Jennifer Miller

It is a challenge to create an origin story about a field of study, in this instance: queer theory, because ideas are not birthed in a moment, a day, or even a year. They build on what has come before, reflect on it, challenge it, seek to bend or break it, and only eventually, and only sometimes, become an identifiable entity with a name given to them. The story of queer theory’s emergence is entwined with queer activism and as much a product of a historical moment as it is a transformative force changing how gender and sexuality are understood in disciplines throughout the university and, increasingly, outside of academia.

In the late 1980s, direct action groups like AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) formed. Larry Kramer created ACT UP in 1987 to demand politicians, the medical community, drug manufacturers, and the public, acknowledge the AIDS epidemic. The group’s motto was, and remains, “Silence=Death” (“ACT UP New York,” n.d.).

RESOURCES

Visit ACT UP’s official website

ACT UP’s official logo

Listen to Making Gay History: The Podcast’s interview with ACT UP founder Larry Kramer

A few years later, the term queer theory began to circulate and quickly gained momentum within academic circles. Film theorist Teresa de Lauretis coined the term queer theory at a University of California – Santa Cruz conference about lesbian and gay sexualities in February 1990 (1991, iii). The conference proceedings were later collected in a 1991 special issue of differences: a feminist cultural studies journal. In her introduction to the special issue, de Lauretis outlines the central features of queer theory, sketching the field in broad strokes that have held up remarkably well (1991).

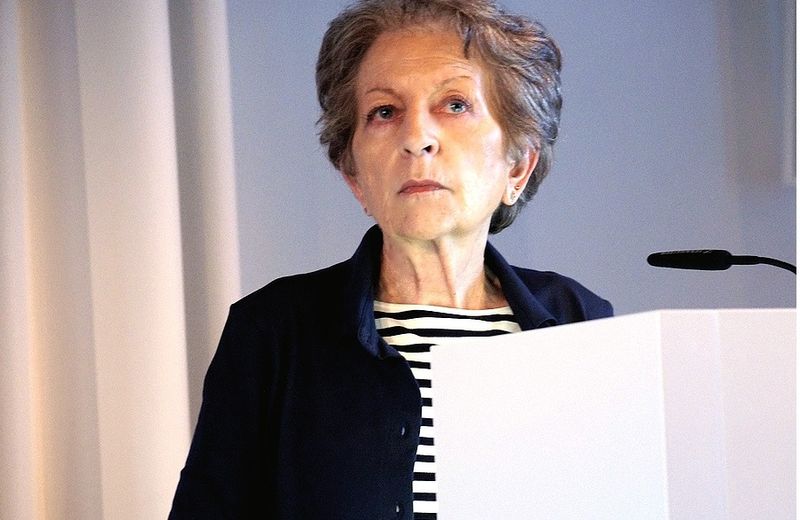

Taresa De Lauretis

In her introduction, de Lauretis suggested gay and lesbian sexualities should be studied, not as deviations of heterosexuality, but on their own terms. She went on to claim gay and lesbian sexualities should be “understood and imagined as forms of resistance to cultural homogenization, counteracting dominant discourses” (1991, iii). According to de Lauretis, and queer theorists more generally, lesbian and gay sexualities enact non-normative intimate and social modes of relating; they put new things in the world and those new things have transformative potential.

De Lauretis used the term queer to create critical distance from Lesbian and Gay Studies. Lesbian and Gay Studies courses began to appear in the 1970s with programs slowly emerging in the 1980s. de Lauretis claimed that within Lesbian and Gay Studies differences were collapsed and the experience of white middle-class gay men was privileged. She notes that although it became standard to refer to lesbians and gays in the 1980s the “and” obscured differences instead of revealing them (1991, vi). In addition to sexuality, de Lauretis hoped queer theory would identify and trouble other “constructed silences,” for instance those of race, ethnicity, class, and gender.

Her introduction to differences illustrates a desire to break with the past and transform the future by developing new ways of conceptualizing sexual identities in the present of the 1990s.

Both sites of critical queerness, activism and scholarship, reject liberal ideals of privacy, the goal of formal equality under the law, and the desirability of assimilation into existing social institutions. Instead, queer theory and activism demand publicness, reject civility, and challenge the legitimacy, naturalness, and intrinsic value of institutions from marriage to the military, which regulate gender and sexuality (Duggan 2001, 219). Of course, this very critical, very radical relationship to the normative appears in times prior to the late-1980s and places other than the United States, but it is then and there that queer activism and queer theory are named and begin to be, however hesitantly, defined.

This chapter explores the development of queer theory from the 1990s to the present. Notably, the idea that queer sexualities and genders resist institutional and discursive regimes of normativity creating new ways of understanding self, as well as intimacy and sociality, has remained central to queer theory.

Chapter Overview

Section One, “The Constructionist Turn,” explores the difference between essentialist and constructionist theories of identity and discusses the implications of the constructionist turn for theorizations of gender and sexuality.

Section Two, “Gender Performativity,” introduces the idea of performativity and further explores implications of the constructionist turn, this time through a discussion of gender.

Section Three, “Transgender Studies,” explores the emergence of transgender activism and studies alongside Queer Studies in the 1990s.

Section Four, “Against Normativity,” maps out queer theoretical investments in resistance to regimes of normativity, both discursive and institutional.

Section Five, “Queer Politics, Transformative Politics,” explores the queer potential of intersectional community building. A brief conclusion identifies queer theory’s commitments to the basic ideas laid out by de Lauretis nearly thirty years ago.

Candela Citations

- Thirty Years of Queer Theory. Authored by: Jennifer Miller. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Taresa de Lauretis. Authored by: Nikisul. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Teresa_de_Lauretis.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike