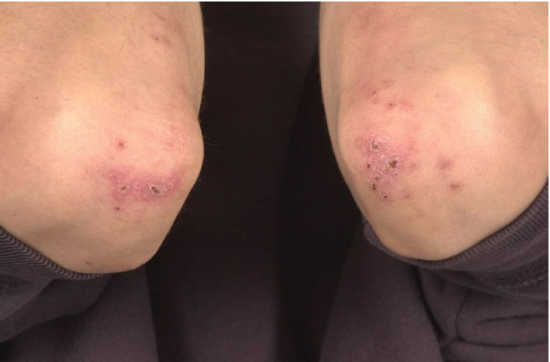

Crohn’s Rash

If you had a skin rash like the one in Figure 18.7.118.7.1, you probably wouldn’t assume that it was caused by a digestive system disease. However, that’s exactly why the individual in the picture has a rash. He has a gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorder called Crohn’s disease. This disease is one of a group of GI tract disorders that are known collectively as inflammatory bowel disease. Unlike other inflammatory bowel diseases, signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease may not be confined to the GI tract.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease is a collection of inflammatory conditions primarily affecting the intestines. The two principal inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Unlike Crohn’s disease, which may affect any part of the GI tract and the joints as well as the skin, ulcerative colitis mainly affects just the colon and rectum. Both diseases occur when the body’s own immune system attacks the digestive system. Both diseases also typically first appear in the late teens or early twenties and occur equally in all sexes and genders.

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that may affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, among other body tissues. The most commonly affected region is the ileum, which is the final part of the small intestine. Signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease typically include abdominal pain, diarrhea (with or without blood), fever, and weight loss. Malnutrition because of faulty absorption of nutrients may also occur. Potential complications of Crohn’s disease include obstructions and abscesses of the bowel. People with Crohn’s disease are also at a slightly greater risk than the general population of developing bowel cancer. Although there is a slight reduction in life expectancy in people with Crohn’s disease, if the disease is well managed, affected people can live full and productive lives.

Crohn’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that lead to impairment of the generalized immune response (called innate immunity). The chronic inflammation of Crohn’s disease is thought to be the result of the immune system “trying” to compensate for the impairment. Dozens of genes are likely to be involved, only a few of which have been identified. Because of the genetic component, close relatives such as siblings of people with Crohn’s disease are many times more likely to develop the disease than people in the general population. Environmental factors that appear to increase the risk of the disease include smoking tobacco and eating a diet high in animal proteins. Crohn’s disease is typically diagnosed on the basis of a colonoscopy, which provides a direct visual examination of the inside of the colon and the ileum of the small intestine.

People with Crohn’s disease typically experience recurring periods of flare-ups followed by remission. There are no medications or surgical procedures that can cure Crohn’s disease, although medications such as anti-inflammatory or immune-suppressing drugs may alleviate symptoms during flare-ups and help maintain remission. Lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and smoking cessation, may also help control symptoms and reduce the likelihood of flare-ups. Surgery may be needed to resolve bowel obstructions, abscesses, or other complications of the disease.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease that causes inflammation and ulcers (sores) in the colon and rectum. Unlike Crohn’s disease, other parts of the GI tract are rarely affected in ulcerative colitis. The primary symptoms of the disease are lower abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Weight loss, fever, and anemia may also be present. Symptoms typically occur intermittently with periods of no symptoms between flare-ups. People with ulcerative colitis have a considerably increased risk of colon cancer and should be screened for colon cancer more frequently than the general population. However, ulcerative colitis seems to reduce primarily the quality of life and not the lifespan.

The exact cause of ulcerative colitis is not known. Theories about its cause involve immune system dysfunction, genetics, changes in normal gut bacteria, and lifestyle factors such as a diet high in animal protein and the consumption of alcoholic beverages. Genetic involvement is suspected in part because ulcerative colitis tends to “run” in families. It is likely that multiple genes are involved. Diagnosis is typically made on the basis of colonoscopy and tissue biopsies.

Lifestyle changes, such as reducing the consumption of animal protein and alcohol, may improve symptoms of ulcerative colitis. A number of medications are also available to treat symptoms and help prolong remission. These include anti-inflammatory drugs and drugs that suppress the immune system. In cases of severe disease, removal of the colon and rectum may be required and can cure the disease.

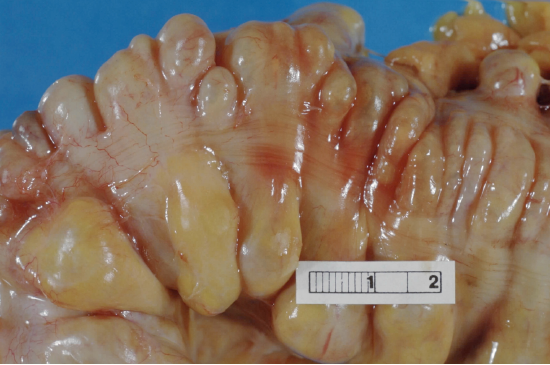

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis is a digestive disease in which tiny pouches in the wall of the large intestine become infected and inflamed. Symptoms typically include lower abdominal pain of sudden onset. There may also be fever, nausea, diarrhea or constipation, and blood in the stool. Having large intestine pouches called diverticula (Figure 18.7.318.7.3) that are not inflamed is called diverticulosis. Diverticulosis is thought to be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors and is more common in people who are obese. Infection and inflammation of the pouches (diverticulitis) occur in about 10 to 25 percent of people with diverticulosis and is more common at older ages. The infection is generally caused by bacteria.

Diverticulitis can usually be diagnosed with a CT scan. Mild diverticulitis may be treated with oral antibiotics and a short-term liquid diet. For severe cases, intravenous antibiotics, hospitalization, and complete bowel rest (no nourishment via the mouth) may be recommended. Complications such as abscess formation or perforation of the colon require surgery.

Peptic Ulcer

A peptic ulcer is a sore in the lining of the stomach or the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). If the ulcer occurs in the stomach, it is called a gastric ulcer; if it occurs in the duodenum, it is called a duodenal ulcer. The most common symptoms of peptic ulcers are upper abdominal pain that often occurs at night and improves with eating. Other symptoms may include belching, vomiting, weight loss, and poor appetite. However, many people with peptic ulcers, particularly older people, have no symptoms. Peptic ulcers are relatively common, with about 10 percent of people developing a peptic ulcer at some point in their life.

The most common cause of peptic ulcers is infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which may be transmitted by food, contaminated water, or human saliva (for example, by kissing or sharing eating utensils). Surprisingly, the bacterial cause of peptic ulcers was not discovered until the 1980s. The scientists who made the discovery are Australians Robin Warren and Barry J. Marshall. Although the two scientists eventually won a Nobel Prize for their discovery, their hypothesis was poorly received at first. To demonstrate the validity of their discovery, Marshall used himself in an experiment. He drank a culture of bacteria from a peptic ulcer patient and developed symptoms of peptic ulcer in a matter of days. His symptoms resolved on their own within a couple of weeks, but he took antibiotics to kill any remaining bacteria at his wife’s urging (apparently because bad breath is also one of the symptoms of H. pylori infection). Marshall’s self-experiment was published in the Australian Medical Journal and is among the most cited articles ever published in the journal.

Another relatively common cause of peptic ulcers is the chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Additional contributing factors may include tobacco smoking and stress, although these factors have not been demonstrated conclusively to cause peptic ulcers independent of H. pylori infection. Contrary to popular belief, diet does not appear to play a role in either causing or preventing peptic ulcers. Eating spicy foods and drinking coffee and alcohol were once thought to cause peptic ulcers. These lifestyle choices are no longer thought to have much if any effect on the development of peptic ulcers.

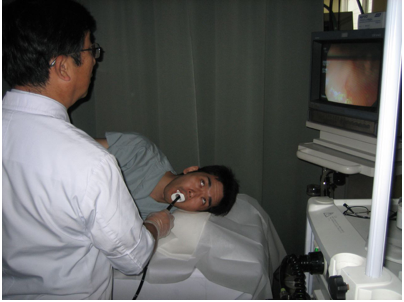

Peptic ulcers are typically diagnosed on the basis of symptoms or the presence of H. pylori in the GI tract. However, endoscopy (Figure 18.7.518.7.5), which allows direct visualization of the stomach and duodenum with a camera, may be required for a definitive diagnosis. Peptic ulcers are usually treated with antibiotics to kill H. pylori, along with medications to temporarily decrease stomach acid and aid in healing. Unfortunately, H. pylori have developed resistance to commonly used antibiotics, so treatment is not always effective. If a peptic ulcer has penetrated so deep into the tissues that it causes perforation of the wall of the stomach or duodenum, then emergency surgery is needed to repair the damage.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is an acute and usually self-limiting infection of the GI tract by pathogens. Symptoms typically include some combination of diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of energy, and dehydration may also occur. The illness generally lasts less than two weeks, even without treatment, but in young children, it is potentially deadly. Gastroenteritis is very common, especially in poorer nations. Worldwide, up to five billion cases occur each year, resulting in about 1.4 million deaths. In the United States, infectious diarrhea is the second most common type of infection after the common cold.

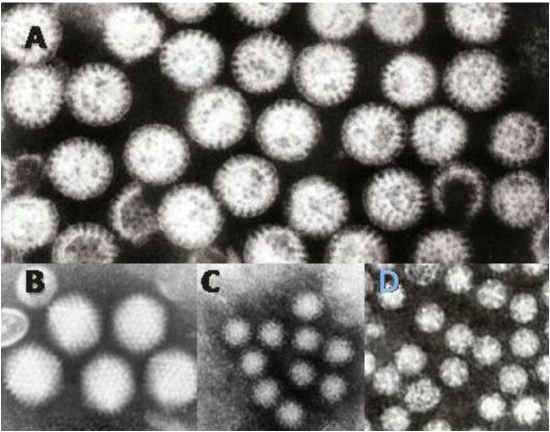

Commonly called “stomach flu,” gastroenteritis is unrelated to the influenza virus, although viruses are the most common cause of the disease (Figure 18.7.618.7.6). In children, rotavirus is most often the cause, whereas norovirus is more likely to be the cause in adults. Besides viruses, other potential causes of gastroenteritis include fungi, protozoa (including Giardia lamblia, described below), and bacteria (most often Escherichia coli or Campylobacter jejuni). Transmission of pathogens may occur due to eating improperly prepared foods or foods left to stand at room temperature, drinking contaminated water, or having close contact with an infected individual.

Gastroenteritis is less common in adults than children, partly because adults have acquired immunity after repeated exposure to the most common infectious agents. Adults also tend to have better hygiene than children. If children have frequently repeated incidents of gastroenteritis, they may suffer from malnutrition, stunted growth, and developmental delays. Many cases of gastroenteritis in children can be avoided by giving them a rotavirus vaccine. Frequent and thorough hand washing can cut down on infections caused by other pathogens.

Treatment of gastroenteritis generally involves increasing fluid intake to replace fluids lost in vomitus or diarrhea. Oral rehydration solution, which is a combination of water, salts, and sugar, is often recommended. In severe cases, intravenous fluids may be needed. Antibiotics are not usually prescribed because they are ineffective against viruses that cause most cases of gastroenteritis.

Giardiasis

Giardiasis, popularly known as beaver fever, is a type of gastroenteritis caused by a GI tract parasite, the single-celled protozoan Giardia lamblia (Figure 18.7.718.7.7). The parasite inhabits the digestive tract of a wide variety of domestic and wild animal species in addition to human beings, including cows, rodents, and sheep as well as beavers (hence its popular name). Giardiasis is one of the most common parasitic infections in people the world over, with hundreds of millions of people infected worldwide each year.

Transmission of G. lamblia is via a fecal-oral route. Those at greatest risk include travelers to countries where giardiasis is common, people who work in child-care settings, backpackers and campers who drink untreated water from lakes or rivers, and people who have close contact with infected people or animals in other settings. In the United States, giardiasis occurs more often during the summer than other seasons, probably because people spend more time outdoors and in wild settings at that time of year.

Symptoms of giardiasis can vary widely. About a third of people with the infection have no symptoms, whereas others have severe diarrhea with poor absorption of nutrients. Problems with absorption occur because the parasites inhibit intestinal digestive enzyme production, cause detrimental changes in microvilli lining the small intestine, and kill off small intestinal epithelial cells. The illness can result in weakness, loss of appetite, stomach cramps, vomiting, and excessive gas. Without treatment, symptoms may continue for several weeks. Treatment with an antibiotic may be needed if symptoms persist longer or are particularly severe.