What Is the Reproductive System?

The reproductive system is the human organ system responsible for the production and fertilization of gametes (sperm or eggs) and carrying of a fetus. Both both sexes gonads produce gametes. A gamete is a haploid cell that combines with another haploid gamete during fertilization, forming a single diploid cell called a zygote. Besides producing gametes, the gonads also produce sex hormones. Sex hormones are endocrine hormones that control the development of sex organs before birth, sexual maturation at puberty, and reproduction once sexual maturation has occurred. Other reproductive system organs have various functions, such as maturing gametes, delivering gametes to the site of fertilization, and providing an environment for the development and growth of an offspring.

Sex Differences in the Reproductive System

The reproductive system is the only human organ system that is significantly different between males and females. Embryonic structures that will develop into the reproductive system start out the same in males and females, but by birth, the reproductive systems have differentiated. How does this happen?

Sex Differentiation

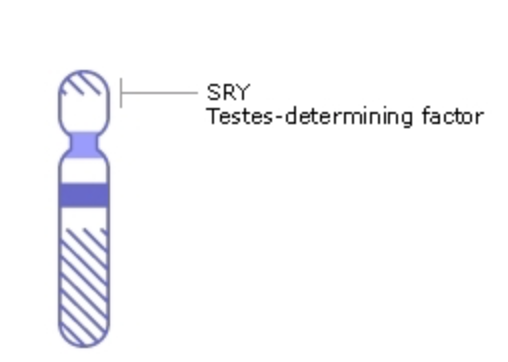

Starting around the seventh week after conception in genetically male (XY) embryos, a gene called SRY on the Y chromosome (Figure 22.2.222.2.2) initiates the production of multiple proteins. These proteins cause undifferentiated gonadal tissue to develop into testes. Testes secrete hormones — including testosterone — that trigger other changes in the developing offspring (now called a fetus), causing it to develop a complete male reproductive system. Without a Y chromosome, an embryo will develop ovaries, that will produce estrogen. Estrogen, in turn, will lead to the formation of the other organs of a female reproductive system.

Homologous Structures

Undifferentiated embryonic tissues develop into different structures in male and female fetuses. Structures that arise from the same tissues in males and females are called homologous structures. The testes and ovaries, for example, are homologous structures that develop from the undifferentiated gonads of the embryo. Likewise, the penis and clitoris are homologous structures that develop from the same embryonic tissues.

Sex Hormones and Maturation

Male and female reproductive systems are different at birth, but they are immature and incapable of producing gametes or sex hormones. Maturation of the reproductive system occurs during puberty when hormones from the hypothalamus and pituitary gland stimulate the testes or ovaries to start producing sex hormones again. The main sex hormones are testosterone and estrogen. Sex hormones, in turn, lead to the growth and maturation of the reproductive organs, rapid body growth, and the development of secondary sex characteristics, such as body and facial hair and breasts.

Role of Sex Hormones in Transgender Treatment

Feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy is the administration of exogenous endocrine agents to induce changes in physical appearance. Since hormone therapy is inexpensive relative to surgery and highly effective in the development of secondary sex characteristics (e.g., facial and body hair in female-to-male [FTM] individuals or breast tissue in male-to-females [MTFs]), hormone therapy is often the first, and sometimes only, medical gender affirmation intervention accessed by transgender individuals looking to develop masculine or feminine characteristics consistent with their gender identity. In some cases, hormone therapy may be required before surgical interventions can be conducted. Trans-females are prescribed estrogen and anti-testosterone medication, such as cyproterone acetate and spironolactone. Trans-men are prescribed testosterone.

Male Reproductive System

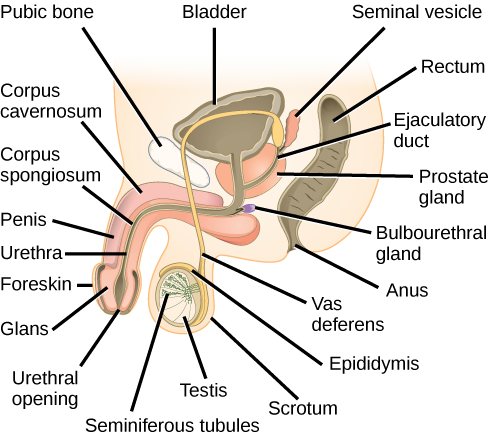

The main structures of the male reproductive system are external to the body and illustrated in Figure 22.2.322.2.3. The two testes (singular, testis) hang between the thighs in a sac of skin called the scrotum. The testes produce both sperm and testosterone. Resting atop each testis is a coiled structure called the epididymis (plural, epididymes). The function of the epididymes is to mature and store sperm. The penis is a tubular organ that contains the urethra and has the ability to stiffen during sexual arousal. Sperm passes out of the body through the urethra during a sexual climax (orgasm). This release of sperm is called ejaculation.

In addition to these organs, there are several ducts and glands that are internal to the body. The ducts, which include the vas deferens (also called the ductus deferens), transport sperm from the epididymis to the urethra. The glands, which include the prostate gland and seminal vesicles, produce fluids that become part of semen. Semen is the fluid that carries sperm through the urethra and out of the body. It contains substances that control pH and provide sperm with nutrients for energy.

Female Reproductive System

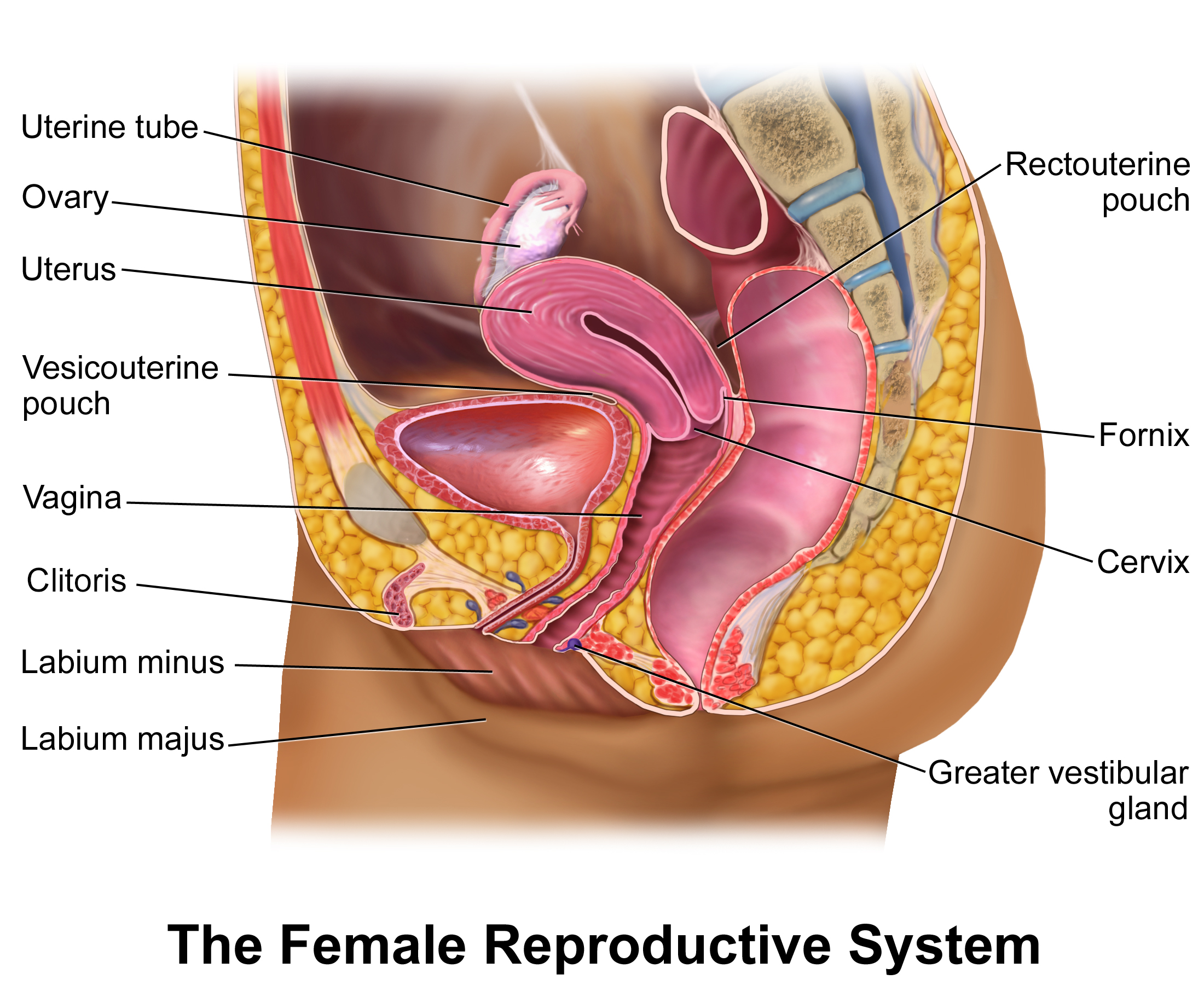

The main structures of the female reproductive system are internal to the body and shown in Figure 22.2.422.2.4. They include the paired ovaries, which are small, ovoid structures that produce eggs and secrete estrogen. The two Fallopian tubes start near the ovaries and end at the uterus. Their function is to transport eggs from the ovaries to the uterus. If an egg is fertilized, it usually occurs while it is traveling through a Fallopian tube. The uterus is a pear-shaped muscular organ that functions to carry a fetus until birth. It can expand greatly to accommodate a growing fetus, and its muscular walls can contract forcefully during labor to push the baby out of the uterus and into the vagina. The vagina is a tubular tract connecting the uterus to the outside of the body. The vagina is where sperm are usually deposited during sexual intercourse and ejaculation. The vagina is also called the birth canal because a baby travels through the vagina to leave the body during birth.

The external structures of the female reproductive system are referred to collectively as the vulva. They include the clitoris, which is homologous to the male penis. They also include two pairs of labia (singular, labium), which surround and protect the openings of the urethra and vagina.

Disorders of the Male Reproductive System

Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is sexual dysfunction characterized by the regular and repeated inability of a sexually mature individual to obtain or maintain an erection. It is a common disorder that affects about 40 percent of people with penises.

Causes of Erectile Dysfunction

The penis normally stiffens and becomes erect when the columns of spongy tissue within the shaft of the penis (the corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum) become engorged with blood. Anything that hampers normal blood flow to the penis may, therefore, interfere with its potential to fill with blood and become erect. The normal nervous control of sexual arousal or penile engorgement may also fail and lead to problems obtaining or maintaining an erection

Specific causes of ED include both physiological and psychological causes. Physiological causes include the use of therapeutic drugs (such as antidepressants), aging, kidney failure, diseases (such as diabetes or multiple sclerosis), tobacco smoking, and treatments for other disorders (such as prostate cancer). Psychological causes are less common but may include stress, performance anxiety, or mental disorders. The risk of ED may also be greater in people with obesity, cardiovascular disease, poor dietary habits, and overall poor physical health. Having an untreated hernia in the groin may also lead to ED.

Treatments for Erectile Dysfunction

Treatment of ED depends on its cause or contributing factors. For example, for tobacco smokers, smoking cessation may bring significant improvement in ED. Improving overall physical health by losing weight and exercising regularly may also be beneficial. The most common first-line treatment for ED, however, is the use of oral prescription drugs, known by brand names such as Viagra® and Cialis®. These drugs help ED by increasing blood flow to the penis. Other potential treatments include topical creams applied to the penis, injection of drugs into the penis, or the use of a vacuum pump that helps draw blood into the penis by applying negative pressure. More invasive approaches may be used as a last resort if other treatments fail. These usually involve surgery to implant inflatable tubes or rigid rods into the penis.

Ironically, the world’s most venomous spider —the Brazilian wandering spider (Figure 22.5.222.5.2) — may offer a new treatment for ED. The venom of this spider is known to cause priapism in humans. Priapism is a prolonged erection that may damage the reproductive organs and lead to infertility if it continues too long. Researchers are investigating one of the components of the spider’s venom as a possible treatment for ED if taken in minute quantities.

Epididymitis

Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis. The epididymis is one of the paired organs within the scrotum where sperms mature and are stored. Discomfort or pain and swelling in the scrotum are typical symptoms of epididymitis, which is a relatively common condition, especially in young individuals. In the U.S. alone, more than half a million cases of epididymitis are diagnosed annually between the ages of 18 to 35.

Acute vs. Chronic Epididymitis

Epididymitis may be acute or chronic. Acute diseases are generally short-term conditions, whereas chronic diseases may last years — or even lifelong.

Acute Epididymitis

Acute epididymitis generally has a fairly rapid onset and is most often caused by a bacterial infection. Bacteria in the urethra can back-flow through the urinary and reproductive structures to the epididymis. In sexually active individuals, many cases of acute epididymitis are caused by sexually transmitted bacteria. Besides pain and swelling, common symptoms of acute epididymitis include redness, warmth in the scrotum, and a fever. There may also be a urethral discharge.

Chronic Epididymitis

Chronic epididymitis is epididymitis that lasts for more than three months. In some, the condition may last for years. It may occur with or without a bacterial infection being diagnosed. Sometimes, it is associated with lower back pain that occurs after an activity that stresses the lower back, such as heavy lifting or a long period spent driving a vehicle.

Treatment of Epididymitis

If a bacterial infection is suspected, both acute and chronic epididymitis are generally treated with antibiotics. For chronic epididymitis, antibiotic treatment may be prescribed for as long as four to six weeks to ensure the complete eradication of any possible bacteria. Additional treatments often include anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce inflammation of the tissues and painkillers to control the pain, which may be severe. Physically supporting the scrotum and applying cold compresses may also be recommended to help relieve swelling and pain.

Regardless of symptoms, treatment is important for both acute and chronic epididymitis, because major complications may occur otherwise. Untreated acute epididymitis may lead to an abscess — which is a buildup of pus — or to the infection spreading to other organs. Untreated chronic epididymitis may lead to permanent damage to the epididymis and testis, and it may even cause infertility.

Male Reproductive Cancers

Why does the Brazilian hospital pictured below have a huge blue mustache on its “face”? The mustache is a symbol of “Movember.” This is an international campaign to raise awareness of prostate cancer, as well as money to fund prostate cancer research.

Prostate Cancer

The prostate gland is an organ located in the male pelvis. The urethra passes through the prostate gland after it leaves the bladder and before it reaches the penis. The function of the prostate is to secrete zinc and other substances into semen during ejaculation. In the United States, prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in people carrying prostate gland. About 80 percent of Americans individuals with the prostate will have cancerous cells in their prostate gland by the age of 80.

How Prostate Cancer Occurs

Prostate cancer occurs when glandular cells of the prostate mutate into tumor cells. Eventually, the tumor, if undetected, may invade nearby structures, such as the seminal vesicles. Tumor cells may also metastasize and travel in the bloodstream or lymphatic system to organs elsewhere in the body. Prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to the bones, lymph nodes, rectum, or lower urinary tract organs.

Symptoms of Prostate Cancer

Early in the course of prostate cancer, there may be no symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they mainly involve urination, because the urethra passes through the prostate gland. The symptoms typically include frequent urination, difficulty starting and maintaining a steady stream of urine, blood in the urine, and painful urination. Prostate cancer may also cause problems with sexual function, such as difficulty achieving an erection or painful ejaculation.

Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer

Some factors that increase the risk of prostate cancer can be changed, and others cannot.

- Risk factors that can be changed include a diet high in meat, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and high blood pressure.

- Risk factors that cannot be changed include older age, a family history of prostate cancer, and African ancestry. Family history is an important risk factor, so genes are clearly involved. Many different genes have been implicated.

Diagnosing Prostate Cancer

The only definitive test to confirm a diagnosis of prostate cancer is a biopsy. In this procedure, a small piece of the prostate gland is surgically removed and then examined microscopically. A biopsy is done only after less invasive tests have found evidence that a patient may have prostate cancer.

A routine exam by a doctor may find a lump on the prostate, which might be followed by a blood test that detects an elevated level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA). PSA is a protein secreted by the prostate that normally circulates in the blood. Higher-than-normal levels of PSA can be caused by prostate cancer, but they may also have other causes. Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might also be undertaken to provide images of the prostate gland and additional information about cancer.

Treatment of Prostate Cancer

The average age at which men are diagnosed with prostate cancer is 70. Prostate cancer typically is such a slow-growing cancer that elderly patients may not require treatment. Instead, the patients are watched carefully over the subsequent years to make sure the cancer isn’t growing and posing an immediate threat — an approach that is called active surveillance. It is used for at least 50 percent of patients who are expected to die from other causes before their prostate cancer causes symptoms.

Treatment of younger patients — or those with more aggressively growing tumors — may include surgery to remove the prostate, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy (such as brachytherapy, see photo below). All of these treatment options can have significant side effects, such as erectile dysfunction or urinary incontinence. Patients should learn the risks and benefits of the different treatments, and discuss them with their healthcare provider to decide on the best treatment options for their particular case.

Testicular Cancer

Reproductive cancer that is rare and most commonly affects young individuals is testicular cancer. The testes are the paired reproductive organs in the scrotum that produce sperm and secrete testosterone. The risk of testicular cancer is about four to five times greater in individuals of European than African ancestry. The cause of this difference is unknown.

Signs and Symptoms of Testicular Cancer

One of the first signs of testicular cancer is often a lump or swelling in one of the two testes. The lump may or may not be painful. If pain is present, it may occur as a sharp pain or a dull ache in the lower abdomen or scrotum. Some people with testicular cancer report a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum. Testicular cancer does not commonly spread beyond the testis, but if it does, it most often spreads to the lungs, where it may cause shortness of breath or a cough.

Diagnosis of Testicular Cancer

The main way that testicular cancer is diagnosed is by detection of a lump in the testis. This is likely followed by further diagnostic tests. An ultrasound may be done to determine the exact location, size, and characteristics of the lump. Blood tests may be done to identify and measure tumor-marker proteins in the blood that are specific to testicular cancer. CT scans may also be done to determine whether the disease has spread beyond the testis. However, unlike the case with prostate cancer, a biopsy is not recommended, because it increases the risk of cancer cells spreading into the scrotum.

Treatment of Testicular Cancer

Testicular cancer has one of the highest cure rates of all cancers. Three basic types of treatment for testicular cancer are surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy. Generally, the initial treatment is surgery to remove the affected testis. If the cancer is caught at an early stage, the surgery is likely to cure the cancer, and has nearly a 100 percent five-year survival rate. When just one testis is removed, the remaining testis (if healthy) is adequate to maintain fertility, hormone production, and other normal functions. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may follow surgery to kill any tumor cells that might exist outside the affected testis, even when there is no indication that the cancer has spread. In many cases, however, surgery is followed by surveillance instead of additional treatments.

Disorders of the Female Reproductive System

Vaccinating Against Cancer

Can a vaccine prevent cancer? In the case of cervical cancer, it can. Cervical cancer is one of three disorders of the female reproductive system described in detail in this concept. Of the three, only cervical cancer can be prevented with a vaccine.

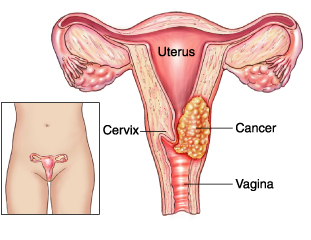

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer occurs when cells of the cervix (neck of the uterus) grow abnormally and develop the ability to invade nearby tissues or spread to other parts of the body, such as the abdomen or lungs. Figure 22.9.222.9.2 shows the location of the cervix and the appearance of normal and abnormal cervical cells when examined with a microscope.

Cervical Cancer Prevalence and Death Rates

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the second most common type of cancer (after breast cancer) and the fourth most common cause of cancer death. In the United States and other high-income nations, the widespread use of cervical cancer screening has detected many cases of precancerous cervical changes and has dramatically reduced rates of cervical cancer deaths. About three-quarters of cervical cancer cases occur in developing countries, where routine screening is less likely because of cost and other factors. Cervical cancer is also the most common cause of cancer death in low-income countries.

Symptoms of Cervical Cancer

Early in the development of cervical cancer, there are typically no symptoms. As the disease progresses, however, symptoms are likely to occur. The symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, or pain during sexual intercourse. Unfortunately, by the time symptoms start to occur, cervical cancer has typically progressed to a stage at which treatment is less likely to be successful.

Cervical Cancer Causes and Risk Factors

More than 90 percent of cases of cervical cancer are caused at least in part by human papillomavirus (HPV), which is a sexually transmitted virus that also causes genital warts. Figure 22.9.322.9.3 shows how HPV infection can cause cervical cancer by interfering with a normal cell division checkpoint. When HPV is not present, cervical cells containing mutations are not allowed to divide, so the cervix remains healthy. When HPV is present, however, cervical cells with mutations may be allowed to divide, leading to uncontrolled growth of mutated cells and the formation of a tumor.

Other risk factors for cervical cancer include smoking, a weakened immune system (for example, due to HIV infection), use of birth control pills, becoming sexually active at a young age, and having many sexual partners. However, these risk factors are less important than HPV infection. Instead, the risk factors are more likely to increase the risk of cervical cancer in individuals who are already infected with HPV. For example, among HPV-infected, current and former smokers have roughly two to three times the incidence of cervical cancer as non-smokers. Passive smoking is also associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer but to a lesser extent.

Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer

Diagnosis of cervical cancer is typically made by looking for microscopic abnormal cervical cells in a smear of cells scraped off the cervix. This is called a Pap smear. If cancerous cells are detected or suspected in the smear, this test is usually followed up with a biopsy to confirm the Pap smear results. Medical imaging (by CT scan or MRI, for example) is also likely to be done to provide more information, such as whether the cancer has spread.

Prevention of Cervical Cancer

It is now possible to prevent HPV infection with a vaccine. The first HPV vaccine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2006. The vaccine protects against the strains of HPV that have the greatest risk of causing cervical cancer. It is thought that widespread use of the vaccine will prevent up to 90 percent of cervical cancer cases. Current recommendations are to be given the vaccine between the ages of nine and 26. (All sexes should be vaccinated against HPV, because the virus may also cause cancer of the penis and certain other cancers.) The vaccine is effective only if it is given before HPV infection has occurred. Using condoms during sexual intercourse can also help prevent HPV infection and cervical cancer, in addition to preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (such as HIV).

Even for those who have received the HPV vaccine, there is still a small risk of developing cervical cancer. Therefore, it is recommended that individuals with cervix continue to be examined with regular Pap smears.

Treatment of Cervical Cancer

Treatment of cervical cancer generally depends on the stage at which the cancer is diagnosed, but it is likely to include some combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy. Outcomes of treatment depend largely on how early the cancer is diagnosed and treated. For surgery to cure cervical cancer, the entire tumor must be removed with no cancerous cells found at the margins of the removed tissue on microscopic examination. If cancer is found and treated very early when it is still in the microscopic stage, the five-year survival rate is virtually 100 percent.

Vaginitis

Vaginitis is inflammation of the vagina — and sometimes the vulva, as well. Symptoms may include a discharge that is yellow, gray, or green; itching; pain; and a burning sensation. There may also be a foul vaginal odor and pain or irritation with sexual intercourse.

Causes of Vaginitis

About 90 percent of cases of vaginitis are caused by infection with microorganisms. Most commonly, vaginal infections are caused by the yeast Candida albicans (Figure 22.9.422.9.4). Such infections are referred to as vaginal candidiasis. Other possible causes of vaginal infections include bacteria, especially Gardnerella vaginalis, and some single-celled parasites, notably the protist parasite Trichomonas vaginalis, which is usually transmitted through vaginal intercourse. The risk of vaginal infections may be greater in those who wear tight clothing, are taking antibiotics for another condition, use birth control pills, or have improper hygiene. Poor hygiene allows organisms that are normally present in the stool (such as yeast) to contaminate the vagina. Most of the remaining cases of vaginitis are due to irritation by — or allergic reactions to — various products. These irritants may include condoms, spermicides, soaps, douches, lubricants, and even semen. Using tampons or soaking in hot tubs may be additional causes of this type of vaginitis.

Diagnosis of Vaginitis

Diagnosis of vaginitis typically begins with symptoms reported by the patient. This may be followed by a microscopic examination or culture of the vaginal discharge in order to identify the specific cause. The color, consistency, acidity, and other characteristics of the discharge may be predictive of the causative agent. For example, infection with Candida albicans may cause a cottage cheese-like discharge with a low pH, whereas infection with Gardnerella vaginalis may cause a discharge with a fish-like odor and a high pH.

Prevention of Vaginitis

Prevention of vaginitis includes wearing loose cotton underwear that helps keep the vulva dry. Yeasts and bacteria that may cause vaginitis tend to grow best in a moist environment. It is also important to avoid the use of perfumed soaps, personal hygiene sprays, and douches, all of which may upset the normal pH and bacterial balance in the vagina. To help avoid vaginitis caused by infection with Trichomonas vaginalis, the use of condoms during sexual intercourse is advised.

Treatment of Vaginitis

The appropriate treatment of vaginitis depends on the cause. In many cases of vaginitis, there is more than one cause, and all of the causes must be treated to ensure a cure.

- Yeast infections of the vagina are typically treated with topical anti-fungal medications, which are available over the counter. The medications may be in the form of tablets or creams that are inserted into the vagina. Depending on the particular medication used, treatment may involve one, three, or seven days of application.

- Bacterial infections of the vagina are usually treated with antibiotics. These may be taken orally as pills or applied topically to the vagina in creams.

- Trichomonas vaginalis infections of the vagina are generally treated with a single dose of an oral antibiotic. Sexual partners should be treated at the same time, and intercourse should be avoided for at least a week until both partners have completed treatment and been followed-up by a physician.

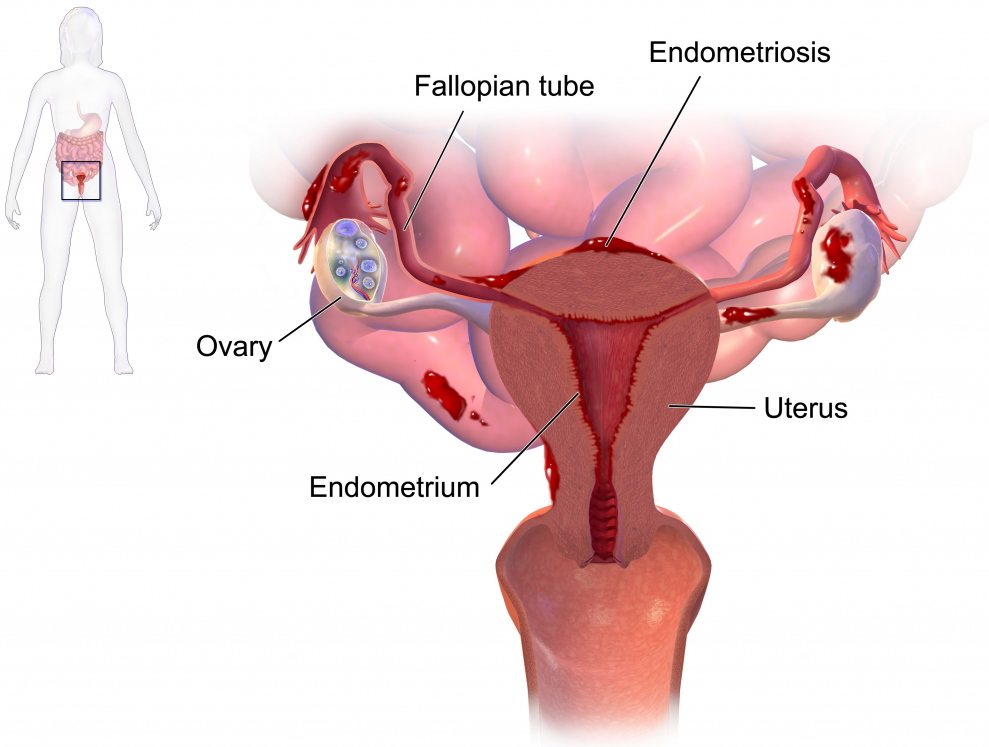

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a disease in which endometrial tissue, which normally grows inside the uterus, grows outside of the uterus (Figure 22.9.522.9.5). Most often, the endometrial tissue grows around the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, and uterus. In rare instances, the tissue may grow elsewhere in the body. The areas of endometriosis typically bleed each month during the menstrual period, and this often results in inflammation, pain, and scarring. An estimated six to ten percent of individuals with the uterus are believed to have endometriosis. It is most common in their thirties and forties, and only rarely occurs before menarche or after menopause.

Signs and Symptoms of Endometriosis

The main symptom of endometriosis is pelvic pain, which may range from mild to severe. There appears to be little or no relationship between the amount of endometrial tissue growing outside the uterus and the severity of the pain. For many with the disease, the pain occurs mainly during menstruation. However, nearly half of those affected have chronic pelvic pain. The pain of endometriosis may be caused by bleeding in the pelvis, which triggers inflammation. Pain can also occur from internal scar tissue that binds internal organs to each other.

Another problem often associated with endometriosis is infertility, or the inability to conceive or bear children. Among patients with endometriosis, up to half may experience infertility. Infertility can be related to scar formation or to anatomical distortions due to the abnormal endometrial tissue. Other possible symptoms of endometriosis may include diarrhea or constipation, chronic fatigue, nausea and vomiting, headaches, and heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding.

Causes of Endometriosis

The causes of endometriosis are not known for certain, but several risk factors have been identified, including a family history of endometriosis. People who have a genetic relationship with a person with endometriosis have about six times the normal risk of developing the disease themselves. It has been suggested that endometriosis results from mutations in several genes. It is likely that endometriosis is multifactorial, involving the interplay of several factors.

At the physiological level, the predominant idea for how endometriosis comes about is retrograde menstruation. This happens when some of the endometrial debris from a menstrual flow exits the uterus through the Fallopian tubes, rather than through the vagina. The debris then attaches itself to the outside of organs in the abdominal cavity, or to the lining of the abdominal cavity itself. Retrograde menstruation, however, does not explain all cases of endometriosis, so other factors are apparently involved. Suggestions include environmental toxins and autoimmune responses.

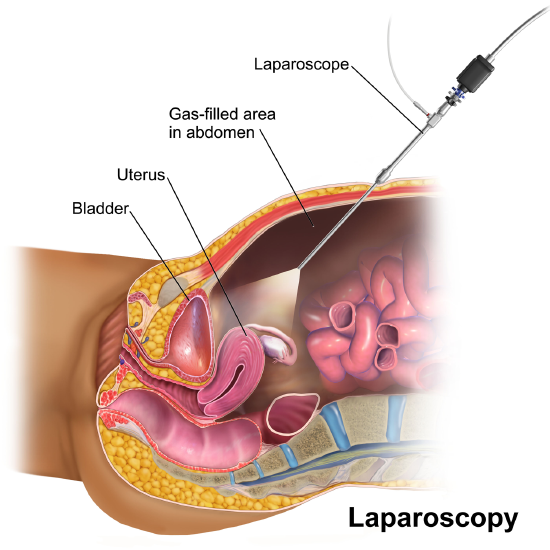

Diagnosis of Endometriosis

Diagnosis of endometriosis is usually based on self-reported symptoms and a physical examination by a doctor, often combined with medical imaging, such as ultrasonography. The only way to definitively diagnose endometriosis, however, is through visual inspection of the endometrial tissue. This can be done with a surgical procedure called laparoscopy, in which a tiny camera is inserted into the abdomen through a small incision (Figure 22.9.622.9.6). The camera allows the physician to visually inspect the area where endometrial tissue is suspected.

Treatment of Endometriosis

The most common treatments for endometriosis are medications to control the pain, and surgery to remove the abnormal tissue. Frequently used pain medications are non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), such as naproxen. Opiates may be used in cases of severe pain. Laparoscopy can be used to surgically treat endometriosis, as well as to diagnose the condition. In this type of surgery, an additional small incision is made to insert instruments that the surgeon can manipulate externally in order to burn (cauterize) or cut away the endometrial growths. In younger patients who want to have children, surgery is conservative to keep the reproductive organs intact and functional. However, with conservative surgery, endometriosis recurs in 20 to 40 percent of cases within five years of the surgery. In older patients who have completed childbearing, hysterectomy may be undertaken to remove all or part of the internal reproductive organs. This is the only procedure that is likely to cure endometriosis and prevent relapses.

Candela Citations

- Reproductive System. Authored by: Contributed by Suzanne Wakim & Mandeep Grewal Professors (Cell Molecular Biology & Plant Science) at Butte College. Located at: https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Human_Biology/Book%3A_Human_Biology_(Wakim_and_Grewal)/22%3A_Reproductive_System/22.02%3A_Introduction_to_the_Reproductive_System. Project: Book: Human Biology (Wakim & Grewal). License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial