A detailed look at electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions (EAS)

As outlined in the previous section, the basic mechanism for EAS involves electrophilic addition to form a non-aromatic Wheland intermediate, which then loses H+ through electrophile elimination. The Wheland intermediate is stabilized by resonance, but it is still much less stable than the starting material; this loss of aromaticity means that the first step (electrophilic addition) is always the rate determining step in EAS. The second step (electrophile addition) regenerates the aromatic system and it is a faster step.

Many electrophiles (such as Br2) are not sufficiently electrophilic to react on their own, so many EAS reactions rely on a catalyst in order to activate the electrophile. These catalysts are always either Bronsted-Lowry acids or Lewis acids.

The following examples of EAS, beginning with bromination, serve to illustrate how the reaction works in practice.

Bromination and chlorination

A chlorine or bromine may be introduced using the element (Cl2, Br2) in the presence of the related iron(III) halide (FeCl3 or FeBr3) as the Lewis acid catalyst. However, since iron(III) halides are easily deactivated by water from the air, it is common to use iron metal powder, since this reacts easily with Cl2 or Br2 to form FeCl3 or FeBr3 respectively. The mechanism (shown for bromination) is a typical EAS, comprising (1) electrophile activation (by coordination), then (2) electrophilic addition to form the Wheland intermediate, and finally (3) electrophile elimination to lose H+.

Step 1: Formation of the electrophile by reaction of Br2 with FeBr3.

Step 2: Electrophilic addition of activated bromine

Step 3: Electrophile elimination from the Wheland Intermediate to form the aryl bromide product

The free energy reaction coordinate diagram for this reaction is shown below. It has been simplified to use pre-formed Br+, so in effect it starts at step 2 in the above mechanism. Note that the rate determining step is where the high-energy Wheland Intermediate is formed by electrophilic attack of the Br+ on the aromatic ring. This intermediate is much less stable than the aromatic reactant and aromatic product, because it is not aromatic and it is charged – though it is somewhat stabilized by delocalization of the + charge through resonance.

Free energy reaction coordinate diagram for bromination of benzene to produce bromobenzene

Also, an animated diagram of this mechanism may be viewed.

This mechanism for electrophilic aromatic substitution should be considered in context with other mechanisms involving carbocation intermediates. These include SN1 and E1 reactions of alkyl halides, and Brønsted acid addition reactions of alkenes.

To summarize, when carbocation intermediates are formed one can expect them to react further by one or more of the following modes:

1. The cation may bond to a nucleophile to give a substitution or addition product (coordination).

2. The cation may transfer a proton to a base, giving a double bond product (electrophile elimination).

3. The cation may rearrange to a more stable carbocation, and then react by mode #1 or #2.

SN1 and E1 reactions are respective examples of the first two modes of reaction. The second step of alkene addition reactions proceeds by the first mode, and any of these three reactions may exhibit molecular rearrangement if an initial unstable carbocation is formed. The carbocation intermediate in electrophilic aromatic substitution (the Wheland intermediate) is stabilized by charge delocalization (resonance) so it is not subject to rearrangement. In principle it could react by either mode 1 or 2, but the energetic advantage of reforming an aromatic ring leads to exclusive reaction by mode 2 (i.e., proton loss).

Synthesis of benzene derivatives via electrophilic aromatic substitution

| Reaction | Reagent | Catalyst | Product | E+ or E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halogenation | X2 (X=Cl, Br)

X2 (X = I) |

FeX3

HNO3 |

ArCl, ArBr

ArI |

X+

H2O−I+ |

| Nitration | HNO3 | H2SO4 | ArNO2 | +NO2 |

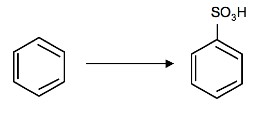

| Sulfonation | H2SO4 or H2S2O7 | None | ArSO3H | SO3 |

| Friedel-Crafts alkylation | RX, ArCH2X | AlCl3 | Ar-R, Ar-CH2Ar | R+ |

| ROH | HF, H2SO4, or BF3 | Ar-R | R+ | |

| RCH=CH2 | H3PO4 or HF | Ar-CHRCH3 | R+ | |

| Friedel-Crafts acylation | RCOCl | AlCl3 | Ar-COR | RC+=O |

Electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions – Halogenation

Study Note

The general mechanism is the key to understanding electrophilic aromatic substitution. You will see similar equations written for nitration, sulfonation, acylation, etc., but the general mechanism is always the same – the major difference being the identity of the electrophile in each case. All involve an electrophilic addition step which is quickly followed by an electrophile elimination step.

Halogenation is an example of electrophillic aromatic substitution. In electrophilic aromatic substitutions, a benzene is attacked by an electrophile which results in substition of hydrogens. However, halogens are not electrophillic enough to break the aromaticity of benzenes, which require a catalyst (such as FeCl3) to activate. See above for a detailed examination of the mechanism for bromination of benzene.

Exercises

1. What reagents would you need to get the given product?

2. What is the major product given the reagents below?

3. Draw the formation of Cl+ from AlCl3 and Cl2. (AlCl3 acts like FeCl3)

4. Draw the mechanism of the reaction between Cl+ and benzene.

Solutions

Nitration and Sulfonation

Nitration of Benzene

The source of the nitronium ion is through the protonation of nitric acid by sulfuric acid, which causes the loss of a water molecule and formation of a nitronium ion.

Sulfuric acid activation of nitric acid

The first step in the nitration of benzene is to activate HNO3 with sulfuric acid to produce a stronger electrophile, the nitronium ion.

Because the nitronium ion is a good electrophile, it is attacked by benzene to produce nitrobenzene.

Mechanism

(Resonance forms of the intermediate can be seen in the generalized electrophilic aromatic substitution)

Sulfonation of benzene

Sulfonation is a reversible reaction that produces benzenesulfonic acid by adding sulfur trioxide and fuming sulfuric acid. The reaction is reversed by adding hot aqueous acid to benzenesulfonic acid to produce benzene.

Mechanism

To produce benzenesulfonic acid from benzene, fuming sulfuric acid and sulfur trioxide are added. Fuming sulfuric acid, also refered to as oleum, is a concentrated solution of dissolved sulfur trioxide in sulfuric acid. The sulfur in sulfur trioxide is electrophilic because the oxygens pull electrons away from it because oxygen is very electronegative. The benzene attacks the sulfur (and subsequent proton transfers occur) to produce benzenesulfonic acid.

Reverse sulfonation

Sulfonation of benzene is a reversible reaction. Sulfur trioxide readily reacts with water to produce sulfuric acid and heat. Therefore, by adding heat to benzenesulfonic acid in diluted aqueous sulfuric acid the reaction is reversed.

Further applications of sulfonation

Because sulfonation is a reversible reaction, it can also be used in further substitution reactions in the form of a directing blocking group because it can be easily removed. The sulfonic group blocks the carbon from being attacked by other substituents and after the reaction is completed it can be removed by reverse sulfonation. Benzenesulfonic acids are also used in the synthesis of detergents, dyes, and sulfa drugs. Benzenesulfonyl chloride is a precursor to sulfonamides, which are used in chemotherapy.

Outside Links

Aromatic Sulfonation

- Interactive 3D Reaction: http://www.chemtube3d.com/Electrophi…20benzene.html

Aromatic Nitration

- Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitration

- Interactive 3D Reaction: http://www.chemtube3d.com/Electrophi…20benzene.html

Exercises

1. What is/are the required reagent(s)for the following reaction:

2. What is the product of the following reaction:

3. Why is it important that the nitration of benzene by nitric acid occurs in sulfuric acid?

4. Write a detailed mechanism for the sulfonation of benzene, including all resonance forms.

5. Draw an energy diagram for the nitration of benzene. Draw the intermediates, starting materials, and products. Label the transition states.

Solutions

Reduction of nitro compounds

Aromatic nitro compounds have many uses, for example in explosives such as TNT. However, the nitro group is often reduced to produce an aromatic amine (called an “aniline”). There are no good, general ways to prepare an aniline (ArNH2) directly from the parent aromatic (Ar-H) by EAS or related methods, so usually aromatic amines are made by nitration followed by reduction. The two main ways to perform the reduction are:

- Hydrogenation using hydrogen gas in the presence of palladium on activated charcoal (Pd on C), or

- Reduction with a metal such as iron or tin in hydrochloric acid, followed by neutralization with a NaOH to release the aniline base.

Historically, this chemistry was very important in the production of synthetic dyes, beginning in the 19th century, since many of these (even today) are azo dyes made from anilines (see 17.3.). In the 1860s these dye products kickstarted the organic chemical industry, and the foundation of companies such as BASF (Badische Anilin- und SodaFabrik), which now employs over 100,000 people worldwide.

One interesting feature of this reaction is that we are converting an electron-withdrawing NO2 group to an electron-donating NH2 group; as we will learn in section 14.3, this affects the reactivity of the ring significantly. In designing a synthesis of an aromatic amine, we may choose to delay the reduction step in order to take advantage of the meta-directing effect of the nitro group first. This is discussed further in section 14.4. Another aspect we need to consider is that the reducing agent we use may also cause the reduction of other functional groups; for example, H2/Pd on C will also reduce alkenes to alkanes (see 19.4.) and this may affect our choice of reagent. One common reducing agent, sodium borohydride (NaBH4), does not reduce aromatic nitro compounds under standard conditions, so that may be used for many reductions where the NO2 needs to be left intact.

Below are two typical examples of nitro reductions:

Khan Academy videos

References

- Laali, Kenneth K., and Volkar J. Gettwert. “Electrophilic Nitration of Aromatics in Ionic Liquid Solvents.” The Journal of Organic Chemistry 66 (Dec. 2000): 35-40. American Chemical Society.

- Malhotra, Ripudaman, Subhash C. Narang, and George A. Olah. Nitration: Methods and Mechanisms. New York: VCH Publishers, Inc., 1989.

- Sauls, Thomas W., Walter H. Rueggeberg, and Samuel L. Norwood. “On the Mechanism of Sulfonation of the Aromatic Nucleus and Sulfone Formation.” The Journal of Organic Chemistry 66 (1955): 455-465. American Chemical Society.

- Vollhardt, Peter. Organic Chemistry : Structure and Function. 5th ed. Boston: W. H. Freeman & Company, 2007.

Contributors

- Prof. Steven Farmer (Sonoma State University)

- William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry

Contributors

- Dr. Dietmar Kennepohl FCIC (Professor of Chemistry, Athabasca University)

- Prof. Steven Farmer (Sonoma State University)

- Catherine Nguyen

- William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry

Contributors

- Dr. Dietmar Kennepohl FCIC (Professor of Chemistry, Athabasca University)

- Prof. Steven Farmer (Sonoma State University)

- William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry

- Mario Morataya (UCD)

- Gamini Gunawardena from the OChemPal site (Utah Valley University)

Candela Citations

- 18.2: The General Mechanism. Authored by: Prof. Steven Farmer, William Reusch, Professor Emeritus . Provided by: Sonoma State University, Michigan State U. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Smith)/Chapter_18%3A_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution/18.2%3A_The_General_Mechanism. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts . License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Synthesis of Benzene Derivatives: Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution. Authored by: Steve Maxwell. Provided by: UCD. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_(Organic_Chemistry)/Arenes/Synthesis_of_Arenes/Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 16.1: Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions - Bromination. Authored by: Dr. Dietmar Kennepohl FCIC; Prof. Steven Farmer; Catherine Nguyen; Wiliam Reusch, Professor Emeritus. Provided by: Athabasca University; Sonoma State University; Michigan State U. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(McMurry)/Chapter_16%3A_Chemistry_of_Benzene_-_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution/16.01_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution_Reactions%3A_Bromination. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 18.4: Nitration and Sulfonation. Authored by: Anonymous. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Smith)/Chapter_18%3A_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution/18.4%3A_Nitration_and_Sulfonation. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 16.10 Reduction of Aromatic Compounds. Authored by: Dr. Dietmar Kennepohl FCIC; Prof. Steven Farmer; William Reusch, Professor Emeritus; Mario Morataya; Gamini Gunawardena . Provided by: Athabasca University; Sonoma State University; Michigan State U; UCD; Utah Valley University. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/LibreTexts/Athabasca_University/Chemistry_350%3A_Organic_Chemistry_I/Chapter_16%3A_Chemistry_of_Benzene%3A_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution/16.10_Reduction_of_Aromatic_Compounds. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike